This month I am going to translate two articles appeared on the website "Unione degli Istriani" about the ethnic clearance of the autochthonous Italians in Istria & Dalmatia, done by the Slav population (living in these regions) during the first half of the XX century.

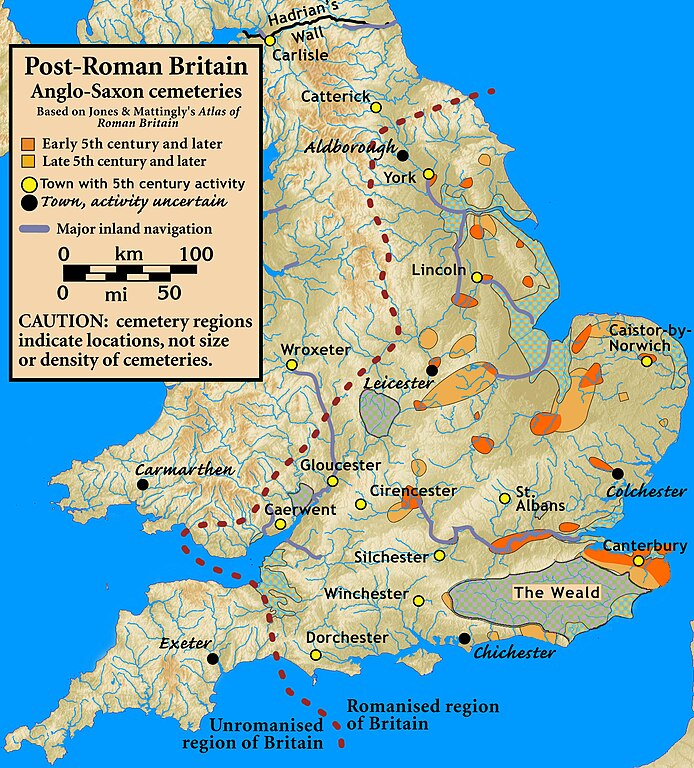

Istria -with the Quarnaro islands- when was inside the Kingdom of Italy, between 1918 and 1947

We all know that there has been continuously attacks of every kind against the survival of the original Latin populations in the eastern coastal Adriatic sea, since the end of the Republic of Venice until after the Second World War. Actually there it is a kind of "campaign" to deny this ethnic "clearance" and for this reason I want to publish these two articles (one about Dalmatia and the second about Istria).

Here it is the first (after my introduction):

INTRODUCTION

Until the beginning of 1920 the Italians of Spalato (now called Split, the main Dalmatia's city) never attacked the Slavs (even because of obvious numerical inferiority) and were harassed by Croatian nationalists continuously, as has happened since the last decades of the XIX century in all Dalmatia.

But after the attack of January 27, 1920 in which were damaged nearly all the Italian-owned shops and the offices of Italian institutions, some Italian sailors of the Italian navy ship "Puglia" now under the command of captain Tommaso Gulli and docked inside the Spalato's port, started to defend themselves and the Dalmatian Italians while menacing to use their guns.

On July 27 another attack against the Italians of Spalato was done and a group of officials of this "Puglia" found refuge in a place near the docks: captain Gulli ordered a boat to rescue them, but it was blocked by some Slavs and was forced to fire "alarm shots" in the sky to get help.

Soon Gulli went to the rescue with a MAS torpedo-boat, but approaching the docks found a huge crowd of nationalist Slavs. Shots were fired to the Italians and for the first time they returned fire. A hand granade was thrown to the Mas and hit the sailor Aldo Rossi and others.

Another shot hit captain Gulli, while the Italians killed a man on the docks, whose name was Matej Mis. Anyway, many versions about what happened were done in the next days, by the Yugoslavians and by the Italians.

Captain Gulli was helped in a Hospital but died the next day, while sailor Rossi survived only a few hours.

In the Kingdom of Italy the reaction to what happened in Spalato was of rage and indignation: in Trieste fascists and nationalists attacked the Hotel Balkan (called in Slovenian "Narodni dom" and center of all the Slav activities & attacks in Trieste) the next day.

In the following years the Italians of Spalato - under the Yugoslavian rule renamed "Split", as was officially called the city since 1919- were continuously harassed in their institutions, schools and shops & business: they declined in their amount in a slow but steady way.

At the end of the 1920s, relations between Italy and Yugoslavia worsened again, and the Croatian Split press called on the population to boycott the italian shops. One of these shops was the Del Bianco barber shop, since "... the owner is an open and great "Italianizer"..... let us remember that our "Italianizers" are for us greater enemies than true Italians". In the attacks on Italian shops in Spalato in May 1928, the Del Bianco barber shop inside the Peristyle of Diocletian's Palace was destroyed and the owner forced to get refuge in Italy. The above quotations are taken from the daily newspaper Pobeda of 9 March 1928,

Actually the "Spalatini" (as care called the autochthonous Italians of Spalato) are only one hundred in Croatian Split, with their association called Comunitá italiana di Spalato. They were more than 2,082 in the 1910 city census but were nearly seven thousand in 1918, including the surroundings! And from Roman centuries until the end of the Napoleon's rule of Dalmatia they were the majority of the Spalato population (they were approximately 2/3 of all the dalmatian city's inhabitants in 1815).

UNIONE DEGLI ISTRIANI

1930: ITALIANS SUFFERED A "POGROM" IN DALMATIA (THE “POGROM” OF THE ITALIANS OF SPLIT AND SEBENICO THAT NO ONE EVER TALKS ABOUT)

Photo of Spalato (now called Split in Croatia) in the early 1930s Dalmatia of Yugoslavia

Dear Friends,

we want to remember what happened in Spalato on the night between 18 and 19 October 1930, or what we could call the "pogrom" against the Italians living in the largest city in Dalmatia, a pogrom that continues to remain a taboo. It happened, that night ninety-five years ago, that all the Italian businesses in the city were marked with crosses and writings made with the use of black tar, almost impossible to erase, of the following tenor:

"THIS SHOP IS ITALIAN. DO NOT ENTER!"

The action of that night was the final act of a long persecutory campaign against everything Italian in Yugoslavia and at the same time the start of a massive boycott of Italian merchants and industrialists who, in fact, were forced in a few years to close practically all their businesses.

In Spalato, however, the smear campaign had already begun in January 1930: the city newspaper "Zastava", directed by the fierce enemy of the Italians, the nationalist Oskar Tartalja, gave daily news of Italian public establishments, companies and professionals, under the pretext of making a numerical comparison of the two elements, Italian and Slav.

On January 1, 1931, after the "pogrom", the physical attacks, the destruction of shop windows and the looting of several shops, with the consequent first departures of our totally defenseless compatriots, the daily newspaper ran a full-page admonitory headline "Let's give Split a national character", offering the following well-listed intentions:

"It is our duty:

1) to be enemies of the enemies of our people;

2) to always and everywhere use our Yugoslav language;

3) to protect our language, our money, our men, our shopkeepers;

4) to help our people. We will not have peace until we have removed the foreign trace, until Split acquires a pure Yugoslav national character."

A proclamation, this, worthy of the worst National Socialist projects. But no one ever talks about it.

In Sebenico, however, a few days later, something more explicit, institutional happened. On October 20, 1930, in the session of the City Council, in the presence of the district captain who represented the Government of Belgrade, Councilor Lawyer Medina, former head of the city section of the secret organization Orjuna, voted on the text of the following order of the day, made immediately executable:

"the authorities should intensify in every way their action aimed at taking away every and every means of work from Italian citizens, ordering employers to fire them, denying the granting of new licenses, so as to create impossible living conditions for Italian citizens".

In the same session, Councilor Lawyer Kozul unanimously passed the proposal to erect a monument to King Peter " , replacing the one to Nicolò Tommaseo with this new monument ".

Borders and ethnicity of Istria in 1910, with actual yellow points as frontier between Italy and Slovenia. Map of the Touring Club Italiano

Here it is the second article (after my introduction):

INTRODUCTION

Istria has been a Latin populated region since Roman centuries. The Slav penetration started during the Middle Ages and happened mainly in the eastern area of the peninsula. The western half of Istria remained romance speaking (first with the Dalmatian, then with the Venetian and now with the Italian language) until the huge "Istrian-Dalmatian exodus" that happened during and after the Second World War.

This exodus started in September 1943, after the Italian surrender to the Allies, then grew with the communist Tito's massacres in Istria (the "Foibe" tragedy) and finally exploded in 1945 & following years (when nearly 350000 Italians escaped from the region that was officially annexed to Yugoslavia in 1947).

The Dalmatian city of Zara was part of the kingdom of Italy since 1918, but lost in 1944 nearly all the Italians living there: At the start of World War II, Zara had a population of 24,000; by the end of 1944, this had decreased to 6,000.Though controlled by the Partisans, Zara remained under nominal Italian sovereignty until the Paris Peace Treaties that took effect on 15 September 1947.[After the war practically all the Dalmatian Italians of Zara left Yugoslavia towards Italy: in 2021 only a dozen Italians remained in the city!.

Also the Istria's coastal city of Pola was the site of a large-scale exodus of its Italian population. Between December 1946 and September 1947, Pola almost completely emptied as its residents left all their possessions and "opted" for Italian citizenship. More than 28,000 of the city's population of 32,000 left in March/April 1947.

The last exodus happened in 1954 and took place after the "Memorandum of Understanding" in London about the Free Territory of Trieste, that gave provisional civil administration of Zone A (with Trieste) to Italy, and Zone B to Yugoslavia.

The Italians who moved out of Istria were relatively "lucky", because many thousands of them disappeared in the Foibe from 1943 until 1945. Indeed the so called "Italian Holocaust" is centered on the massacres of the Foibe, done by the Yugoslav dictator Tito and his communist Slav party.

The number of victims in the Foibe is uncertain. Historians like Raoul Pupo or Roberto Spazzali estimated the total number of victims at about 5,000; Guido Rumici and Giorgio Pisano' calculate from 11,000 upwards. It was never possible to extract all the thousands of corpses from Foibes, because some of them are deeper than several hundred meters. Until few years ago authorities had been able to extract from the pits just a small number of bodies: less than six hundred.

Last but not least, we must remember that the internationally famous historian Rummel calculated that -in addition to 24,000 italian deaths because of Foibe, lynching, hanging, drowning, summary executions by firing squads, etc...- between May 1945 and the end of 1947, more than 190,000 Italians crossed the border. And he wrote thet here were also 160,000 people, including ex-partisans and anti-fascists, who left after Stalin’s break with Tito (1948-49) or as a result of the "Trieste crisis" in 1954. The total is 350,000 refugees with 24,000 killed (of the nearly 430,000 Italians living -before 1940- in the area lost by Italy): that means that in 1954 there were only 56,000 Italians in the areas that Yugoslavia annexed. And their number is getting smaller and smaller: according to the census organized in Croatia in 2001 and the one organized in Slovenia in 2002, the Italians who remained in the former Yugoslavia amounted to 21,894 people (2,258 in Slovenia and 19,636 in Croatia).

It is noteworthy to pinpoint that this exodus was caused -by the Slavs- often with cruelty and sadism in many cases, as can be understood reading the following essay, written by a direct testimony: Nidia Cernecca.

Photo of the recovery of human remains of Italians from the Vines/Goglia Foibe, in Faraguni locality, near Albona d'Istria in October of 1943. From this sinkhole, between 16 and 25 October 1943, the human remains of 84 bodies were recovered (72 Italians, of whom 6 were women, and 12 German soldiers). Of the victims, 51 were initially recognized. In this sinkhole, some victims were thrown while still alive. The murdered were also thrown with a stone tied to their hands with wire; or tied together in such a way that a single victim hit by a gun dragged his still-alive companion tied to him to the bottom of the sinkhole. The criminal perpetrators then threw hand grenades into the Foiba, in order to cause the walls of the sinkhole to collapse, perhaps to facilitate the decomposition of the bodies, thus making their eventual subsequent recognition impossible. The victims were extracted with huge difficulties.The discovery of this Foiba, as a place of execution and burial, is due to the report of B. Monti of Albona. The only survivors who survived from this Foiba (because screaming for help from the bottom, one day after being pushed inside by the cruel Tito's partisans) were Giovanni Radeticchio and Graziano Udovisi, who as witnesses recounted the event.

UNIONE DEGLI ISTRIANI