The Romans brought in the southern coast of Finland -along an influx of imported iron (and other material) items- artifacts like Roman wine glasses and dippers as well as various coins of the Empire. During this period the (proto) Finnish culture stabilized on the coastal regions and larger graveyards become commonplace. The prosperity of the Finns rose to the level that the vast majority of gold treasures found within Finland date back to this period.

The Roman merchants probably introduced the first elementary agriculture in southern coastal Finland: at the moment, the earliest remains of ploughed fields in Finland are in the village of Salo in Laitila. According to Birgitta Roeck-Hansen and Aino Nissinaho, the dating is between ca. 330–450 AD.

Map showing the southern coast of Finland (in yellow color), where the Roman merchants traded between the first and fourth century AD. Map showing the southern coast of Finland (in yellow color), where the Roman merchants traded between the first and fourth century AD. |

Historical basckground

In Finland, the earliest finds of imported iron blades and locally processed iron objects date from around 500 BC. From around 50 BC there are indications of more intense exchange of goods from the coastal areas with areas far from the country (like the Roman Empire). The inhabitants traded their local products, probably things such as weapons for the arms and jewelery with people from the Baltic and Scandinavia as well as with people who lived along the original eastern Roman trade routes. The existence of tombs with many special objects, especially weapons, suggests that there was a ruling group of chiefs to the south and west of the country. Elevated castles spread throughout most of southern Finland at the end of the Iron Age and early Middle Ages. There is now widely accepted evidence of early state formation from that period, and there is no doubt that actual urbanization should have begun in the Iron Age.

From the beginning of the Iron Age, for the first time, it is possible to come across a word similar to "fins" in writing. It is the Roman Tacitus who, as the first, mentions the word "Fenni" in his famous book "Germania". However, it is unclear whether this word is related to the Finnish people. The first Scandinavian documents that mention a "country of the Finns" are two rune stones: one in Söderby in Estonia, where the inscription "finlont", and one in Gotland with the inscription "finlandi" - both stones from the 11th century.

However Tacitus might have been referring -when writing about the "Fenni"- to the Sámi or their forebears, whose nomadic existence fits the description of Tacitus better than the agricultural peoples of the south. Nomadic cultures leave little archaeological evidence, but proto-Sámi sites do occur from roughly this period on, and it seems the Sámi migrated gradually northwards, probably displaced by the southerners. Verses of the Kalevala, derived from ancient oral tradition, seem to refer to this conflictual relationship.

In the south, the two main Finnish tribes, Hämenites (Swedish: Tavastians) and Karelians, lived separately, in the west and the east respectively, but were constantly at war with each other. Roman merchants probably contacted those tribes.

Older Roman Iron Age in Finland

The older Roman Iron Age, also referred to in the research literature as the B-period of the Iron Age, is a period related to the prehistory of Central Europe and the Nordic countries, which lasted from about 50 BC to 150/200 AD. The Roman Empire then pushed its borders all the way to the Rhine and the Danube. Strong Roman influences extended all the way to the Nordic countries.The Roman artifacts discovered are concentrated in Uusimaa, Southwest Finland, the Kokemäenjoki estuary and Southern Ostrobothnia. In these areas, metal objects were placed in the graves. Some partially developed population -with commerce merchant links- was also found elsewhere in coastal areas and inland (like in the area of Lake Finland, i.e. the so-called Luukonsaari pottery-producing population). There were also fishing industries in the coastal areas, but additionally there are also clear indications of agriculture and animal husbandry

In Uusimaa and at the mouth of the Kokemäenjoki River, there are so-called orchard cemeteries, which refer to connections with the regions of present-day Estonia and northern Latvia (thanks to the Roman amber trade: read for further information https://researchomnia.blogspot.com/2018/09/romans-in-lithuania-amber-trade.html). In southwestern Finland, in the area from Piikkiö to Laitila, there are many types of grave forms, the equivalents of which can be found in eastern Sweden (that are culturally related to the Roman civilization). According to an interpretation given by Professor Unto Salo in 1968, Germanic men had arrived in the area to procure furs for the Veikseljoki trade route (the northermost section of the famous "Roman amber road"). There are a lot of weapons in the graves, which, according to Salo’s interpretation, refers to the warlike ideals of the newcomers and the acquisition of furs through taxation. Additionally, a Roman "wine bucket" and a nice ring made of gold and silver are known from Laitila's Sonkkila cemetery, probably linked to the amber trade.

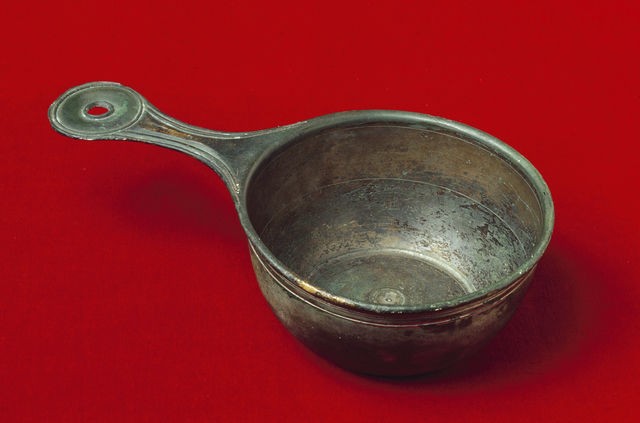

A bucket of wine from Vähästäkyrö. The object was originally made near Capua -60 km from Napoli (southern Italy)- in the 100s, but probably arrived in Finland from the northern parts of the Roman empire a couple of hundred years later (around 300 AD).

A bucket of wine from Vähästäkyrö. The object was originally made near Capua -60 km from Napoli (southern Italy)- in the 100s, but probably arrived in Finland from the northern parts of the Roman empire a couple of hundred years later (around 300 AD).

Southern Ostrobothnia has mound graves from this period. Younger Roman Age in Finland

Archaeological finds are known mainly from the coastal areas of Uusimaa, Southwest Finland and Southern Ostrobothnia, where metal objects (weapons and jewelery) were buried. Tomb finds are also known from Pirkanmaa, Kanta- and Päijät-Häme, Central Ostrobothnia and even Central Finland (Viitasaari).

Since the 1980s, Oulu archaeologists have also found cemeteries (burial sites) on the shores of the Gulf of Bothnia (Kaakkuri in Oulu, Tervakangas in Raahe (Saloisten), Rakanmäki in Tornio). In other parts of the country, residence finds also indicate civilized -meaning: partially Romanized- settlement (eg.: Luukonsaari pottery in Lake Finland, similar to Roman pottery).

The population of Finland's coasts maintained connections to both Scandinavia and the Baltics, in addition to which some objects also arrived from the residential areas of the Finnish-speaking population in Central Russia.

Rich grave finds at Laitila's Soukais and Salo's (formerly Uskela) Ketohaaa tell about the formation of some kind of social "upper class", mainly after the third century. Two parallel stone chests were found in the mound tomb of Soukainen, one of which contained a pair of Roman-style spearheads. The richer stone coffin had a pair of spearheads, a shield, a sword in a silver sheath, and a glass Drinking Horn & a bronze bucket made in the territory of the Roman Empire. Professors Ella Kivikoski and Unto Salo have interpreted the graves as belonging to a great man from Gotland, even a "prince", and his weapon bearer. Archaeologist Christian Carpelan, for his part, has also seen local features in the tomb and regarded it as evidence of connections in many different directions. Pieces of a golden neck ring are known from the mound of the keto, which refer to high-level connections to Scandinavia. A famous golden necklace has been found in the area as early as the 18th century, and it is preserved in Stockholm.

The population of Finland's coasts maintained connections to both Scandinavia and the Baltics, in addition to which some objects also arrived from the residential areas of the Finnish-speaking population in Central Russia.

Rich grave finds at Laitila's Soukais and Salo's (formerly Uskela) Ketohaaa tell about the formation of some kind of social "upper class", mainly after the third century. Two parallel stone chests were found in the mound tomb of Soukainen, one of which contained a pair of Roman-style spearheads. The richer stone coffin had a pair of spearheads, a shield, a sword in a silver sheath, and a glass Drinking Horn & a bronze bucket made in the territory of the Roman Empire. Professors Ella Kivikoski and Unto Salo have interpreted the graves as belonging to a great man from Gotland, even a "prince", and his weapon bearer. Archaeologist Christian Carpelan, for his part, has also seen local features in the tomb and regarded it as evidence of connections in many different directions. Pieces of a golden neck ring are known from the mound of the keto, which refer to high-level connections to Scandinavia. A famous golden necklace has been found in the area as early as the 18th century, and it is preserved in Stockholm.

Significant cemetery sites include Kärsämäki and Saramäki in Turku (formerly Maaria), Sonkkila and Untamala in Laitila, Kroggårsmalmi in Karjaan, Koskenhaka in Piikkiö and Vanutehtaanmäki in Salo. Very rich burials, rich in burials (and nice luxuries), are exceptions, with most burials scarce or completely undiscovered. It is possible that the occasional generalized undiscoveredness reflects social conditions, variations in burial practices, and/or connections to neighboring areas. The majority of objects imported to Finland during the Roman Iron Age come from the Baltic Sea region. The number of “Roman objects” found in Finland is very small compared to, for example, southern Scandinavia. Certainly there are a dozen items and money from the provinces of Rome or (in a couple of cases) from Italy. Several other objects show the Roman influence, even though they were made elsewhere (usually in Germany).

A re-assembled Drinking Horn (found in 47 parts) from the younger Roman period found in the Soukais of Laitila. In the same burial, Hemmoor-pail, pieces of two green drinking horns have been found in Salute Vanutehtaanmäki. Glass drinking horns were typically provincial Roman objects.

Only a few weapons referring to the Roman Empire have been found: a pugio-type dagger from Maaria's Kärsämäki (the dagger is shaped from a sword by forging it again) and three gladiators, or double-edged, Roman swords from Kaarina, Maaria's Saramäe and Kärsämäki. Pugio is possibly an original Roman object, but the gladiator swords are imitations of the ones of the Elbe and Veiksel. Pugies have been found in few areas north of the Roman provinces, which has been considered evidence of their Romanity (i.e., this type of pugio was not widely copied, like some other Roman artifacts).

To sum up, only a few objects are known in Finland that certainly originate in the Roman Empire. Although the territory of Finland cannot be considered to be under the influence of Rome, the artefacts of Finland from the Roman Iron Age definitely show connections to at least the northern provinces of the empire (like Germania I & II, Noricum and Pannonia). The Roman objects and money that ended up here were probably related to trade and other regular contacts from Finland to southern Scandinavia, the Baltics, and the settlements of the Germanic tribes.

|

| Turku Castle on its early stages during the 1200s |

The Romans who travelled north for ‘the gold of the Baltic’ would take with them various items to be traded, including fabrics, ceramics, metal objects, trinkets, wool, as well as bronze and brass artefacts. They brought back sacks of amber, animal skins, wax, feathers and beaver coats. Due to increasing intense economic contacts, Roman coins also were started to be used (nearly one thousand "solidii" -from the fourth and fifth centuries AD- have been found in the southern Scandinavia region and a few also in Finland, please read numismatics.org/digitallibrary/ark:/53695/nnan59692).

But actually there it is not a huge research by academics on this matter. However new studies are being done and soon we'll be published.