This area was one of the most romanized of the Roman empire in the fourth century, when started the barbarian invasions in western Europe: it was similar in everything to "Roman Hispania", according to the famous historian Theodor Mommsen.

Roman emperor Macrinus, a romanized berber born in Caesarea (now Cherchell in Algeria)

Roman Africa was populated by the autochtonous "Berbers" who were fully "latin speaking" in an area that coincides with actual central-northern Tunisia and who were fully christians on the coastal regions (from Gibraltar to modern Tripolitania).

There were also some descendants of the Phoenician settlers that founded Carthago, but they were assimilated by the autochtonous Berbers by the fourth century (indeed the same happened with some italian colonists that settled in coastal Numidia, mainly around Cirta).

But after the arrival of the Arabs in the late seventh century it "disappeared" in a terrible bloodbath. While Hispania remained forever linked to Rome, this African region lost nearly all the Romanization & the links with western Europe -from the local neolatin language to the early christianity (https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Extinction_of_the_Christian_Churches/r1RbAAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=christians+of+tunis&pg=PA241&printsec=frontcover).

However something of Roman Africa has survived, like the few Christian Berbers of our times and the small Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla

Indeed estimates show that actually there are nearly half a million Christian Berbers, many living in a situation of diaspora in Western Europe and the Americas and nearly 300,000 living in the Maghreb region of North Africa (from Morocco to Libya).

Notable Romanized Berbers

Accomplished Berbers of Roman Africa include famous writers such as Martianus Capella. There were also Christian saints such as Augustine, Roman popes such as Pope Victor I and even the pagan Roman emperors Macrinus & the famous Septimius Severus.

Most of them appeared in a socio-cultural period of development in Roman Africa following the introduction of Christianity. Most of these figures are historical, and we have to remember that now the Christians in North Africa do not have as much of a dominant community as they used to have in Roman times.

Roman writers such as Terentius, Lactantius, Martianus Capella (previously mentioned), Marcus Cornelius Fronto, Apuleius and Tertullianus were Berbers. Christian Berber saints include the Scillitan Martyrs, Cyprian, Victor Maurus and Saint Monica (mother of Saint Augustine). Roman popes like Pope Miltiades and Pope Gelasius I and Roman emperors such as Macrinus, Emilianus and Caracalla (son of the famous Septimius Severus) were also romanized Berbers.

Berber kings of exclusive Christian Berber realms known as the 'Romano-Berber states' include Masuna, Mastigas and Garmul of the "Kingdom of Altava", called initially "Mauro-Roman Kingdom" or "Kingdom of the Moors and Romans" (477-578 AD). They are known for making Christian Jedars and Mausoleums such as the "Tomb of the Christians" near Caesarea (also known as the 'Royal Mausoleum of Mauretania'). Also Caecilius (often called Koceila in berber language) of the Kingdom of Altava was an important Christian Berber.

History

The massacre of Christian Berbers by the Arab conquerors is one of the biggest exterminations in History. Nearly 90% of the Berbers living in actual Tunisia and Algeria "disappeared" in a few decades, with their own romano-berber civilization. Most of them died, but more than 350,000 were enslaved and sold in the slavery markets of the Arabs. A shameful genocide/ethnocide that only now is being studied and analyzed in all its enormous dimensions.

We know that the Kingdom of Altava (578-708 AD) fought harshly the Arabs. The last recorded ruler of the Kingdom of Altava was Caecilius, called Koceila or Kusaila ("leopard" in 'Tamazight' berber language). He died in the year 690 AD fighting against the Muslim conquest of the Maghreb. He was also leader of the Awraba tribe of the Imazighen and possibly Christian head of the Sanhadja confederation. Caecilius as a berber prince was probably educated in a roman christian way and consequently fought the moslem invasion with religious passion. He is known for having led an effective Berber martial resistance against the Umayyad Caliphate's conquest of the Maghreb in the 680s.

Indeed, in 683 AD the arab leader Uqba ibn Nafi was ambushed and killed in the Battle of Vescera near Biskra by Kusaila, who forced all Arabs to evacuate their just founded Kairouan and withdraw to Cyrenaica. But in 688 AD Arab reinforcements from Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan arrived under Zuhair ibn Kays. Caecilius met them in 690 AD -with the support of Byzantine troops- at the Battle of Mamma. Vastly outnumbered, the Awraba and Byzantines were defeated and Caecilius was killed. With the death of Caecilius, the torch of resistance passed to a tribe known as the Jerawa tribe, who had their home in the Aurès Mountains: his Christian berber troops after his death fought later under Kahina, the last Queen of the romanized Berbers.

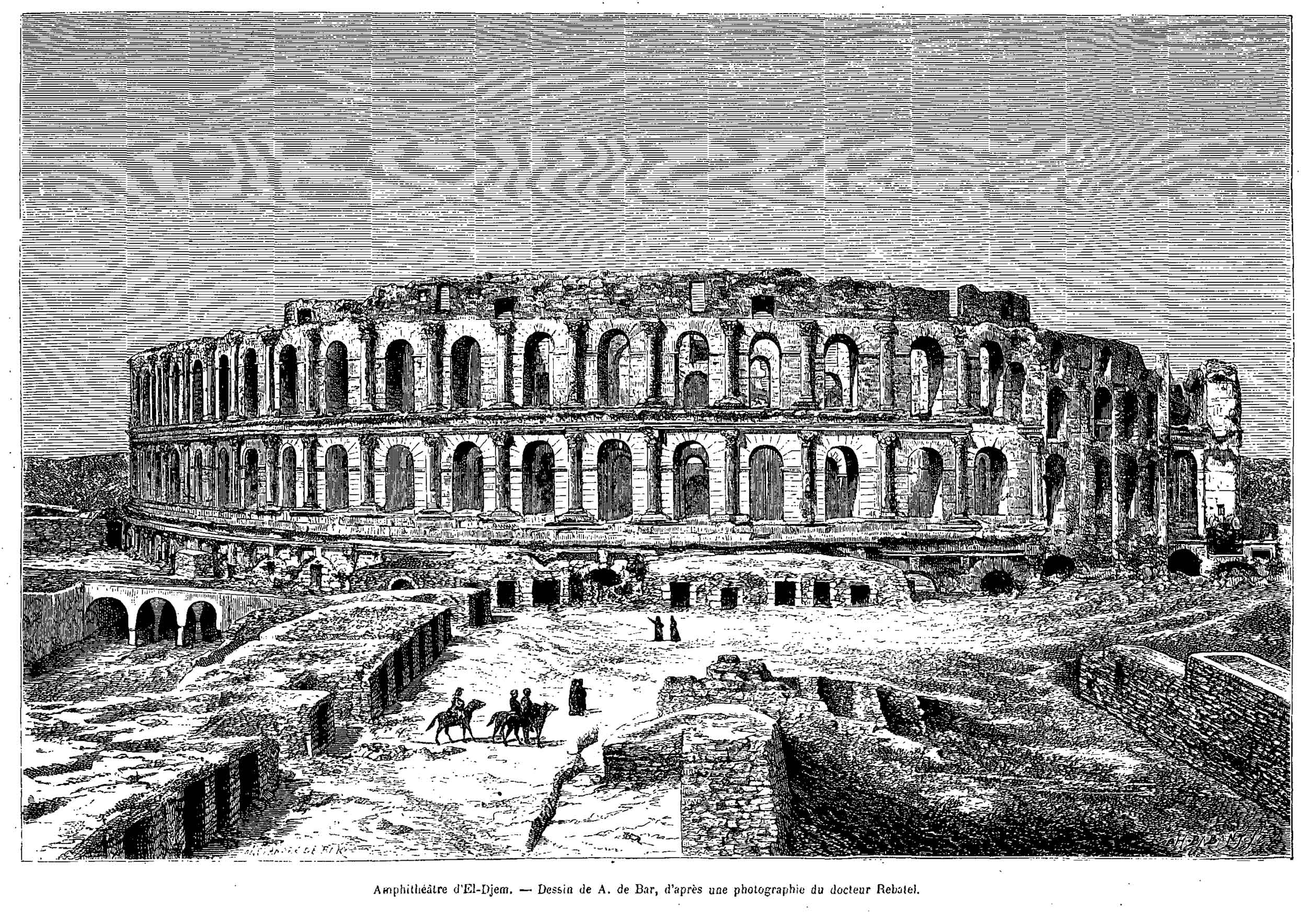

Kahina (called also Dihya) was born in the early 7th century and may well have been of mixed descent: Berber and Byzantine Christian, since one of her sons is described as a 'yunani' or Greek. Kahina ruled as a Christian queen (but some arab historians wrote that she was a Jewish "sorcerer") and was able to defeat the Arab invaders who retreated to Tripolitania: for more than five years ruled a free berber state from the Aures mountains to the oasis of Gadames (695-702 AD). But the Arabs, commanded by Musa bin Nusayr, returned with a strong army and defeated her. She fought at the El Djem Roman amphitheater of Thysdrus, but finally died around the beginning of the eight century (most probably in 703 AD) in modern-day Algeria in a battle near Tabarka. Her defeat and death was followed by the "disappearance" of Roman Africa in what the Arab conquerors later called 'Maghreb' (the word 'maghrib' means "western territories" in arab language).

Musa bin Nusair, a Yemeni general, was made governor of "Ifriqiya" (as Arabs called Roman Africa) and given the harsh responsibility of putting down this renewed romanized Berber rebellion and converting the population to Islam. Musa and his two sons prevailed over Queen Kahina and the rebels and enslaved 300,000 Berber captives. The caliph's portion was 60,000 of the captives. These the caliph sold into slavery (mainly in Damascus), the proceeds from their sale going into the public treasury. Another 30,000 captives (who rejected their Christian faith in order to survive) were pressed into military service and forced to convert to Islam.

We know that all Roman Africa had only one million inhabitants when Musa enslaved those 300,000 Berber captives....and this means that one third of the Romanized Berber population was reduced to slavery in those years! Furthermore 60,000 were sent mostly to Damascus. We know that in those years the Arabs did not have a huge navy, so most of those captives had to reach Damascus (in Syria) walking by foot thousands of kms! Imagine the massacre along the way through the desert of Libya and western Egypt! As an example, we know that in the XX century the moslem Turks forced many christian Armenians to walk a few hundred kms in captivity and there was the death of nearly one quarter of them: consequently imagine how huge was the massacre suffered by those Berbers enslaved, forced to walk in captivity the big distance between their homeland until Damascus....It was one of the most terrible exterminations of an entire population in ancient History!!!!

The El Djem Roman amphiteater was a stronghold of Queen Kahina: it was destroyed by the Arabs around 701 AD after a fierce defense by the romanized Berbers.

Historian Daniel Pipes also wrote in his famous book 'Slave Soldiers and Islam: The Genesis of a Military System' (https://books.google.com/books?id=ByLG-2hZX-MC&q=musa+300,000&pg=PA124#v=snippet&q=musa%20300%2C000&f=false), that Musa Nusayr enslaved nearly 300,000 berbers in those years when defeated Kahina and reduced nearly to ashes for two centuries the city of Carthago! Indeed in 705 AD Roman Carthago was reduced from 500,000 inhabitants during Trajan/Hadrian years to a village full of ruins with just 3,000 survivors (all Muslims, of course).

Additionally we must remember that when lived the most famous Christian Berber in Antiquity, Saint Augustine, there were five million inhabitants in the provinces of the Roman empire that now are called the "Maghreb", but -after the 50 years of Muslim Arab conquests- in 705 AD there were only one million Berbers (while nearly all the Roman colonists' descendants were murdered or flew back to Italy) and one third of them was enslaved: this was one of the biggest massacres registered in History, with the bloody end of nearly all Christianity in the region.

Capsa & the last Romanized Christians

Only a few areas of Roman Africa maintained (in the moslem Maghreb) until the early XVI century the so called "African Romance" language and practised christianity: one of them was Capsa.

The Roman town of Capsa, now modern day Gafsa in Tunisia, was conquered by Rome in 106 BC and made a colonia and municipium by emperor Trajan. It grew in importance as can be seen in the Roman baths that were 4 meters deep and the recently discovered mosiacs. During the decades of Septimius Severus the town had more than 300,000 inhabitants and was a key important commercial center of the Roman limes in Africa. Capsa was a fully romanized city by the third century.

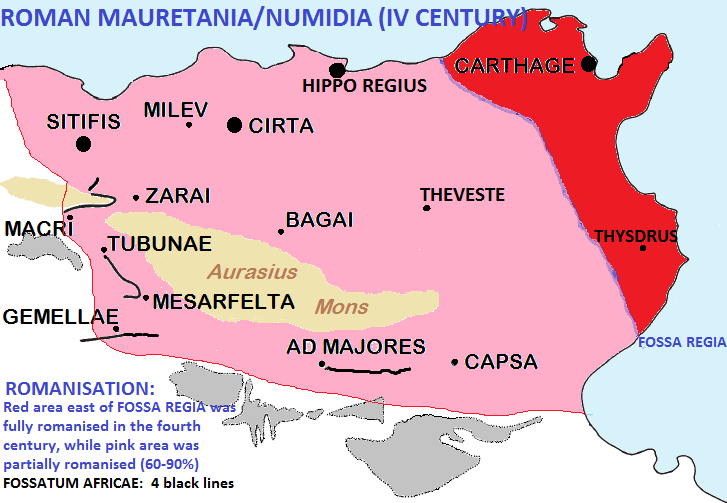

Map I created for wikipedia, showing Capsa location in the Romanized areas of Roman Africa

Although Capsa was conquered by the Vandals, it soon became independent and the capital of a newly founded Romano-Berber kingdom in the 6th century (until happened a Byzantine invasion).

Under the Byzantines the city was the capital of the Bizantine province "Byzacena" and enjoyed a period of economic revival. General Solomon build in 540 a new city wall and named the city "Capsa-Justiniana".

When the Arab Oqba Ibn Nafi conquered Capsa in 688 AD he faced fierce resistance from the Berbers, during & after the Arab conquest. It however subsequently lost importance to the Muslim founded Kairouan. Christians living there still were considered Romanized Berbers and continued to speak an "African Latin" as part of their language and remained loyal to the Christian religion.

Capsa is the last place in North Africa where speakers of African Romance could be found "officially" in the thirteenth century, and Christianity was found there for another century, worshiped also in the Roman pools of the old ruins. Christians moved towards Capsa and its surroundings around the 10th century, strengthening its position.

In 1135 to 1155 the Normans conquered Capsa and protected the Christians there for a few years until the Muslim Almohads reconquered the city. Ibn Khaldun hinted at a native Christian community in 14th century in the villages of Nefzaoua, south-west of Tozeur and not far from Capsa. These paid the "Jizuah" and had some people of Sardinian descent among them.

After 1170 the remaining North African churches began to decline and disappear. This was a slow process, and popes continued to appoint bishops to sees like Carthage and Tripoli until the middle of the thirteenth century, but traces of organised, indigenous Christian communities become rare after that time.

Additionally we must pinpoint that the presence of Berber Christians in Libia's Tripolitania is attested at least until the late eleventh century and in the Jebel mountains for another century(https://books.google.com/books?id=pIkmvKB8OlsC&pg=PA121&lpg=PA121&dq=christians+of+Gef%C3%A0ra&source=bl&ots=wq6i_ZLi8O&sig=hdNYBH-szy0dBcioINSxoJwYl_k&hl=en&sa=X&ei=EwyFU4bLO9GEqga474LYAw&ved=0CCkQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=christians%20of%20Gef%C3%A0ra&f=false): in the necropolis of En-Gila to the south of Tripoli, a dozen Latin texts dating between 945 and 1003 were discovered (https://www.cairn-int.info/article-E_RHR_2293_0325--byzantine-churches-converted-to-islam.htm#re66no66).

In the second half of the fifteenth century, the Roman humanist Paolo Pompilio noted that the territory of Gafsa was populated by a land of small villages in which the inhabitants spoke a "Latinity" language. Berber Christians continued to live there until the 15th century, while they didn't recognize the new Catholicism of the Renaissance Roman Papacy. This would perhaps deny them support from other Christian powers. A letter in Catholic Church archives from the 14th century shows that there were still four bishoprics left in North Africa (http://www.orthodoxengland.org.uk/maghreb.htm): it was a sharp decline from the over four hundred bishoprics in existence at the time of the Arab conquest!

French photo of two young Christian Berbers of the Algeria's Kabylia in the XIX century

The Berber Christians of Roman Mauretania's Septem (actual spanish Ceuta) seem to have been assimilated into the Christianity of nearby Spain. Septem was another pocket of Christianity left over from the Roman period, at least until the X century. Then, in the 1400s Spain conquered the city and Christianity returned to be worshipped in Ceuta, but it was Catholicism linked to Madrid.

In the first quarter of the fifteenth century, the native Christians of Tunis, even though they were heavily assimilated into Islam in various aspects, extended their church, as the last Christians from all over the Maghreb were gathered there. This is the last reference to native Christianity in North-West Africa; Tunis and Capsa seemed to be the last Christian citadels for over fourteen hundred years of continuous Christianity.

Several families of the old African Christian Church were found in Tunis when the spanish emperor Charles V landed there in 1535. Leo the African described the remaining autochtonous Christians in Tunis with these words:

"In the suburb near the gate of El-Manera is a particular street, which is like another little suburb, in which dwell the 'Christians of Tunis'. They are employed as the guard of the Sultan and on some other special duties".

The "Christians of Tunis" survived until 1583, when the Turks conquered the city and ordered the extintion of the local christianity. Native romanized Christianity was assimilated into Islam, and it died out forever all over the Maghreb.

For the following centuries, until the XIX century and the arrival of the French in the arabised Maghreb, practically no Christianity was worshipped in this northwestern-african region. But -of course- the spanish Ceuta and Melilla were the exception (as happened even with Algeria's Oran until 1792, when the city was given by Spain to the Algerian Turks/Arabs).

.png/1024px-Bulgarian_national_revolutionary_movement_in_Macedonia_and_East_Thrace_(1893-1912).png)

_(14578445319).jpg)

.jpg)

%2C_Deva_Victrix_(Chester%2C_UK)_(8392251460).jpg/407px-The_angle_tower_how_it_would_have_appeared_with_legionaries_and_their_lethal_stone-throwing_catapult_(ballista)%2C_Deva_Victrix_(Chester%2C_UK)_(8392251460).jpg)