Many books have been written about the "Ilinden Uprising" and Macedonia's independence, but only a few study in detail the Aromanians and their interaction with Macedonian organizations.

First of all we must remember that during the summer 1903 rebellion in the region of Macedonia most of the central and southwestern parts of the Ottoman "Monastir Vilayet" were devastated by the Ottoman forces. These Turks attacked the independence fighters, who were receiving the support of the local Slav peasants with a huge help from the Aromanians (called also "Vlachs") living in the region. Provisional government was established in the town of Krusevo, where the insurgents proclaimed the "Krusevo Republic" which was overrun in a bloody way after just ten days, on August 12.

Indeed in March 1903, the Aromanian Pitu Gulli began commanding a revolutionary squad, crossing the Bulgarian-Ottoman border heading for Krusevo. From April to August 1903, he trained and prepared his irregulars for the upcoming Ilinden Uprising. He died in Kruševo, defending the Krusevo Republic with his nearly 1000 Aromanian fighters.

Many of the independence fighters in Krusevo were Aromanians: according to the ethnographer Vasil Kanchov's statistics based on linguistic affinity, at that time the town's inhabitants counted: 4,950 Slavs, more than 4,000 Vlachs (Aromanians) and 400 Orthodox Albanians.

The "prime minister" of the Krusevo republic was the Aromanian Vangel Dunu.

Mečkin Kamen (where today there it is a commemorative monument) was the place where Pitu Guli's fighters (most of them Aromanians) defended the town of Kruševo from the Turkish troops coming from Bitola. Nearly the whole squad and their leader perished during the battle. And Kruševo as well as many of the nearby villages were set to fire by the Ottomans.

However, following the revolt, Romania, with the support of Austria-Hungary and Italy, succeeded in the acceptance of Vlachs as a separate millet with the decree ("irade" in turkish) of May 22, 1905 by Sultan Abdulhamid; so in the "Ullah millet" (the millet of the Vlachs, the first "proto-state" of the Aromanians in their History) they could have their own churches and schools.

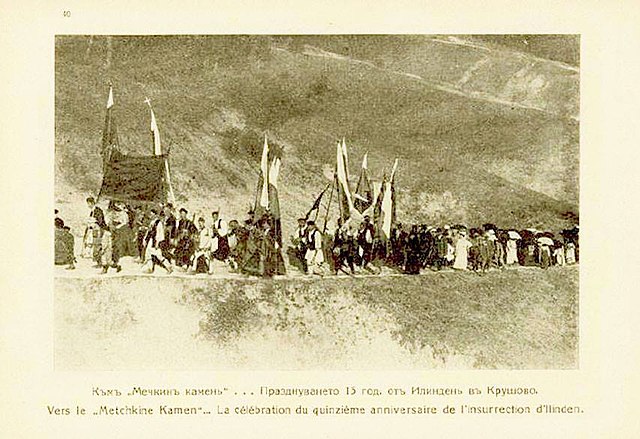

Photo showing the 2011 celebration of the "Krusevo Republic". Note the monument to the Ilinden Uprising of summer 1903.

In the following decades the Aromanian population in Krusevo has been reduced because of many reasons, but in 2020 there are -still- more than 1200 Aromanians in this macedonian city of nearly 6000 inhabitants.

THE AROMANIANS AND THE IMRO

The Macedonian revolutionary national-liberation movement, organized and led by the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO) has long provoked the interest of contemporaries and scholars of the

modern Macedonian history. The interest shown by the numerous diplomats, historians, journalists and analysts has produced an enormous historiographic work which examines IMRO and the Macedonian revolutionary

movement from every aspect.

However, the origins, acts and goals of IMRO can naturally be viewed differently, taking into account each author’s

provenance and the time at which the work was published.

The same can be

said for the Aromanian participation in the revolutionary organization.

While historians in the Republic of Macedonia and Bulgaria acknowledge the

Aromanian contribution within IMRO, the two sides who have traditionally

invested the most interest in the Aromanian question – Romania and Greece – have preferred either to ignore the Macedo-Aromanian collaboration,

or to present the Aromanian involvement in the Organization as “forced collaboration”, under pressure from the “Bulgarian bandits”.

This stance has its roots in Romania and Greece’s Macedonian policy from the end of the 19th

and the beginning of the 20th century. The Romanian propagandistic presence in Macedonia focuses on the Aromanian population, presenting them

as being part of the Romanian nation. On the one side, the future existence

of this propaganda in Macedonia required the Aromanians – seen as Romania’s pawn on the Balkan chess table – to remain faithful subjects of the

Sultan. On the other side, Bucharest did not want to see (or simply could not see) IMRO’s indigenousness, and no matter how much IMRO kept

proving its independence from the Bulgarian cabinet, Romanians considered the Macedonian revolutionary movement to be spurious, fostered by

Sofia, and in it the Romanian politicians saw nothing else but an extended

arm of Bulgaria’s expansionistic policy.

For this reason Aromanian participation in IMRO complicated Romania’s position, not only for the fear that

Bulgaria would steal Bucharest’s main trump card in its Macedonian policy,

but also due to the realistic danger of disturbing amicable relations with the

Ottoman Empire.

The Greek Kingdom also had important plans with the

Latin speaking people north of its border, and for this it gave the Aromanians a vital role in the Great Idea’s fulfillment. Greece had little to worry

about while the various nationalities in the Ottoman Empire were under the

jurisdiction of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, but when the

Slavic population of Macedonia joined the Exarchate en masse, the number

of “Greeks” in Macedonia started its uncontrollable decrease.

Were the

Aromanians to follow the same example, then it is likely that Hellenism

would have to completely vanish from a number of cities in Macedonia,

whose presence was principally represented by the Aromanian population.

If the Aromanians were shown to be Greeks, then Greece could claim to

have citizens north in Bitola and Krushevo. If, on the other hand, the Aromanians were not considered to be Greeks, then Greece’s claims in Macedonia were seriously threatened, with only a negligible minority living more

than 100 kilometers north of its border. Hellenism would be forced to retreat south of the river Bistritsa (Haliacmon) and the Greeks would cut a poor

figure among the statistics of the Macedonian races. The Aromanians were

Greece’s predetermined prize and Athens could not let them fall in the

hands of its arch enemy in Macedonia, the Bulgarians.

This line of thinking was the main reason for the numerous statements given by Romanian and Greek diplomats, distributed to the public in

both countries through pro-governmental media, in which they deny the

Aromanian involvement in IMRO and the Ilinden Uprising. Whenever the

Aromanian presence in the revolutionary bands was confirmed by the Ottoman authorities, Bucharest and Athens found a convenient excuse, claiming

that the Aromanians were subjects of atrocities committed by the “Bulgarian

bands” and that they were forced to join IMRO. This is the reason for which

the Greek consul in Bitola, Kypreos, claims that the Aromanian settlements were under strong pressure from the

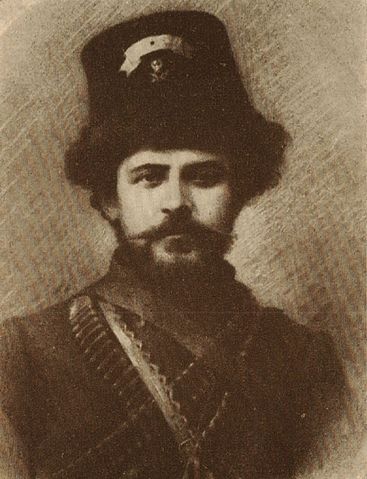

Photo of the squad of aromanian leader Pitu Guli near Birino, in 1903

The pro - governmental media in the Romanian capital came

out with similar statements that “the Romanians from Macedonia did not take part

in the Bulgarian revolutionary movement, nor did they sympathize with it, and when they

did take part, they were doing so because they were forced by the Bulgarian bands” . It

was claimed that “The Romanians endure the consequences from the bitter war between

the bands of the committees and the Turkish army. The Romanian settlements are occupied due to strategical or other motives and forced to… give youngsters to the bands”. Certain Romanian newspapers were informing the public how those killed

in the Ilinden Uprising in Krushevo were mostly “Romanians who became victims of a battle with which they have nothing in common, while the insurgents were

described as pseudo-liberators and “Bulgarian bands who killed most of the Romanians who refused to support the rebellion”.

Not many were willing to deny the claims coming from the political

circles in Athens and Bucharest, with certain notable exceptions. Those

who were most informed about the Aromanian involvement in the Organization and in the Ilinden uprising, i.e the leaders and the members of IMRO, preferred not to talk about it in order to protect the Aromanian villages

from the regular Ottoman army and the bashi - bazouks.

In the few historical studies that deal with the Aromanian presence

in IMRO, it is indicated that the main reason which attracted the Aromanians to join the Organization were “the terrible cruelties and injustices committed

over them by the Ottoman authorities”. This claim is correct in principle, but it is

too simplified and only partially explains why the Aromanians showed solidarity with the Macedonian revolutionaries.

The rationale behind why one

part of the Aromanian population accepted IMRO, one part showed indifference and the third part refused any sort of cooperation, therefore openly

showing its animosity towards the Organization, is much more complex and

requires more space for analysis.

We do not aspire to write a complete analysis of the Aromanian involvement and influence in IMRO, so we will limit the inquiry to the reasons which resulted in a part of the Aromanian population joining the Macedonian Revolutionary Organization.

A large number of Aromanian and Megleno-Vlach villages did indeed feel the weight of the Ottoman yoke. The terror inflicted by the Ottomans and the nearby Islamized village of Nonte was felt the most by the

Megleno-Vlachs. When the German linguist Gustav Weigand visited Meglen in 1890, the first thing he noticed was the horrible poverty, atypical for

the Aromanian villages he had previously visited. The village of Birislav was

a chiflik of Nonte and the villagers were regularly terrorized by their masters and by the soldiers. Oshin, Luguntsi and Huma were properties belonging to Turks and Jews from Salonica, while the Aromanian village of Livadi was chiflik of Turkish beys from Yannitsa. Most of the other MeglenoVlach villages were also chifliks.

Relatively isolated and yet situated in an excellent strategic position near the main road that led to Salonica, under

strong influence from their Slavic neighbors and with little to no Greek influence among them, the Megleno-Vlach villages quickly attracted the attention of IMRO’s leaders. The first article of IMRO’s constitution from

1897, which allowed all unsatisfied element of the population in Macedonia

and Odrin to be included in the Organization regardless of ethnicity, widely opened IMRO’s doors for the non-Slavic population in Meglen. Argir

Manasiev and Vasil Chekalarov set up the organizational foundation in Barovitsa and in 1897 the same two visited many villages on Mount Pajak

(Paiko) after which IMRO’s ideas finally reached the Megleno-Vlachs. Manasiev’s tremendous organizational qualities soon bore their fruit. According to one of IMRO’s leaders in the Gevgeli region, Sava Mihajlov, all the

Vlach villages in the Gevgeli area were faithful to the Organization. The

number of IMRO band leaders (voivods), corporals and normal band members emerging from the villages in Vlacho-Meglen was impressive. The

huts of the Aromanian nomads from Livadi and the Vlach huts on mount

Kozhuf were regularly used as shelters by IMRO’s bands.

The living conditions of the Aromanians in kaza Kastoria were not

too dissimilar to those in Vlacho-Meglen. It is enough to read Vasil Chekalarov’s diary to confirm the Aromanian presence in Koreshtata and Nestram (Kastoria region) and the participation of the Aromanians from this

area in the revolutionary battles. Few in numbers, some comprised of five,

others of ten or fifteen houses in a particular village, the life of these Aromanians was no different than the life of their Macedonian neighbors. They

attended the same schools, went to the same churches and suffered the same torments. The coexistence and sharing of mutual problems produced a

trust between the two cultures, to the point where the IMRO makes no distinction between the Macedonians and the Aromanians in the Kastoria region, the latter being included in IMRO’s lines since its early beginnings in

this area.

If the researcher carefully follows the memoirs of the IMRO leaders

and the historical documentation of the time, they will notice that apart

from the Megleno-Vlach and Aromanian villages in Gevgeli, Yannitsa and

Kastoria, the Aromanians who were most open to IMRO were those living

in the Krushevo and Bitola regions.

Photo of Aromanian leader Pitu Guli, killed in the Ilinden Uprising defending the Krusevo republic

What pushed these Aromanians from

western Macedonia towards the Organization partially differentiates from

the events which forced the villagers from Vlacho-Meglen, Koreshtata and

Nestram to join the revolutionary battle. Granted, the living conditions in

Krushevo and Aromanian villages near Bitola were far from ideal. These

Aromanians were feeling the Ottoman pressure as well. However, issues of

a different nature strongly contributed to speeding up their access to IMRO.

Divided into pro-Greeks and pro-Romanians, the Aromanians from the

Krushevo and Bitola regions started a period of hostility long before IMRO’s appearance. Organically weaker, without its own religious hierarchy,

far from the state - protector and with no greater illusions to being liberated

by a force outside the Ottoman Empire, the pro-Romanian group was forced to seek an ally for their educational-religious battles. The only natural

partner for these Aromanians were the Macedonians and the Exarchate.

The same religious allegiance of the Macedonian exarchists and the Aromanians who accepted the religious jurisdiction of the Bulgarian Exarch, as

well as the mutual enemy – Greek propaganda – increased the mutual trust

of these two elements and facilitated the approach of the so called “romanized Aromanians” in IMRO. It was not a mere coincidence that most of the

Aromanians in IMRO were former students of the Romanian educational

institutions of the Ottoman Empire.

Unlike their compatriots from Krushevo, Bitola, Kastoria and Meglen, the Aromanians from other parts of Macedonia rarely approached the

Organization. Although the Aromanian population from Ohrid, Struga, Lerin, Resen and Kajlari was oppressed in the same manner as their fellow

countrymen from the above mentioned areas, IMRO did not manage to attract the same great number of these Aromanians. The probable explanation for this lack of success should be sought in the weaker organizational

qualities of IMRO’s activists who were operating in these zones. As in the

case of the Aromanians from other regions in Macedonia, the majority of

the Aromanians in IMRO from Ohrid, Blatsa, Pisoderi, Neveska, Resen etc

were exarchists or “romanized”.

A different and more specific category of Aromanian collaborators

with IMRO were the Aromanian nomads. These endogamous communities,

organized in a kinship-based shepherd community (taifa) and headed by the

wealthiest and most authoritative member (chelnik), lived on the mountains,

together with their large flocks of sheep. Those same mountains were regularly visited by outlaws, for which the Aromanian huts were the most natural shelter from the authorities and the inclement weather. Refusing to grant

hospitality was not an option: the shepherds could have been killed, while

the flocks, their only property, could be destroyed. Welcoming the IMRO

bands was one of the most delicate problems. To be on good terms both

with the revolutionaries and the authorities seemed highly improbable; this

is why we will accept with reserve Georgi Bazhdarov’s and Jane Sandanski’s

statements that the Aromanians from Pirin supported IMRO. Cooperation

certainly existed, but it would be incorrect to talk about certain deep beliefs

among the transhumance.

Aromanians in IMRO’s ideas, nor about the strong

wish to be liberated from Ottoman rule. The contact these Aromanian

nomads had with the authorities was minimal, and to them it did not matter who would rule the country, as long as they would be able to preserve their

traditional way of life. The cooperation between the Aromanian nomads

and IMRO can only be explained by a mutual need to help each other. The

bands needed food and shelter, while the Aromanian nomads needed IMRO’s protection from those who might steal from them.

Another form of cooperation between IMRO and the Aromanians

was the supply of weapons to bands in west Macedonia, regularly conducted

by Aromanians. Experienced merchants and muleteers, harmless nomads

and fluent Greek speakers, the Aromanians were the most natural choice to

supply the western Macedonian regions with weapons from Greece. In kaza

Kastoria the arms trafficking was conducted by the Aromanians Hristo

Gyamov, Nako Doykov, brothers Todor and Kicio Levenda from Kastoria,

brothers Ioryi and Mitre Bijov from Hrupishta, Vasil Mitrov and Ioryi

Vasilev from Smrdesh and Naum Pangiaru from Konomladi.28 The guns in

Krushevo were transported from Greece by the local Aromanians: Cola

Boiagi, Tega Hertu, Petre Pare, Vanghiu Beluvce, Vanghiu Makshut, Tachi

Liapu and Tachi Ashlak, as well as Zisi Mihali, Steriu Tanas, Steriu Taho

and Andrea Kendro from Trnovo (near Bitola).

In some cases these gun

smugglers were devoted workers of the Organization. Some of them, though, worked strictly for profit. However, we will emphasize what the Lerin

regional voivod Mihail Chekov said about the Aromanian “smugglers”. After

the disastrous ending of the Ilinden Uprising, Chekov paid two Turkish lira

to three Aromanian nomads from Blatsa to take him over the Greco-Turkish border. After numerous vicissitudes, when the voivod had been at times

dressed in female clothes, hidden among the horses and presented as their

shepherd, the three Aromanians successfully transported Chekov to Greece.

Impressed by the risk taken by his saviors, the voivod said: “On the road I understood that the Vlachs weren’t helping me for the two lira. They helped me because they

sympathized with us”.

IMRO could not penetrate into some Aromanian settlements until

1906. These were primarily Aromanian villages in Veria and Grevena, on

the Vermio and Pindus mountains. Despite the fact that a large number of

these Aromanians were supporters of the Romanian party which, as discussed, was not an impediment to Aromanians wishing to join IMRO, these

people lived far from the territory where the Organization operated and

they did not have an opportunity to establish closer relations with IMRO’s

leaders. Therefore, with some small exceptions, there is no data about the

level of participation of Aromanians from Veria and Grevena in the Macedonian national-liberation movement in its earlier stages.

Turkish sources

report of a battle that took place on June 14th 1903 between the Ottoman

army and a “Bulgarian band led by Oani Papa Arghir from Veria”, in which the

only casualty was “Nikola, Vlach from Selia”, but this short note remains the

only source of information about the Aromanian involvement in IMRO’s

pre-Ilinden actions in south-west Macedonia. A similar situation is recorded

in Macedonia’s south-eastern territories. According to Hristo Kuslev the entire Aromanian village Ramna (Demirhisar kaza) joined IMRO, but unfortunately he does not mention any names or give additional data.

The Ilinden Uprising and the information taken from the battlefields as to the massive Aromanian involvement in the insurrection (confirmed by the insurgents, the foreign diplomatic representatives and the Ottoman military authorities) undermined every attempt of Romanian and Greek

politicians to prove that the Aromanian presence in the revolutionary movement was insignificant, it was on an individual basis and as a result of the

pressure put on them by the “Bulgarian bandits”.

However, news arriving

from Macedonia gave a completely different picture, in which Aromanians

took part in attacking and capturing towns and villages, in the set up of the

local administration in the newly captured territories, as well as in defending

their conquered land. In Krushevo, Kastoria and Bitola, as well as the regions that did not massively rise and continued the guerilla warfare, “the

Vlachs did not only show compassion with the revolutionary struggle, but they actively took part in it ; they accepted all the difficulties and risks for achieving the common goal”.

The new post-uprising reality created excellent conditions to further

develop the collaboration between the Aromanians and IMRO. The Ilinden

Uprising and the Mürzsteg reforms gave credence to the Macedonian question internationally. For the neighboring Balkan states it was a clear signal

that in more favorable international circumstances the Macedonian question

could have been solved against their will and against their interests, hence

the change in their propagandistic policies. The educational and religious

propaganda became militaristic. Bands from Greece, Serbia and Bulgaria

were sent to Macedonia, with the clear task to defend the obtained positions

and later, if possible, to attempt and further expand them.

It was at this point that an unofficial civil war started in Macedonia. In it, the contingent of

the Aromanian population which stubbornly refused “to be Greek”, found itself under strong fire from the Greek guerilla groups. What started with

threats and orders to close the Romanian schools and return to the “Greek

flock”, ended with a horrific terror, killings on the roads, as well as the attacking of farms and burning of Aromanian villages after the Sultan recognized

the Aromanians as separate nation, Ulah Milet, with the Irade from May

1905.

Faced with extermination, the pro - Romanian faction began to arm

itself.

The first bands worked independently. Later, the Aromanian bands

worked under IMRO’s flag. The early local Aromanian bands were formed

spontaneously, as a direct consequence of the terror committed by the Greek bands. These groups suffered from a lack of coordination, and were hindered greatly by the fact that their radius of movement was far too limited,

and thus most of them could not fulfill the task for which they were formed. The first acting bands were those of Mihail Handuri from Livadi and

Hali Joga from Gramatikovo. Certain Nesho from Livadi, supported by

the nobility in the Vlacho-Meglen villages, formed a band independent from IMRO, but after a short illegal life he turned himself in to the Ottoman

authorities.

In 1906 Apostol Petkov sent his corporal Shteriu Canacheu –

Yunana with ten Aromanian fighters to cruise the Megleno-Vlach villages

and protect them but, influenced by the “Aromanian agitators” and the Romanian propagandists, Yunana soon became a separatist. The voivod from Livadi did not act independently for too long, soon returning to IMRO, and

in 1907 he was appointed regional band leader in the Kriva Palanka area,

leading a band of 13 fighters. The pro-Romanian group in Krushevo tried

to separate from IMRO as well, and to form an independent band led by

Vanciu Gione, but were not even allowed to start the

Preparations since their plan would have further decomposed the

front against the various foreign propaganda in Macedonia.

According to the Ottoman authorities, in 1907 there were four Aromanian bands in Macedonia fighting against the Greek bands.

Photo of the 1918 celebration of the Ilinden Uprising

Indeed on July

26th 1903 the Romanian consul in Bitola, Alexandru Padeanu, informed his

superiors that the Aromanians from Jankovec, Resen, Gopesh, Magarevo,

Trnovo and Krushevo were sick of the terror from the Turkish bashi-bazouks, and that they had armed themselves and voluntarily joined the “Bulgarian bandits”. During the Ilinden Uprising, the Greek consul in Bitola, Kypreos, reported that “the Vlahophones” took part in the uprising because they

wanted to live in freedom, not because the uprising is Bulgarian.

It is with

these words from the Greek consul that we can see the principle idea that

attracted so many Aromanians to IMRO, and we can see the clearest proof

that the Aromanians did voluntarily join the Organization.

.png/1024px-Bulgarian_national_revolutionary_movement_in_Macedonia_and_East_Thrace_(1893-1912).png)