Great Britain began the war in 1939 with a fleet of 57 submarines, the exact same number as the Germans. The Royal Navy produced quite a large number of different classes of boats but three would be most prominent; the S, T, and U-class boats of which the most famous is probably the "T-class".

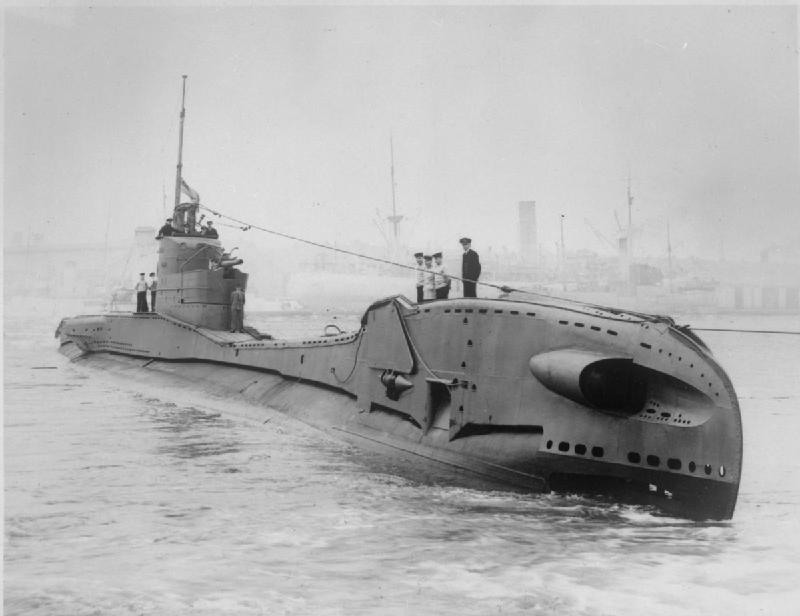

A "T-Class" british submarine: the "HMS Thorn"

Like the Italians, who had a very large submarine force (more than one hundred in summer 1940: 115 in total, of which only 84 were operational), the British opted for reliability rather than innovation. For instance, like the Italians, they stuck to the old-fashioned impact fuse for their torpedoes rather than the more sophisticated magnetic fuses used by the Germans and Americans. This made them less effective but, unlike both Germany and America, Britain did not have to go through a period of having unreliable or totally faulty weapons while the bugs were worked out of this new technology. Rather, the British compensated for the weaker destructive power of the impact fuses (in which the brunt of the explosion is focused away from the target) by having boats that packed a larger punch than those of any other navy.

British "T-class" submarines were the best and were built to fire an astonishing 10 torpedoes at a time which, British naval engineers reasoned, would more than make up for the drawbacks of their fuses as well as the less advanced targeting systems of British boats. If ten torpedoes are fired at a single target, one or more will almost have to hit it.

British submarine success was to be found mainly in the waters of the Mediterranean Sea, where British submarines would have their biggest impact on the world war two.

The largest threat, obviously, was the powerful Italian navy and the extensive coverage over the Mediterranean by the Italian air force. However, due to the shortage of fuel and their industrial inability to keep up with any significant rate of attrition, the Italian surface navy would be forced to remain on the defensive.

British "T-class" submarines began to operate in the Mediterranean from September 1940 onward. This was the theatre in which the T class were most heavily engaged in operations and correspondingly suffered proportionately heavy losses.

Operations in the Mediterranean posed several substantial challenges for British submarines and the T class in particular. Firstly, the Italian Regia Marina, almost uniquely among the Axis navies, had devoted a substantial amount of resources and training to anti-submarine warfare. Equipped with their own version of sonar, the ecogoniometro (ECG), possessing excellent escort vessels, and making extensive use of mines, the Italians were to prove the most successful of the Axis powers at destroying Allied submarines.

Indeed in the Mediterranean, Italian submarines during WW2 sank 21 merchantmen and 13 enemy warships for a total of more than 100,000 tons; in addition, they were often used for carrying the crews and human torpedoes (nicknamed "Maiali") of the "Decima Flottiglia MAS" (which sank warships totalling 78,000 tons and 20 merchant ships totalling 130,000 tons).

History during WW2

The first British submarine success in the Mediterranean was, due to confusion over their status, the sinking of a French sloop. While screening a convoy, the submarine "HMS Phoenix" spotted the main Italian fleet, leading to a fairly significant engagement, but the Phoenix was then sunk by an Italian torpedo boat on July 16, 1940. On the final day of the July month, "HMS Oswald" was sunk by an Italian destroyer off the coast of Messina. As the Germans had done in the North Sea, Italian shore installations used radio direction-finding (the "idrofono") to locate the British submarine and the Italian destroyers then moved in for the kill (read with google translator from Italian: https://www.ocean4future.org/savetheocean/archives/35220).

Morale fell as British submarine losses continued and though successes did increase when the government in London authorized the use of unrestricted submarine warfare, the latter half of 1940 was fairly disastrous for the Royal Navy boats.

While sinking less than 1% of Italian shipping to North Africa, Britain had lost nine submarines, five at the hands of the Italian navy and the rest to air attack or mines. At one point, Britain was reduced to only five operational submarines in the full Mediterranean!

Clearly, something had to be done. Italian shipping losses had been extremely light in 1940, warships were not engaged and overall Italian superiority in the central Mediterranean had been maintained.

It was a gloomy time as the British came to grips with the fact that, despite what Allied propaganda had told them, their enemy was a formidable one.

Photo of the Italian "torpediniera Pegaso", that on 6 August 1942 destroyed with deep charges the British submarine HMS Thorn. This torpedo boat was one of the most successful AXIS anti-submarine warships of World War II. It never surrendered to the Allies, preferring to do a scuttling in Spanish Minorca island on 09/09/1943

However, the British did what they have traditionally done; learned from their mistakes and adapted.

As with the Germans (or the Japanese for that matter), Italian underwater detection gear was not good. The British knew this and so finally came to appreciate that, other than aircraft, the primary way their boats were being located was by radio direction-finding.

The British responded by ordering their subs to maintain radio silence unless communication was absolutely necessary. The British also ultimately adopted the practice of keeping their boats submerged throughout the daylight hours if at all possible, only surfacing at night. This reduced their mobility of course but also made them much less likely to be detected by lookouts on ship or shore or by patrolling Italian aircraft.

The Admiralty also sent many more submarines to Malta such as 10 new U-class boats in early 1941. With a greater respect for their enemy, more care given to stealth and increased use of mines, British successes began to pick up. In February of 1941 "HMS Upright" attacked and sank the Italian cruiser "Armando Diaz" in a surface attack at night, the biggest victory British submarines had yet had in the Mediterranean.

In March 1941, "HMS Rorqual" laid a minefield, sent two freighters to the bottom and then sank the Italian submarine "Capponi". The same month, another British boat, the "P31", made a successful attack on a large freighter using Asdic (sonar) alone, earning the commander the DSO.

The following month also saw the beginning of a string of victories for the man who would be the most successful British submarine commander of World War II, Lt. Comm. Malcolm D. Wanklyn of "HMS Upholder". He sank a freighter in April off Tunisia and two more on May 1, beginning what would be a very successful career, albeit a short one. Sadly, Wanklyn was killed in action in 1942 by the Italian navy but by that time had managed to sink 21 Axis vessels, earning the Victoria Cross.

Because of men like him, things were turning around for the British war under the waves. In the first half of 1941 they managed to sink about 130,000 tons of Axis shipping while losing only two submarines, both to Italian minefields. Still, the rate of success was slow at less than two ships a month. Furthermore, of the shipping interdicted by the Allies, including the movement of Rommel’s Afrika Korps to Libya, less than 5% was lost to British submarines.

However, the British were steadily improving and were aided by two significant events:1) the invasion of the Soviet Union, which meant the redeployment of enemy air forces and 2) the breaking of Axis codes, which allowed the British to have up to date information on Italian naval movements.

The British also very cleverly took care to move aircraft into the area of Italian convoys before the submarines arrived to make their attack so that the Axis high command would assume the RAF had spotted their ships and not catch on to the fact that their codes had been broken. This allowed for more British submarines successes going forward.

In September of 1941 the boats at Malta were organized into the Tenth Submarine Flotilla and the “Fighting Tenth” would prove the most successful British submarine force of the war, though also the one with the highest casualty rate.

Having inside information (from Italian antifascist organizations) on when and wear Italian supply convoys would be sailing, the British were able to post their submarines in picket lines in front of the enemy.

In so doing, the British boats began to really bite into the Axis war effort, sinking four Italian troopships (with some hundreds of Italian soldiers killed) in a few weeks and badly damaging the new Italian battleship "Vittorio Veneto", which was attacked by "HMS Urge" and put out of action for over three months.

In the second half of 1941 the British lost six submarines but received 13 new boats and, in that time, managed to take a significant toll on Axis shipping (which was critical to the North African war effort). In the desert, logistics were paramount and when the supplies flowed, Rommel advanced; when they did not, the Italo-German forces fell back.

The losses were serious enough to compel the Germans to dispatch some of their own U-boats to the Mediterranean, adding a new and dangerous foe for the British to deal with: proven when the German "U-81" managed to sink the only British aircraft carrier in the Mediterranean, "HMS Ark Royal", in November 1941.

Moreover, German and Italian air attacks on Malta proved to be devastating, eventually wiping out the RAF defenders, forcing the withdrawal of many ships and damaging three submarines.

Nonetheless, the British boats continued to put up a terrific fight with "HMS Upholder" sinking the Italian submarine "St Bon" in January of 1942 and "HMS Unbeaten" sinking the German submarine "U-374" not long after. In March 1942 the "Upholder" sent another Italian submarine, the "Tricheco", to the bottom off Brindisi.

However, the Germans had developed better detection gear and shared this with the Italians to great effect. The Italian torpedo boat "Circe" took out two British submarines using the new gear.

The Italians also made ever greater use of minefields and this, combined with the sinking of the British minesweepers, ultimately made Malta untenable as a naval base. The island was ripe for the picking, however, it was saved by German Field Marshal Rommel who convinced the high command to call off the invasion in favor of his attack into Egypt. At one point only 12 British submarines were on hand in the area and the Royal Navy was more stretched than ever with the Empire of Japan now menacing the British Empire in the Far East. Many of the boats previously stationed in Malta had been transferred from Asia, which was now also under attack.

Dogged determination proved effective though and despite the reduction in numbers in April of 1942, British submarines sank 117,000 tons of Axis shipping along with the Italian cruiser "Bande Nere" (sunk by "HMS Urge"), a destroyer and six Axis submarines. It amounted to only 6% of the materials being sent to Rommel in North Africa but, due to the withdrawal from Malta, was significantly more than what the RAF had managed to intercept.

British submarines were also being used to carry cargo to keep Malta alive as Italian naval forces prevented much of the surface convoys from landing their supplies. To fight back against this, British submarines were dispatched to prowl outside the main anchorages of the Italian fleet, to attack when possible but also to warn the high command of when they were moving out. The result was a fierce fight for control of the Central Mediterranean with wins and losses for both sides.

However, the need for Axis air power on the Russian front gave the British some breathing room and soon more and more Royal Navy subs were posted to the Mediterranean with new flotillas organized in Gibraltar and Beirut.

The British war effort was also aided by the fact that the increasingly critical fuel shortages meant that the main Italian battlefield was forced to stay in port most of the time.

This, combined with the determination of British air and naval forces, meant that Malta was able to be built back up and more Axis shipping to North Africa was sunk.

In October of 1942, even while preparing for the invasion of French North Africa, British submarines still sank 12 enemy ships and one destroyer. When the Axis powers began moving men and supplies into Tunsia to counter the arrival of the Americans, British submarines accounted for 16 ships lost while the RAF took out even more.

Their actions were making it ever more difficult for the Axis forces in North Africa to be maintained much less take offensive action. By 1943 the Gibraltar flotilla moved to Algeria, Allied air power dominated the Mediterranean and the Axis shipping lanes were devastated with British submarines accounting for 33 Axis ships. I

n early 1943 the subs destroyed more ships at sea than any other force, surpassed only by Allied aircraft whose successes included ships in port.

Axis power was receding in the Mediterranean and the British boats were at the forefront of the naval victory thanks to men like Comm. J. W. Linton of "HMS Turbulent" who was killed in action after sinking 90,000 tons of enemy shipping and an Italian destroyer. He was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross.

Comm. George Hunt of "HMS Ultor" sank more Axis ships than any other British submarine commander at 30 for which he earned the DSO with bar twice. Comm. Ben Bryant was similarly decorated for sinking over 20 Axis vessels as well as numerous warships.

With the capture of Sicily by the Allies, the naval war was practically over but, while outpaced by the air forces, Allied submarines, mostly British, accounted for roughly half of all Axis naval losses in the Mediterranean.

Overall, the British submarine force made a significant contribution to the defeat of Germany, Italy and Japan. Early on, they suffered some serious losses and learned some hard lessons against the Germans in the North Sea and the Italians in the Mediterranean.

However, they adapted and came roaring back, taking a considerable toll on Axis warships and plaguing the supply lines keeping Rommel and his Italo-German forces in the field in North Africa. One of, if not the most decisive factor in the successful British defense of Egypt was Rommel’s lack of sufficient fuel and supplies and the British submarine force played a major part in that.

Photo of the "Leonardo Da Vinci", the most successful Italian submarine in World War II, that sunk 121000 tons of Allied ships and was going to be prepared to attack New York port in summer 1943. But this submarine was sunk on 23 May 1943 by the escorts of British convoy KMF 15. There were no survivors. Leonardo da Vinci was the top scoring non-German submarine of the entire war. (read my: https://researchomnia.blogspot.com/2025/10/tentatives-of-italian-attacks-over-new.html )

In 1943 at Italy's surrender the "Regia Marina" had only 34 submarines operational, having lost 92 vessels in action (over two-thirds of their number), while 3,021 men of the Italian submarine service were lost at sea during the war.

a large num

ber of different classes of boats but three would be most prominent; the S, T, and U-class boats of which the most famous is probably the T-class. Like the Italians, who had a very large submarine force, the British opted for reliability rather than innovation. For instance, like the Italians, they stuck to the old-fashioned impact fuse for their torpedoes rather than the more sophisticated magnetic fuses used by the Germans and Americans. This made them less effective but, unlike both Germany and America, Britain did not have to go through a period of having unreliable or totally faulty weapons while the bugs were worked out of this new technology. Rather, the British compensated for the weaker destructive power of the impact fuses (in which the brunt of the explosion is focused away from the target) by having boats that packed a larger punch than those of any other navy. British T-class submarines were built to fire an astonishing 10 torpedoes at a time which, British naval engineers reasoned, would more than make up for the drawbacks of their fuses as well as the less advanced targeting systems of British boats. If ten torpedoes are fired at a single target, one or more will almost have to hit it.

No comments:

Post a Comment