Romans created colonies for their veterans in the territories they conquered. Four were created in the British isles. The following essay is a brief research on one of these colonies in Roman Britannia: Camulodunum (actual Colchester).

The 1st century colonies at Camulodunum/Colchester (Colonia Claudia Victricensis), Lindum/Lincoln (Colonia Domitiana Lindensium), and Glevum/Gloucester (Colonia Nervia Glevensium) were founded as settlements for legionary veterans. The creation of three coloniae on the sites of earlier fortresses was a useful expedient whereby time-served legionaries could be discharged, form a military reserve, and receive their due grant of land with minimal disturbance of the native population.

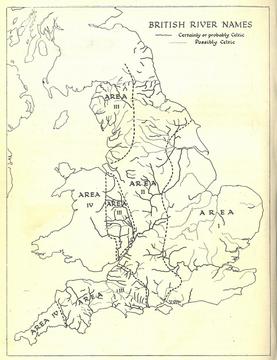

Map showing the four colonies of veterans in Roman Britannia and the area Romanized & populated by the Romano-Britons around these colonies in 410 AD. Note that the 3 original colonies enclosed a perfect equilateral triangle, later expanded to the north with the creation of the veterans' colony of Eburacum by emperor Septimius Severus (when he tried the full conquest of Caledonia/Scotland in the third century)

In contrast, the sites of the fortresses at Exeter (Isca Dumnoniorum) and Wroxeter (Viroconium Cornoviorum) became tribal centers of the local Britons.

The only other known Roman colonia in Britain, at Eboracum (York), is generally believed to have been promoted to this status in the early 3rd century.

It is noteworthy to remember that Tacitus wrote that in winter 84 AD all Britannia was fully conquered by the Romans: even all Caledonia/Scotland.

He wrote that under Agricola "Britannia perdomita est" (Britain is fully dominated), where the word 'perdomita' in latin is a reduction of the words "PERfecta DOMInaTA" (in English: totally conquered/dominated). Of course Agricola -after his victory against the Picts (called "Caledonians" by the Romans) at the battle of Mons Graupius in the fall of 84 AD- in spring 85 AD was ordered to leave Britannia and went back to Rome, so he could not consolidate his full control of all the huge island of Britain. Romans soon dismantled also the huge Inchtuthil fort in the 'Gask Ridge' and went south of what is now the 'Antonine Wall', losing control of Caledonia after only a few winter months of full rule.

But in the southern half of Britannia they ruled the country for many centuries and settled there many thousands of their veterans. Furthermore, the genetic signature of the haplogroup "R1b-U152" (ancient Romans, from the original founders of Rome to the patricians of the Roman Republic, were essentially R1b-U152 people) is found at low frequency almost everywhere in the British Isles, but it is considerably more common in eastern and southern England (5-10%), reaching a peak of more than 15% in East Anglia and Essex (around Camulodunum and St. Alban) and in Kent.

In Roman Britannia the majority of administrators, land owners and legionaries (at least in the first century of Romanization) would have hailed from Italy: it is possible that approximately one third of the autosomal genes in the actual British population comes from Mediterranean people (mostly Italians, but also Iberians, Greeks, Anatolians and a few Egyptians, Berbers, Phoenicians, etc...), who settled in Britain during the Roman period (read for further information:https://www.eupedia.com/genetics/britain_ireland_dna.shtml#romans).

Indeed the area of the British isles within (and "protected" by) these four colonies was the most Romanized of ancient Britannia (read for additional information: https://suscholar.southwestern.edu/bitstream/handle/11214/227/Broyles.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y).

It is noteworthy to pinpoint that these four cities were the few Roman settlements in Britain designated as a 'Colonia' rather than a 'Municipia', meaning that in legal terms it was an extension of the city of Rome, not a provincial town. Its inhabitants therefore had full "Roman citizenship" with all the related rights.

In the third century in Roman Britannia there were nearly 4 million inhabitants, enjoying an era of prosperity that the same Winston Churchill admired (in his famous "A History of the English-Speaking Peoples"). But after the plague of the Antonine period, plus other negative circumstances (like the withdrawal of all the Roman military) in the mid fifth century there were only half of them: less than 2 millions. Even if it looks very strange, they were dominated by 200,000 Anglo-Saxons in a few decades after the Romans left the British isles. Some scholars think that the reason (probably together with the plague of 450 AD) was that only the cities were fully Romanized, but less than 20 percent of the Britannia population lived there, while the peasant/farm areas (where most people lived) were only minimally Romanized and did not know how to defend themselves from the strong & well organized German invaders in the fifth century.

However the Romano Britons were able to stop for some decades the Anglosaxon conquests, with their legendary Badon hill victory around 500 AD (under the leadership of the Romano-Briton Ambrosius Aurelianus, who was identified by the scholar J. Morris as -perhaps- the legendary King Arthur). This happened in the same years when the last fully Roman emperor -Justinianus- did the tentative to reconquer all the western roman empire, that has previously fallen in the barbarian control (and the Romano Britons probably received some help & military advice from him).

Additionally we must remember that the Plague of Justinian (that killed as many as 100 million people across the world: as a result, Europe's population fell by around 50% between 540 and 600 AD !) entered the Mediterranean world in the 6th century and first arrived in the British Isles in 544 or 545 AD. Just before the battle of Dyrham in 577 AD, that was the beginning of the final conquest of Subroman Britannia by the Anglosaxons: the important Romano-britons city of Calleva was abandoned in those years, because hard hit by this terrible plague.

Richard Lehman wrote that "....in 550 AD, the island of Britain was predominantly Romano-British: they were unable to maintain a full urban civilisation after the departure of the Romans in 410 AD, but were successful at keeping the Angles and Saxons confined to Anglia and Kent (after the battle of Badon Hill). There was no trade or social exchange between the Christian British and the pagan Angles and Saxons, once they had had fought each other to a standstill under King Arthur. The British carried on some trade with the Mediterranean, whereas the English lived on what they could grow. So when the plague reached Britain in boats from mainland Europe, it killed up to half of the native Romano-British population but left the English colonists largely unscathed. Not long afterwards, the English began to mount probing raids into British territory and found that there was little opposition. They sent word back to their relatives in Schleswig-Holstein and the Danish peninsula that the whole island was up for grabs. The king of the Angles was so impressed that he put his entire population into boats and left the area west of Hamburg deserted for several centuries. And so, 150 years after Hengest and Horsa first brought in Saxon warriors to police the borders of crumbling Roman Britain, the English decisively colonised plague-ravaged Britain from the borders of Wales to the middle of Scotland...…"

Map of southern Sub Roman Britain in 575 AD, just before the "Battle of Dyrham", showing the areas of Romano-Britons, Saxon & Jute settlements according to the historical sources (Bede)

Furthermore, scholars such as Christopher Snyder (read http://www.the-orb.arlima.net/encyclop/early/origins/rom_celt/romessay.html) believe that during the 5th and 6th centuries – approximately from 410 AD when Roman legions withdrew, to 597 AD when St. Augustine of Canterbury arrived – southern Britain preserved a sub-Roman society that was able to survive -for a while- the attacks from the Anglo-Saxons and even use a vernacular Latin (called "British Latin") for an active culture. There is even the possibility that this vernacular Latin lasted to the late 7th century in the area of Chester and Gloucester, where amphorae and archaeological remnants of a local Romano-British culture (mainly in the locality called 'Deva Victrix') have been found.

Indeed -according to H. R. Loyn (in his "Anglo-Saxon England and the Norman Conquest". Harlow: Longman; p. iii; 1962)- as late as the eighth century the Saxon inhabitants of St. Albans (an important city nearly 70 km west of Camulodunum) were aware of their ancient neighbors of the Roman city called 'Verulamium', which they knew as "Verulamacæstir" (the fortress of "Verulama"), possibly a pocket of Romano-British speakers remaining separate in an increasingly Saxonised area.

Scholars have seen signs of continuity between many "late" Roman towns and their medieval successors. Urban continuity has been confirmed for Bath, Canterbury, Chester, Chichester, Cirencester, Exeter, Gloucester, Lincoln, London, Winchester, Worcester, and York. At Verulamium (St. Albans), where the medieval town grew up around the Saxon abbey outside of the Roman walls, archaeologists found several late fifth-century structures and a newly-laid waterpipe indicating that a nearby Roman aqueduct was still providing for the town's sub-Roman inhabitants in the sixth century. At Silchester, which did not become a medieval town, excavations revealed that economic activity at the forum continued into the fifth century (dated by coins and imported pottery and glass), while jewelry and an ogam inscribed stone hint to late sixth century contacts with Irish settlers (read for further information: http://www.vortigernstudies.org.uk/artgue/snyder.htm).

Indeed the British economy did not collapse during the early Sub Roman period. Although no new coinage was issued in Britain, coins stayed in circulation for at least a century (though they were ultimately debased); at the same time, barter became more common, and a mixture of the two characterized 5th (and early 6th) century trade. Tin mining appears to have continued through the post-Roman era, possibly with little or no interruption. Salt production also continued for some time, as did metal-working, leather-working, weaving, and the production of jewelry. Luxury goods were even imported from the continent -- an activity that actually increased in the late fifth century. Only after the mid sixth century started a deep crisis for the Roman Britons: this fact coincided with the decades of the terrible "Constantine plague" (that reached Britain around 545 AD).

CAMULODUNUM/COLCHESTER

Balkerne Gate, a 1st-century Roman gateway in Camulodunum, it is the largest surviving gateway of Roman Britain

The foundation of this Roman colony of veterans -at the English site named 'Colchester' today- took place in AD 49. The actual name is derived from the Latin words 'Colonia' and 'Castra' (chester in ancient Brythonic). The Roman town began life as a Roman Legionary base constructed in the AD 40s on the site of the Brythonic-Celtic fortress (called 'Camulodunum' by the Romans) following its conquest by the Emperor Claudius. After the early town was destroyed during the Iceni rebellion in 60/1 AD, it was rebuilt: it reached its zenith in the 2nd and 3rd centuries, when the city had a population of more than 30,000 inhabitants (some historians argue that could have had nearly 50,000 citizens, including the many "villas" in the surrounding areas). During this time it was known by its official name "Colonia Claudia Victricensis" (usually called "COLONIA VICTRICENSIS) and as 'Camulodunum', a Latinised version of its original Brythonic name.

Tacitus tells us that it had a dual purpose: as a military base in the hinterland of the frontier zone, and as a model of Roman urban life (Tacitus Ann., 12.32). This statement has some support from archaeological excavations: some military barracks were not demolished but continued to be used in modified form in the early colonia, while at the same time public buildings were being erected and a new street system laid out to the east of the fortress site.

On the other hand, the early colony had no defences: after the events of AD 61 (when the Britons revolted under queen Boudicca), this mistake was not repeated. Evidence has been found near the Balkerne Gate, the later west gate of the town, for a defensive system built soon after the Boudican revolt, consisting of a ditch and presumably also an earth bank. This line was abandoned around 75 AD when the defended area was apparently extended westwards, the former western boundary being marked by a monumental arch. This arch was incorporated into the new Balkerne Gate when the city wall was built along the line of the earliest western defences in the early 2nd century (if interested in some nice maps of Roman Britain showing also Camulodunum, please go to https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archives/view/romangl/map.html.

The main building of the city was the "Temple of Claudius", which dominated the landscape and was a lavish building decorated with marbles and porphyry imported from various parts of the Mediterranean world. Today the remains of the Temple forms the base of the 'Norman Colchester Castle': it was one of at least eight Roman-era pagan temples in Colchester (read https://web.archive.org/web/20140603222036/http://www.roman-britain.org/places/colchester_temples.htm) and was the largest temple of its kind in Roman Britain; its current remains potentially represent the earliest existing Roman stonework in Great Britain. On the west side of the colony a monumental gate of two arches, part of which survives as the actual 'Balkerne gate', was erected on the site of the Porta Decumanus. There is some uncertainty about the date of the arch, but it was probably erected c. 50 A.D. to commemorate the foundation of the colony.

Colchester also housed two of the five Roman theaters unearthed in Britain, one of which, located in Gosbecks (site of the home of a tribal chief of the Iron Age) was in the first century the largest in Roman Britannia, as capable of accommodating up to 5000 spectators. Furthermore it is noteworthy to pinpoint that in 2004, the 'Colchester Archaeological Trust' discovered the remains of a Roman Circus (chariot race track) underneath the Garrison area in Colchester, a unique find in Great Britain.

Some fine stretches of the Wall at Colchester survive, although in places the front was refaced in the medieval period. Built of alternate layers of "septaria" and mortar, with tile courses in both inner and outer faces, it was about 3 m wide at its base and slightly narrower above. Several interval towers have been found, all presumably contemporary with the wall.

Apart from the blocking and refacing of the 'Balkerne Gate' (sub roman/late Saxon-early Norman?), there are only slight traces of this rebuilding before the late medieval refacing. The dating evidence shows that the Wall was built between AD 100 and AD 150.

The 3 m wide wall of Colchester could easily have accommodated a wall-walk, although wide free-standing walls were most unusual in Britain before the late 3rd century. Their erection at Colchester at such an early date in comparison with other British towns must surely have been connected with the city’s colonial status.

The period between the mid 2nd and the early 3rd century saw in Roman Colchester, as in other towns of Roman Britannia, the appearance of substantial, well built town houses. Areas which had been used for cultivation were built over in response to the need for new building land within the walls. The houses themselves were often larger and of better quality than earlier ones, the courtyard house making its first appearance. Rubble foundations became the norm, especially for internal walls, and floors were frequently tessellated. Clearest testimony to the increase in affluence is the widespread introduction of mosaic pavements. Over 30 mosaics have been recorded in the town and, as far as can be judged, the overwhelming majority are of the period 150-250 AD.

Roman Walls of Camulodunum in modern Colchester

The pottery industry in particular was important to the local economy.

It was active from the Claudio-Neronian period to at least the late 3rd or early 4th century.

It was at its most successful from c. 140 to c. 230 AD, when large quantities of pottery were being exported to other parts of the country, especially to forts on the northern frontier.

For detailed information, please read data and see maps on the link: https://englaid.wordpress.com/2015/01/09/mapping-pottery/

Coins may have been struck in Colchester in the late 3rd century and the first half of the fourth century, when the city and the surrounding territory was fully Romanized (according to academics like John Morris). The 4th century did see an increase in the bone-working industry for making furniture and jewelry. And evidence of blown-glass making has also been found in Camulodunum.

Christianity was very important in the fourth century. During this period a late Roman church just outside the town Walls was built with its associated cemetery containing over 650 graves (some containing fragments of Chinese silk), and may be one of the earliest churches in Britain.

Additionally the huge Temple of Claudius, which underwent large-scale structural additions in the 4th century, may also have been repurposed as a Christian church, as a 'Chi Rho' symbol carved on a piece of Roman pottery was found in the vicinity.

With the withdrawal of the last Roman troops in 410 AD, the city -probably reduced to less than 5,000 inhabitants- started to suffer the attacks from the Saxons. A skeleton of a young woman found stretched out on a Roman mosaic floor at Beryfield, within the SE corner of the walled town, was interpreted as a victim of a Saxon attack on the Sub-Roman town in the first decades of the fifth century.

The fate of the Romano-British population of Colchester is unclear but life in the town was certainly radically different by the mid 5th century, the date of the earliest known Saxon presence in the city's area. It is uncertain whether elements of the Romano-British population survived the transition. Some houses were left standing and partially unoccupied, so that topsoil and broken roof accumulated on their floors. But some evidences suggest that some Romanized Britons (mixed with a majority of Saxon settlers) remained living inside the walls until the first decades of the sixth century.

Famous archaeologist Mortimer Wheeler pinpointed that the lack of Saxon archaeological remains in a triangle area between London, Colchester and St Albans could mean that there was a region "post-roman" were the Romanized Britons remained -for some decades- independent (surviving the Saxon invasions of southern Britain in the fifth century). One legend from the early 500s AD tells of a king by the name of Arthur, a Romanized Celt, who had a series of victories against the invading Anglo-Saxons. King Arthur's legend would grow during the Middle Ages, but his few victories were not enough to keep out the invaders.

Indeed historian John Morris in his masterpiece "The Age of Arthur" (1973) wrote that the Romanized Britons used to remember the prosperous centuries of Roman rule with nostalgia and so he suggested that the name "Camelot" of Arthurian legend may have referred to the first capital of Roman Britannia (Camulodunum) in Roman times.

Map showing Camulodunum in the King Arthur years.

Some historians (like John Morris) wrote that the 'Battle of Badon Hill', the famous victory of King Arthur and his Romano-Britons against the Anglo-Saxons (that blocked their advance & conquest of Britannia for nearly half a century), was probably fought in the proximity of Camulodunum around the year 500 AD

---------------------------------------------------------------------

I want to add to the above essay -written by B. D'Ambrosio of the University of Genova- the following excerpts of researches done by Peter Kessler and others, related to Camulodunum and other Roman cities during the sub-roman decades (from https://www.historyfiles.co.uk/FeaturesBritain/BritishSouthernBritain03.htm):

In most of the towns of Roman Britain, the usual civic life continued well into the fifth century after the legions' departure in 410 AD. Conscious attempts to live a form of Roman life persisted around early Christian churches such as those at St Albans, Lincoln, and Cornhill in London. Elsewhere, the populations of some Roman towns, such as Wroxeter and York, re-used old civic buildings for a more domestic purpose. The old bathing complex at Wroxeter was now the site of a large, timber town house surrounded by shops in a late Roman style. However there it is no doubt that the sub-Roman period was one of violent unrest. Hill-forts such as South Cadbury were re-occupied by Romano-British inhabitants, who strengthened their walls, presumably against some threat from invaders.

Indeed there are a series of regions, or territories, in the British south-east that get the most fleeting of mentions in various sources, with tantalising glimpses given of some of the possible Romano-Britons kingdoms that existed there in the short gap between post-Roman administration and Anglo-Saxon domination.

Brief mentions in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles give a vague picture of how the war was going, and centres of British resistance can often be deduced from the location of these battles, and from archaeological evidence.

Caer Celemion (Calleva)

Roman Calleva Atrebatum, the walled capital of one of the major southern Romano-British tribal cantons, could have survived as a possible Caer Celemion (modern Silchester) along with its southern neighbour, Caer Gwinntguic (Winchester). Evidence shows that Britons continued to command the territorium (formed roughly of Berkshire, and northern Hampshire and Wiltshire) into the seventh century, probably as a post-Roman continuation of the Celtic Atrebates. Local place names such as Andover, Micheldover and Candover are British-origin names.

This, together with an absence of early Saxon relics near Caer Celemion and a considerable number of male burials intrusive in prehistoric round barrows all along the nearby chalk country suggest casualties incurred in military operations and an unexpectedly vigorous persistence of sub-Roman authority in the region. There are also legends of a King Einion based around here.

Findings along the south of the Thames Valley (Caer Celemion's northern border) show that there were Saxons there from the early fifth century, in settlements at Reading, and further upriver at Abingdon, Dorchester and Long Wittenham. Saxon cemeteries and artefacts mix in with Roman material, suggesting these areas may initially have been settled by laeti to defend Caer Celemion's borders.

The Saxon settlements at Cassington and Brighthampton on the north side of the Thames above Oxford could well have started in a similar fashion (perhaps by neighbouring Cynwidion). However, when the encroaching Thames Valley Saxons reached them by around the 470s, the settlements became hostile territory for the British.

These laeti could have been supplied with sub-Roman metalwork from Calleva itself. It appears that in its final phase the basilica in the town centre was turned into a substantial metal-working area (Guide to the Silchester Excavations, M Fulford, 1982).

Another site which has produced very late Roman material is Lowbury Hill on the Berkshire Ridgeway overlooking the upper Thames basin (Caer Celemion's northeastern border). This apparently started as a pagan temple in late Roman times, but its final purpose was probably to serve as a look-out point related to the territory's outer boundary defences.

Further west, the fifth or perhaps sixth century construction of the Wansdyke was a massive undertaking which reached from west of Caer Baddan's capital (Roman Aquae Sulis, modern Bath) to the proposed northwestern corner of Caer Celemion's border.

The continuing vitality of sub-Roman Calleva during the fifth, and perhaps far into the sixth, century can be illustrated, not only by its substantial output of paramilitary metalwork and its probable maintenance of a defensible river frontier in the Thames Valley, where in the fifth century the main threat was from the Thames Valley Saxons.

It was also apparently protected by stretches of earthworks related to the Roman roads that led to it from the north and west. The existence of those in the north is unsurprising due to the obviously hostile relations between the sub-Roman Atrebates and the Thames Valley Saxons. Those to the west of Silchester may have been built in conjunction with the main section of the Wansdyke itself, leading west from Calleva along the Roman road which intersects, and was destroyed by, the Wansdyke.

Although Calleva's defences would have remained relevant throughout its survival, after the victory of Mons Badonicus and the peace which followed it, a new threat emerged from the south in the form of the West Seaxe, and the north-facing Wansdyke was no defence against it.

By 577, with the fall of three British kingdoms based around Gloucester (led by Caer Gloui), and the fall of Caer Gwinntguic to the south and southwest (probably in 552), Caer Celemion was totally isolated. It had the Thames Valley Saxons pressing it from the north and the much more powerful West Seaxe attacking from the south, and between about 600-610 it was destroyed, probably by Ceawlin of Wessex.

Unfortunately, there is no written record of the event. Despite almost certainly being the seat of a bishop in the fourth century in a conspicuously placed Christian church, by 634 Calleva's historic past had clearly been forgotten when Birinus chose the much smaller, and less significant, walled town of Dorchester-on-Thames as the centre of his mission to the West Saxons. Indeed Caer Celemion (Roman Calleva, modern Silchester in Hampshire) was certainly a centre of resistance by the British, as indicated by protective dykes that surround its northern borders. Legends exist of a giant named Onion living there. This indicates a potential leader, or king, called Einion. The appellation of "giant" could equate a strong or particularly tough warrior, appropriate for a British enclave that held out, almost entirely isolated, until the seventh century.

Map of mid 6th century when happened the "Battle of Dyrham", showing the area I borders occupied by the AngloSaxons conquerors (and defined by only a few not English names for the rivers).The battle was a major military, cultural and economic blow to the Romano-British because they lost the three cities of Corinium, a provincial capital in the Roman period (Cirencester); Glevum, a former legionary fortress (Gloucester); and Aquae Sulis, a renowned spa (Bath). Archaeological research has found that many of the villas in the post-Roman era were still occupied around these cities: this suggests the area was controlled by relatively sophisticated Romano-Britons. However they were eventually abandoned/destroyed as the territory came under the control of the Saxons. This quickly happened after the battle around the Cirencester region but the Saxons took many years to colonise Gloucester and Bath.

Caer Colun (Camulodunum)

A probable post-Roman British name for the important Roman town of Camulodunum (Colchester in Essex) and a potential kingdom or territorium based around it. There is no established British history for this region after internal British rule began, but although the Kingdom of the East Saxons (Essex) was founded circa 540, mercenaries are likely to have been settled along the coast for at least a century and a half before that date.

As with Caer Lundein, there is a marked lack of Anglo-Saxon relics in the area before the sixth century, which strongly suggests that Caer Colun could have held a surviving pocket of British power well into the mid-500s. That would also explain the comparatively late date for the founding of an East Coast Saxon kingdom.

Evidence from two Roman villa sites, at Little Oakley and Rivenhall, does demonstrate some early Saxon settlement in the territory. Distinctive early pottery from the filling of pits at Little Oakley provides evidence of occupation on the site of the villa, although it can tell us little about the nature of the settlement. Evidence from Rivenhall is more extensive and includes a post-built hall and a well, plus pottery and a glass vessel dating from the fifth century (AD 400-500).

This evidence of early Saxon settlers reusing Roman sites, and possibly even existing buildings and structures, is not unique to Essex, and parallels have been found, for example, at Darenth Roman villa site in Kent. What is unsure, however, is whether the evidence represents settlers using sites which were vacant, available, and easily converted for their use, or whether they were actually involved in the maintenance of the Roman estates, with the express permission of the existing landowner.

The mechanism and nature of the Saxon settlement of England, even on the level of how many foreign settlers arrived on these shores, remains unclear. What does seem certain, however, is that in Essex they did not encounter large-scale resistance from the natives. Also, the period from which these findings originate strongly suggests that they were from the settled Saxon laeti, and not the new wave of Saxons who began to infiltrate the region from the start of the sixth century.

After whatever Sub-Roman authority still existed in the region in the mid-500s presumably capitulated, Colchester seems to have become abandoned (which it certainly was by the seventh century)

Some sub-Roman territories or kingdoms are better attested than others. Those in the south-west may not have survived longer than some of their eastern counterparts, but they seem to be mentioned more often.

Caer Gloui - Glevum (with Caer Baddan and Caer Ceri)

To the south of Pengwern lay the Romano-British cities of Caer Gloui (Roman Glevum, modern Gloucester in Gloucestershire), Caer Ceri (Roman Corinum, modern Cirencester in Gloucestershire) and Caer Baddan (Roman Aquae Sulis, modern Bath in Somerset). The colonia of Gloucester was founded by Rome around the start of the second century.

It is known that small kingdoms existed here in the sixth century, although their names are not known. Ambrosius Aurelianus, strongly linked to the south west, also seems to be linked to Caer Gloui (and the 'three cities' territory), so perhaps this was his main base. It seems highly possible that the later splintered kingdoms were a single political entity in his time, and were subsequently handed out between descendants (Nennius calls the region Guenet).

In fact, the centre of Ambrosius' power in the mid- to late-fifth century can only lay in one of two places, and of those, Caer Celemion seems less likely. The three cities territory, lying in central Wiltshire, west of the hinterland of the Saxon Shore, and extending from upper Somerset to Gloucester was an area not yet remotely threatened by Cerdic and his people in Hampshire.

And here, strategically situated in the Avon valley, almost due south of the central section of East Wansdyke at Wodnesgeat, some fourteen miles away across the Vale of Pewsey, is Amesbury, which in a charter of about 880 was spelt Ambresbyrig, 'the stronghold of Ambrosius'. Nowhere could be better suited to be the focus of Ambrosius' operations.

According to archaeological evidence, Caer Ceri continued as a centre for civic life in the 440s; the defences were repaired, flood prevention work was carried out on one of the gates, and the piazza of the forum was kept clean. But in 443 the whole Roman world was swept by a plague, the severity of which has been compared to the Black Death, and this hit Britain in around 446. At the same time as the Anglo-Saxon mercenaries in the east revolted, unburied bodies were to be found in Caer Ceri's streets, and the town seems to have contracted to some small wooden huts inside the amphitheatre.

The Romano-British must have recovered from the mid-century plague. The next major event for the territory was Ælle's attack on Mons Badonicus in circa 496. The route the Saxon forces took was probably westwards along the upper Thames Valley and through the Goring Gap.

It seems creditable to assume that the north-facing "Wansdyke", constructed in the fifth or sixth centuries (and which roughly follows in part the proposed upper section of Caer Baddan's eastern border where it leads to the northwestern border of Caer Celemion), was put up by sub-Roman forces in Wiltshire in the face of just such a threat.

It could either have been constructed to ward off this very attack from the direction of the Thames Valley (and perhaps channel the attackers towards Badon), or in response to it, to ensure that no future attacks of this nature could take place. In that it was very effective, until the West Seaxe conquered the heart of Wiltshire in 552.

No doubt greatly heartened by their victory at the end of the century, the sub-Roman presence continued to hold out. For much of the early sixth century (at least until 534, and maybe as late as 560) they remained in general unmolested.

In 577, the West Saxons set great store by the fact that the final kings of the three cities were killed fighting them at the Battle of Dyrham (Gloucestershire). The territory was taken over by the Hwicce, who apparently merged with the existing Briton population. The West Wansdyke region of Caer Baddan seems to have remained in Dumnonian hands (or those of Glastenning) until 597-611, when it fell to the West Seaxe.

Eastern Dumnonia

On Britain's south coast, the modern Dorset area remained in British hands until at least the mid-seventh century.

Given the dominance of Dumnonia over the whole of the south west, it is unlikely there was an independent kingdom here, but either Caer Durnac (Roman Durnovaria, Dorchester in Dorset - from the former Durotriges tribe of this territory) or Wareham (the site of several early British memorial stones) may have hosted a regional power base, or sub-kingdom.

Its name is unknown but extrapolating from Dorset's modern name, and the fact that Saxon settlers in the area called themselves the Dornsaete, the name Dorotric, or Dortrig, is not impossible. Defnas (Devon) has also been used for the neighbouring area to the west, probably to indicate the Britons there.

Ceint (Cantiacum/Kent)

Nothing outside of the traditional story of Vortigern's betrayal by his Jutish foederati is known of post-Roman Kent. It cannot have remained a free territory for more than a generation before being captured by Hengist and Horsa between 450-455.

They were given land there in 450, and began their revolt later the same year. But Ceint was definitely a British kingdom in 450, and may have been established by the time Vortigern became High King in around 425. Its capital would have been Durovernum (Canterbury).

The story of its capture ascribed a King Gwyrangon as its ruler. Doubtless he became one of Vortigern's staunchest detractors when he found the High King had given his kingdom away to barbarians, but he must have put up a fight. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle depicts two major battles, Agæles threp (Aylesford in Kent) in 455 and Crecganford (Crayford) in 456, before the British are said to have given up on Ceint and retreated to London. One further defeat sealed Kent's fate.

Linnuis (Lindum/Lincoln)

The colonia of Linnuis, or Lind Colun, was founded by Rome around the start of the second century with the name "Lindum colonia".

The possible post-Roman kingdom of the same name was linked to the Lincolnshire region, and the names are remarkably similar, given the translation from Celtic to English. Linnuis appears in Nennius' list of Arthur's Twelve Battles, making up four of them.

These battles were fought one after the other, suggesting a series of strategic fights, or a running battle along one of Linnuis' rivers (Dubglas, the modern River Trent?). The aim must have been to push back an Anglian incursion, or a large scale Saxon raid. There were already Anglians settled in Deywr, on the other side of the Humber, although they appear to be mostly peaceful at this time.

On the other hand, the Saxons to the south were actively hostile, and the Historia Brittonum describes how, at "...Hengist's death, Octha his son went from the northern part of Britain to the kingdom of Kent".

Hengist died in 488, during the presumed height of Arthur's reign, so in theory Octha could have been recalled from an attempt to take territory in Linnuis.

The probable Celtic name of the capital of this region is Caer Lind Colun (modern Lincoln, Roman Lindum colonia, hence Lind(um) Colun(ia)). The name Linnuis would also appear to derive from that of the regional capital.

Linnuis appears to have be taken over early by the Anglian Lindiswaras from the region of the Humber, in circa 480 AD (perhaps as a result of territory ceded during the attacks postulated above?). That much is about all that is known in an area that was greatly isolated from the country by the extensive marshlands around The Wash (Metaris Aest.) to the south, the vast Sherwood Forest and the marshes of the River Trent to the west, and the Humber to the north.

Nothing is known of the Anglian Kingdom of Lindsey until the late eighth century, but it is possible that the Linnuis section of the Saxon Shore passed to them intact, and may have included some intermarriage between Angles and Romano-Britons.

Archaeological finds of British and Anglian pottery at the same site in a Saxon church at Barton-on-Humber supports the theory that there was no break in rule between British and Anglian governorship of Lindsey.

Ynys Weith (Inis Vectis - Wight island)

The Isle of Wight, or Inis Vectis, was either Romano-British until 530 AD, when it was conquered by the West Saxons, or it was seized much earlier by the Meonware Jutes from Hampshire, and the date of 530 is a later invention by the West Saxons.

While it was still British, however, it may have fallen under the control of Caer Gwinntguic, probably as a sub-territory, as became the accepted practise after the collapse of Roman authority. The Romano-British name of the military structure from which the island was governed is not known.

--------------------------------------------------------------------

Last but not least, I want to remember that sixty miles west of the Wight island -on the coast surroundings of modern Dorchester- there was the sub-roman settlement of "Durnovaria". This area remained in Romano-British hands until the end of the 7th century and there was continuity of use of the Roman cemetery at nearby Poundbury until the end of the next century. Dorchester has been suggested as the centre of the sub-kingdom of "Dumnonia" or other regional power base, that had some commerce with continental Europe.

Tintagel castle in Dumnonia is worldwide known as a possible link to the famous "King Arthur": in 1998, the "Artognou stone" was discovered on the island, demonstrating that Latin literacy survived in this region after the collapse of Roman Britain.

In 1998, this "Artognou stone", a slate stone bearing an incised inscription in a "modified" Latin, was discovered on the Tintagel island, demonstrating that Latin literacy survived in this western region during the Sub-Roman years and that probably the Romano-Britons of the region used a romance language (the "British Latin": read for further information https://web.archive.org/web/20140821232929/http://www.mun.ca/mst/heroicage/issues/1/hati.htm) for some centuries after the Roman legions departure.

Furthermore, in a village near Durnovaria archaeologists have found evidences of a limited Romano-Britons presence until the second half of the eight century: the oldest "testimony" of Sub-Roman Britain!. Click on the following map showing the village near Southampton:

Indeed the four centuries of existence of Roman Britain (until 410 AD) were followed by nearly four centuries of "diminishing" existence of Sub-Roman Britannia. The most dynamic urban activity of Sub Roman Britannia happened in the city of "Viroconium" (Wroxeter). Philip Barker's meticulous excavations of the baths basilica site revealed the constant repair and reconstruction of a Roman masonry structure into the mid fifth century. At that point, a large complex of timber buildings was constructed on the site and lasted until the late sixth century when they were carefully dismantled. Described by the excavator as "the last classically inspired buildings in Britain" until the eighteenth century, this complex included a two-storied winged house--perhaps with towers, a verandah, and a central portico--smaller auxilliary buildings (one of stone), and a strip of covered shops or possibly stables. More a villa than a public building, it was perhaps the residence of "tyrant" like Vortigern who had the resources to build himself "a kind of country mansion in the middle of the city" with stables and houses for his retainers.

Viroconium is estimated to have been the 4th-largest Roman settlement in Britain, a civitas with a population of more than 15,000. This important Romano Briton settlement probably lasted until the end of the 7th century or the beginning of the 8th (according to White and Dalwood; please read page 5 of their famous "Archaeological assessment of Wroxeter, Shropshire": https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archiveDS/archiveDownload?t=arch-435-1/dissemination/pdf/PDF_REPORTS_TEXT/SHROPSHIRE/WROXETER_REPORT.pdf).

Finally I want to pinpoint the existence of some isolated villages called "vicus" -in central and north Britannia- where Romano-Britons maintained their identity for some centuries (Sub-Roman Britain lasted nearly 4 centuries, from 410 AD to approximately the second half of the 700s), even if totally surrounded by the Anglo-Saxons: for example, just south of the Hadrian Wall there were a few "vicus" near Piercebridge Roman fort that possibly lasted until the 700 AD (read http://www.yorkshireguides.com/piercebridge_roman_fort.html) with a Roman bathhouse. Even in this case the reader can click on the bottom map to see the Piercebridge "vicus" in the year 700 AD:

.jpg)