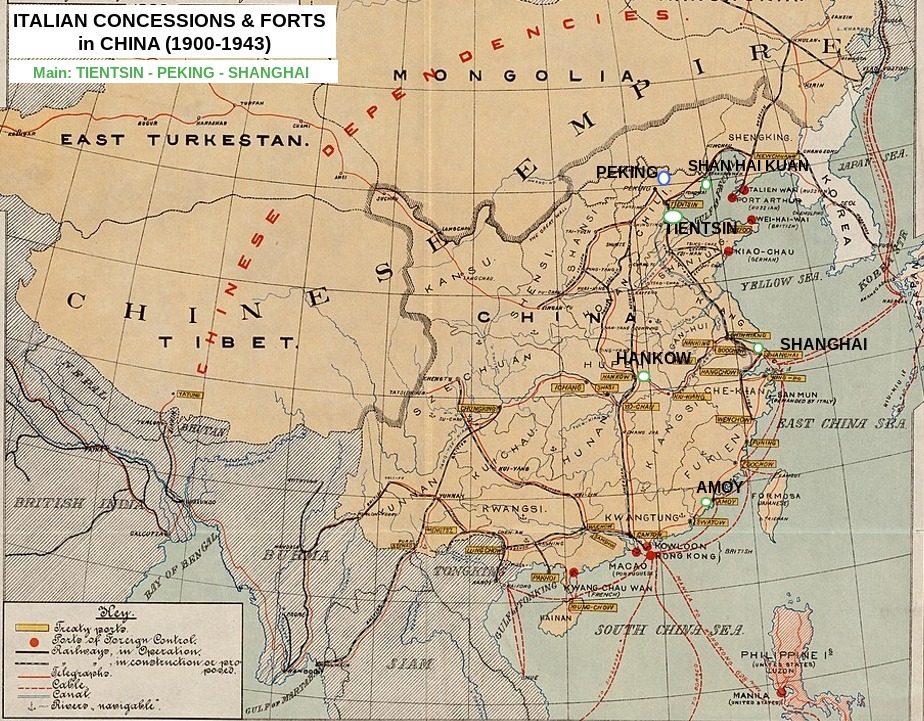

During its short colonial history, Italy occupied several African territories such as Eritrea, Somalia, Ethiopia and Libya: rather vast and interesting dominions. It is lesser known, on the contrary, the story of another small and far colony in China: Tientsin (a town ca. 200 km south of Beijing) and the so-called commercial quarters of Shanghai and Beijing (under the direct sovereignty of Rome as from 1901, after the failed Boxers' revolt), two small Italian enclaves inside the Chinese state, which hosted Italians as well as larger English, French, Russian, German and Japanese territories since the end of XIX century. Additionally, there were also a few forts and commercial places under Italian control.

Map showing the Italian concessions & forts in China. Additionally there were (but together with other colonial powers): Taku (fort with Great Britain) and Beihai (port with only commerce rights). However Italy had full colonial controls only in the Tientsin concession

Seven locations & one treaty port

Italy in the first half of the 20th century has had concessions in Peking, Tientsin, Shanghai, Amoy and Hankow with two forts (Shan Hai Kuan and TaKu). However it is noteworhy to pinpoint that only in Tientsin, Peking and Shan Hai kuan, the italian government was in control (with colonial property rights). In the other locations Italy was united (or affiliated) with other colonial powers - like with Great Britain in the Taku forts.

There was even the Treaty Port in Beihai (southern China), that was allowed to have a small area for Italian commerce.

History

It all started with the "Boxer rebellion" and consequent war of the Boxers & China against the "eight powers"(Great Britain, France, Italy, Austria-Hungary, Germany, Russia, the United States and Japan).

THE BOXERS REBELLION:

On 20.4.1900, the so-called "war of the Boxers" began (the members of a secret society with a xenophobic orientation were so called). In Pao-Ti-Fung, in fact, a first bloody battle developed between gangs of insurgents and a community of missionaries and Chinese converts to Christianity (as such, considered bearers of Western culture). The clashes spread in a very short time and immediately the main powers sent their ships to Taku (port near Tien-Tsin) to land units of sailors. The command of the operations was assumed by the British Admiral Seymour. At that time only Elba and Calabria were found in Italy for Italy; both landed a group of 40 sailors (the former under the command of T.V. Paolini and the latter under the command of T.V. Sirianni) who together with other allied contingents headed, respectively, for Peking and Tien-Tsin to protect the existing Legations. After these moves the Allied strength at Peking reached 428 men and at Tien-Tsin 402 men. It was therefore a small force that could be reinforced with another 950 men or so who could be unloaded from ships already existing on site (without affecting their operational efficiency); of these, about 20 men could still be taken by Italian ships. Shortly after the situation worsened and Adm. Seymour then decided to land the rest of the available men as well; from the ship Elba therefore landed another 20 sailors who, under the command of the S.T.V. Carlotto, were sent to Tien-Tsin. In the meantime, the ships of the great powers continued to arrive at Taku with a relative influx of new contingents. Thus, on 10.6.1900, Adm. Seymour decided to resign marching towards Beijing in command of a column of 1782 men which also included 20 Italians. A few days later (June 17), an allied force made up of 5 gunboats of Russian, German and French nationality (on which a group of 24 Italian sailors under the command of the S.T.V. Tanca had also been embarked) instead conquered the forts of Taku in order to ensure the free connection between allied ships and troops on land. In response to the loss of Taku's forts, the Boxers, who already occupied the walled city of the Chinese quarter of Tien-Tsin, attacked the Legations located on the European side of the city and it was therefore in this phase that the death of S.T.V. Carlotto (this was the first of our fallen in the Boxer War; later, for various causes, another 64 Italian soldiers died). Thus we arrived at 26 June when Adm. Seymour, unable to reach Beijing due to the great numerical superiority of the insurgents and the continuous clashes with the latter (in which five of our sailors died), made his return to Tien-Tsin (where in the meantime the city had also fallen into the hands of the allies Chinese wall). At the same time, the news arriving from Beijing was increasingly dramatic. On the allied side (in the meantime reinforced by the arrival of new contingents of infantry) it was therefore decided to intervene by sending an expeditionary corps from Tien-Tsin. To this end, a contingent of land and sea troops was set up, armed with 70 cannons, divided into two columns: one by Japanese, English and Americans (about 12,700 men) who had to follow the right side of the Pei-ho river and the other by Russians, French, Germans and Italians (about 5,000 men, among which the Italians were 35) who had to follow the left side of the river. These men set out on August 4th. Meanwhile in Beijing the Legation Quarter had been subjected to a massive siege with continuous bombings by the Chinese; on June 21st the Belgian and Austrian legations went up in flames and on the 22nd it was also the turn of the Italian one. The fighting between a few defenders of various nationalities and the hordes of insurgents who launched themselves in waves to attack the defense lines of the Legation quarter succeeded each other more and more bloody throughout the month of July and in the first two weeks of August until, on 14 August , the contingent departed from Tien-Tsin arrived at contact with the enemy by subjecting him to shelling. It was the column made up of Japanese, English and Americans as the one made up of Russians, Germans, French and Italians had been forced to return to Tien-Tsin after only two days of march being essentially made up of sailors with little training in the long run marches; this second column was in any case immediately replaced by another made up of infantry elements (which in any case also included the Italian sailors under the command of Ten. Sirianni) which arrived in Beijing when the liberation was now complete. In a few hours the troops allies breached the city walls arriving near the imperial palace and forcing the Empress to flee (15.8.1900); thus ended the siege of Beijing, which lasted 55 days. In that famous event, the losses of the allies were 63 dead, of which 13 were Italians.However, the conquest of Beijing was now a fait accompli and therefore the use of the new arrivals, not only Italians but also of other nationalities), was destined for other areas that had until then remained at the mercy of the insurgents, from where news of massacres of missionaries and local Christians. Although often in uncoordinated formations, the various contingents began a series of operations to restore order and normality in places still marked by turbulence. The main operations in which the Italian units were engaged were: - from 9 to 12 September : an expedition to Tu-Liu. From this location, it was feared that a Boxer attack on Tien-Tsin might be launched. Of our expeditionary corps, 350 bersaglieri and 600 men of infantry took part. - From 19 to 21 September: the occupation of the forts of Pei-Tang. Around 1,000 Italians took part together with the allies. - From 29 September to 2 October: occupation of the forts of Chan-ai-Kouan. For Italy, 330 Bersaglieri and 140 sailors.-October 12 to 19: occupation of Pao-ting-fu. The operation was conducted by forming two columns of international troops: the one coming from Tien-Tsin included 358 Italians while the one leaving Beijing included 516 Italians.-3/ November 4: Cu-nan-shien is occupied. The action was conducted under the command of Col. Garioni and around 170 Italians took part. - From 12 to 26 November: expedition to Kalgan. 599 Italians took part in the occupation of the city and other neighboring localities. Thus we arrived in the middle of winter, with temperatures that often reached 10 degrees below zero. Nonetheless, our troops took part in numerous expeditions whose purpose was to quell in the bud the outbreaks of tension or to punish small armed bands operating in the area. The main actions of this kind were carried out at Er-lan-ciuan; Tung-Hi; Ma-fang-tshwange Ping-Ku-shien. After these operations the situation moved towards normality. The peace definitive text was signed in Peking on 09.07.1901. The Boxer War was therefore officially over.

Photo of some soldiers of the "Eight powers" (from left: Britain, United States, Australia, India, Germany, France, Austria-Hungary, Italy, Japan. Australia and India were under Britain control), but without Russia

The history and the vicissitudes of those eastern settlements, which remained under the Italian dominion for nearly half a century, involved not only the diplomatic representatives and the few Italian colonists but also the forces of the Army and the Navy. The larger part of about Italian 20,000 soldiers and officers who fought in the victorious campaign (June-August 1900) against the Boxers' rebel Chinese nationalists troops - allied to the United States, Great Britain, France, Austria-Hungary, Germany, Russia and Japan - were recalled from Beijing after the end of the conflict. One year later, the signing of the peace treaty between Empress Tsu Hsi and the colonial powers (7th September 1901) made Italy the right to occupy a portion (nearly one square kilometre wide) of Tientsin and two commercial quarters in Beijing and Shanghai (it was temporarily enlarged in 1927 with the addition of the former Austro-Hungarian concession)

The Savoy government decided to implement the growth of missions, communities and commercial companies in those new settlements by sending diplomatic attachés and one special military force in charge of the protection of those tricolour territories. In 1915, when Italy entered the war alongside the Central Powers, the colony of Tientsin counted about 10,000 inhabitants (Chinese) and 350 to 400 Italians, most of whom were traders. At that time the defence of the settlement was entrusted to only ca. 200 soldiers and officers (mostly Bersaglieri) supported by a special battalion (composed by Austro-Hungarian POWs of Italian origin captured in Galizien by the Imperial Russian troops and then released and transferred by train to Far East to reinforce the Italian garrison in China) and by some fifty Chinese militiamen. A few years later, when the war ended, the government of Rome finally decided to strengthen the garrison with a well-armed and trained intervention force. On 5th March 1925 the Battaglione Italiano in Cina was ready to be shipped to China. It was a very skilled unit, mostly composed of soldiers of the elite Reggimento San Marco. The battalion was quartered in the new barracks named Ermanno Carlotto and consisted of three companies of 100 men each: the San Marco Company, the Libia Company and the San Giorgio Company

On 18th April 1928, the San Marco Company was inspected by the former Chinese emperor Pu-Yi during his visit in the Italian settlement. At the beginning of 30s, the Italian colony began to steady, also thanks to the good diplomatic relationship set between Rome and Beijing and also to the improvement of the trading and technical exchange set up between the two countries (the Chinese government even entitled two Italians, Gibello Socco and Evaristo Caretti, respectively for the direction of the Ministry of Railways and the Ministry of Post). Tientsin as well as the Italian quarters of Shanghai and Beijing had quite a serene period during the first half of 1930s, characterised by a fairly good commercial town planning and entrepreneurial growth. With the arrival of Mussolini's son-in-law Galeazzo Ciano appointed secretary at the Beijing's legation and then minister plenipotentiary in Shanghai this process further improved, together with the relationship between Rome and the new Chinese leader Chiang Kai Shek. In particular, Ciano became close friend with a leading exponent of the Chinese nationalist's military elite, especially with Marshall Chang Hsueh Luang a true admirer of the Mussolini's fascist regime. In 1932, soon after the Mukden's accident (the first act of Japan's clear hostility against China) to prove once more the friendship towards Italy Chiang Kai Shek choose Ciano as a go-between with the Japanese representative. In 1932 - under Ciano's pressures for creating an even stronger economic and military alliance between China and Italy the Italian shipping company Lloyd Triestino opened a new service linking Italy to Shanghai by scheduling on that route two modern transatlantic vessels, the Conte Biancamano and the Conte Rosso (which immediately settled a speed world record of only 23 days during the first voyage). With this new service, supported by those ones of other companies employed in the trade of various goods and products, the economic exchange between Italy and China reached such good levels to alert Great Britain and France

It was in that period that Italy started to provide Beijing with military aircraft. After he presented Chiang Kai Shek with a three-engined Savoia Marchetti, Mussolini sent to China a huge delegation of pilots, engineers, technicians and trainers to convince the Nanking's government and the young Chinese aviation's representatives to purchase Italian military airplanes and to accept the survey for the creation of factories to build on purpose licensed models offered by Rome. The Italian aeronautical delegation , commanded by General Roberto Lordi and composed by renown aces and test pilots such as Valentino Cus and Mario Bernardi (become famous thanks to his speed record of 700 km/h set by his special Macchi hydroplane) did not succeed in its goal. The Chinese government decided in fact to purchase only a small number of Fiat CR32 and some bomber-reconnoitres Caproni Ca101, Ca111 and Ca133. On 6th November 1937 when Italy joined the Anticomintern Pact - the relationship between the two countries suddenly changed. Mussolini, by signing that agreement, got close to Tokyo, opening a series of good exchanges with powerful Japan, which in the meantime had become the worst enemy of weak Nationalist China. It goes without saying that Chiang Kai Shek did not like at all this decision and broke off any relationship with Rome.

Magazine image of the Italian troops ("Bersaglieri") conquering a fort in China in 1900

The new situation caused the immediate isolation to the Italian colony of Tientsin and the quarters of Shanghai and Beijing, which felt immediately hostility from all around. The military responsible of the colony and the Partito Nazionale Fascista's representatives (at that time in China the party's secretary was Carlo Fumagalli) realised soon the dangerous situation, considering the insufficient Italian forces set to defend the garrison. They immediately demand from Rome for an urgent supply of men and warships. This request even if it was dealt with a small quantity was fulfilled in quite a short time, but unfortunately not before the war between China and Japan broke out. Some months before, in July 1937 - when the first fights had started between Japanese and Chinese troops - Commander Bacigalupi of the gunboat Lepanto had got in charge of the first Italian defence detachment, composed by part of the Ermanno Carlotto's and Lepanto's crews. The Tientsin based Battaglione Italiano in Cina joined soon to these forces. A few months later when the well-trained and combat hardened Japanese armies had spread out the Chinese territory - the Italian Comando Supremo decided to send more forces (some hundreds of soldiers) and the light cruiser Raimondo Montecuccoli to Tientsin. This cruiser sailed from Napoli on August 27th and arrived to Shanghai on September 15th, just to coincide with the first Japanese air bombings on the town. By then, at least what with 1,200 Army's and Navy's soldiers were in China to defend the safety and the interests of its 500 to 600 resident compatriots.

On the whole, in 1937, in Tientsin and Shanghai there were stationed 764 men with officers and soldiers of Battaglione Granatieri di Sardegna arrived by ships from Massaua (Eritrea). Part of these effectives supported the English (2,500 men) and the American (1,400 men) contingents who were already in Beijing and particularly in Shanghai to protect the Anglo-Saxon citizens (in Shanghai there were 308 American civilians, 971 English, 199 Germans, 654 Japanese, 182 Russians and 42 Italians). On September 27th and October 24th, some Japanese bombers Mitsubishi attacked the Italian light cruiser Montecuccoli during a raid against Shanghai. During these two missions was the Italian vessel hit by splinters and had one dead and several injured (the accident compromised seriously the diplomatic relationship between Rome and Tokyo).

Foreign Troops (1933) in Shanghai : British Forces: 2,160; French Forces: 1,982; Japanese Forces: 1,934; U.S. Forces: 1,758; Italian Forces: 108 (https://www.worldstatesmen.org/China_Foreign_colonies.html)

On August 6th 1937, the Italian Comando Supremo decided to move 30 soldiers stationed in Shanghai and Hankow to protect the local Italian consulate. This small group was transferred to its destination from the Montecuccoli, which definitely left China for Italy on August 29th. On December 23rd the cruiser was replaced by its sister vessel, the light cruiser Bartolomeo Colleoni, which stood in defense of the Italian garrisons in China until 5th September 1939, when it was called back to Italy due to the Second Conflict's outbreak. In the same year, part of the contingent (composed also by effectives of Air Force, Carabinieri and Guardia di Finanza (i.e. Revenue Guard Corps)) was repatriated, leaving to the garrison part of the weaponry and two small naval units (the gunboats Lepanto and Carlotto in Shanghai and Tientsin).

After the Italian declaration of war (10th June 1940), the Navy's Comando Supremo ordered to some Massaua-based units to sail to Far East. This decision was made due well-grounded fear that in case of fall of the East Africa Empire, the English could have had the chance to get hold of the Italian ships. Thus, in February 1941 (less than two months before the British capture of the Massaua's base) the colonial ship Eritrea (armed with four 120 mm, two 40 mm guns and two 13.2 mm machine guns) and two armed vessels (Ramb1 and Ramb2: two modern and fast banana-carriers converted into auxiliary cruisers by the equipment of four 120 mm guns and some anti-aircraft 13.2 mm machine guns) sailed to Kobe (Japan) and, in alternative, the ports of Shanghai and Tientsin. While the Eritrea and the Ramb2 reached their destination, avoiding the patrolling of the Royal Navy, the Ramb1 met off the Maldives Islands with the New Zealand light cruiser Leander, by which it was sunk.

Between March 1941 and September 1943 the Italian concession of Tientsin and the consulates of Shanghai, Hankow and Beijing lived a quite peaceful period, in spite of the not optimal relationships with the Japanese occupation military Command. This last one, in fact, did not like the presence of Europeans - even if Japanese allieds like the Italians - in the government of towns or even quarters located in their zone of influence. Notwithstanding this, the Italian military attaches and diplomats in China and Japan tried to lower as much as possible the reasons of friction, even when Tokyo forbade to Eritrea and Ramb2 to carry out offensive cruises against the English fleet in the Pacific Ocean (the Japanese, at least until 7th December 1941 - date of the unexpected attack to Pearl Harbor - did their utmost in order to avoid whichever embarrassing situation with USA and Great Britain). Only after Japan's official entering in war, Eritrea was allowed to lend support to the Italian oceanic submarines reaching Penang and Singapore from the far base of Bordeaux, loaded with strategic products and goods destined to the Japanese industry of war. Concerning the many Italian cargo ships which were within Chinese and Japanese water when Italy entered the war allied to Germany against Great Britain and France, most of them (such as the large steamer Conte Verde) remained unemployed or had to perform voyages for the Japanese, while some others tried to reach the French coast (Bordeaux), by breaking the British blockage. Some of these latter succeeded in their goal, carrying to Europe quite good quantities of strategic cargoes (rubber, quinine, tin).

Tuesday, April 4, 2023

Friday, March 3, 2023

ADDIS ABEBA ITALIANA (1936-1941)

ITALIAN ADDIS ABEBA (1936-1941)

The following is an essay about Addis Abeba (the capital of Ethiopia) when was under Italian rule from 1936 until 1941. The essay was written by Bruno D'Ambrosio of the University of Genova (Universita' Statale di Genova - Italia):

ADDIS ABEBA ITALIANA

Map of Italian Plan for Addis Abeba marketplace site: (1) Italian City; (2) Natives' City. Original in "Gli Annali Dell'Africa Italiana". Anno II -Numero 4 -1939 -XVIII

On 5 May 1936, Italian troops occupied Addis Ababa (usually called Addis Abeba) during the Second Italo-Abyssinian War, making it the capital of "Italian East Africa". Addis Ababa was governed by the Italian Governors of Addis Abeba from 1936 to 1941 (https://www.worldstatesmen.org/Ethiopia.html#Italian-East-Africa). In those five years the Italian government made many improvements to the city, from the construction of Hospitals and roads to the creation of stadiums like the Addis Abeba stadium (www.artefascista.it/adis_abeba__fascismo__architettur.htm).

Indeed in less than three years (1938/1940) -after the arrival of the Viceroy Amedeo D'Aosta and the first successes against the Ethiopian guerrilla (called "arbegnocs") with the complete "pacification" of the region (called "Scioa" and sometimes "Shewa") around Addis Abeba- there was in the city & surroundings:

1) a rapid increase in public works, 2 the construction of an extensive road network with six thousand kilometers of paved roads, 3) a visible improvement of agriculture and veterinary services, 4) the construction of clinics and (previously non-existent) health care places located every thirty kilometers, 5) an appreciable spread of education and various forms of assistance and 6) a generalized development of Italian entrepreneurship and work.

The first radio broadcasts in Addis Abeba & Ethiopia were created in 1937, when many radio-programs were done in Italian language for the Italian colonists

The Ansaldo Corporation of Italy in 1935 created a one-kilowatt station in the outskirts of Addis Abeba, inaugurated with a speech of emperor Selassie. The Italians took over the station in early 1936 and planned to develop it into a communications center for their new empire, joining those already established in Somalia and in Asmara (Radio Marina). A more powerful radio station of seven kilowatts was started by the Italians in 1937 (broadcasting the first radio-programs of Ethiopia, as can be seen in the above photo).

The Bank of Italy issued the loan "City of Addis Ababa" for 200 million lire, and in the spring of 1940 the city appeared to be a huge construction site with big investments done by the italian government. When Italy entered the war in 1940, the attack on British Somalia in the summer of 1940 and the British counter-offensive in early 1941 blocked all the works of Addis Ababa.

The news of the construction of the new capital disappeared from the Italian press after the end of WW2, as nearly all the traces of the Italian occupation were later canceled from the current city.

Aerial view of the Addis Abeba center in the urban masterplan of 1939 Italian Ethiopia

Mussolini promoted the development of Addis Abeba: he spent 53 billion current lire for the war and civilian building projects in Ethiopia. This remarkable sum (no other colonial power had spent so much money on the colonies, and in such a short time) reached over 10 % of Italy's GNP in 1936, the year of greatest expenditure.

It is noteworthy to pinpoint that in 1940 there was a satisfactory management -by the Italian government- of relations with different religious cults and that in Addis Abeba (and Ethiopia) there was the construction of churches and mosques without problems.

The Italians favored the development of catholicism in Addis Abeba, also between the ethiopian natives. They enlarged and improved the Cathedral of Addis Abeba.

BRIEF HISTORYbr/>

Map showing the Italian conquest of Addis Abeba and Ethiopia in 1935-1936

The city of Addis Abeba was conquered by Italian troops in 1936 and soon was declared the capital of the new Italian empire.

Addis Abeba grew from 45,000 inhabitants in spring 1936 (when the Italians won the Italo-Ethiopian war) to nearly 150,000 in spring 1941, when the Italians were defeated and the Allies (with emperor Selassie) returned to the city.

The city, that looked in 1935 like a medieval town (also because of thousands of slaves living in dire conditions) in just five years was transformed in a modern capital where more than 40,000 Italians lived in a city with a typical XX century society, free of slavery and full of developments & improvements.

Indeed during Italian rule, the Italians abolished slavery in all Ethiopia, issuing two laws in October 1935 and in April 1936 by which they declared to have freed 420,000 people. After Italian defeat in Second World War, Emperor Haile Selassie, who returned to power, abandoned his previous ideas about a slow and gradual abolition of slavery in favor of one that mirrored Italy’s civilized abrogation (abolition-of-slavery-in-ethiopia)

Italian propaganda postcard showing the freedom from slavery of Ethiopians by the Italian troops of the "Divisione Sabauda" in 1935

So, the first thing the Italians did in the just conquered city was to proclaim the end of slavery and to make free nearly 10,000 slaves in the Scioa region.

The british Lady Kathleen Simon of the "Anti-Slavery Protection Society" was one of the first to appreciate this action and the definitive end of slavery in Ethiopia.

Indeed in Addis Ababa the situation was full of expectatives after the Mussolini proclamation of the "Italian Empire" in May 9, 1936. The capital of the empire was due to become, in Mussolini’s opinion, the most beautiful and futuristic city in Africa, the beacon of the new fascist civilization. The preparation of the new town planning scheme was very long and problematic, involving top professional people like Giò Ponti, Enrico Del Debbio, Giuseppe Vaccaro and even Le Corbusier, who personally asked Mussolini to be allowed to design the plan for the new city (Le-corbusiers-visions-for-fascist-addis-ababa/).

However the city in May 1936 had no major infrastructures: there was no electricity in many areas, there were no sewers at all, only a few roads were asphalted and the city lacked a road network connecting with other Ethiopian urban centers. But there was an aqueduct in operation, which supplied only some areas, while fast transport was provided only by the Gibuti-Addis Ababa railway line, built by the French and inaugurated in 1917. The Italians solved all these infrastructure problems in a few years of hard work!

The famous "Villa Italia" in the outskirts of the city was improved in late 1936, as a residence of the main Italian authorities ( https://baldi.diplomacy.edu/diplo/texts/Del_Papa_VillaItalia.pdf).

In autumn 1937, the result of the initial works managed by the Governorate of Addis Ababa in a year and a half of activity was, all in all, positive: the repaving of the main roads, the restoration of existing health facilities, the expansion of some hotels and the restructuring of the natives market. Moreover six buildings of the I.N.C.I.S ( housing institution for government employees) were built. And also the "Casa del Fascio", both inaugurated on 28 October; while the Regulatory Plan Office had expropriated property in the industrial zone and some areas had been given in concession to institutions and private individuals.

Video of initial Italian constructions in 1936 Addis Abeba:

However work started on a full scale only in 1939. The fourth and last definitive Addis Abeba urban plan -approved by Mussolini- provided for a clear separation between the European and indigenous areas. This would have meant transferring the African population and building tens of thousands of new homes.

Indeed the definitive Urban Plan for Addis Abeba was approved by Mussolini in late 1938 (with the "green" separation of the native southern quarters from the Italian northern quarters), but was never fully created, because of WW2.

After the conquest of the city, some Ethiopians started a guerrilla war with terrorism in all Ethiopia and many italian and eritrean soldiers were attacked and sometimes murdered even in Addis Abeba. In February 1937 -after nearly 200 Italians and Eritreans (including women) have been attacked & murdered by the "arbergnocs" in the city's area- happened the attempted assassination of Marshal Rodolfo Graziani, Marquis of Negele, Viceroy of Italian East Africa. As a consequence the Italians did a massacre of suspected Ethiopians and since then the city was fully "pacified" until the british conquest in 1941.

Because of the complete lack of terrorism in Addis Abeba, many Italian colonists settled in the city after 1937 and the city flourished in an astonishing way: Italian settlers had increased from a few thousands in early 1937 (with 150 families) to over 40,000 in March 1940 (33,059 men, 6,998 women and about 4,000 families) whilst the African population had practically doubled and was estimated at about 100,000 people.

When started WW2 Addis Abeba was a capital with nearly 150000 inhabitants and looked more like a busy european city with a booming development than a lazy african colonial city.

Furthermore ut is noteworthy to pinpoint that the "Health Corps" of Italian Africa was created only in 1936, and it was made up of about 200 doctors and health inspectors, by organising a special public competition which took place between 1937 and 1938. Three centres were gradually built in Addis Ababa, Asmara and Mogadishu, specialised in the cure of malaria, as well as numerous hospitals and clinics. Following direct orders by Mussolini, since 1936 special attention was naturally given to the prevention and cure of venereal diseases (since the authorities could not prevent contact between Italian men and African women), by rounding up and imposing forced hospitalisation on thousand of native women in special “syphilis homes”.

As a consequence towards the end of 1938 the incidence of sexual diseases had dropped: the percentage of Italian soldiers suffering from venereal diseases was about 5 % compared to 10 % in 1937, whilst that of civilians, which was much lower, had decreased from 1.4 to 0.9 %. An improvement was also registered among indigenous military personnel, from 3.7 % to 2 %. These data of course reinforced Mussolini’s will to increase the number of whole families emigrating from Italy to AOI. A remarkable effort was made to improve healthcare: beside the doctors belonging to the Italian Africa Health Corps, flanked by 450 military doctors, there were about 500 civilian doctors (232 specialists, among whom 30 paediatricians, and 262 general practicioners). Special maternity wards were built in the hospitals situated in the main locations.

The new Italian hospital in Addis Ababa had a delivery room and a pediatric clinic for Italians, with a capacity of over 100 beds in its various sections: expectant mothers, postpartum mothers, babies’ room, gynaecological ward, infectious diseases, visitors’ room, etc. The children’s hospital was subdivided into separate wards for babies and older children, for infectious, gastro-intestinal or pulmonary diseases, etc. Moreover, a university-type faculty was founded in early 1940 in Asmara to train nurses and the same was planned for Addis Abeba.

In Addis Ababa the number of new-born Italian babies was continually growing, rising from 50 in 1937 to 570 in 1939 and the number of weddings being celebrated shot up too, despite the dramatic housing shortage. Italians lived in all possible ways: many continued to live in temporary shelters (tents, huts and prefabricated houses), whilst a lot of families used indigenous homes that had been expropriated or rented.

Mussolini found this situation intolerable, and he constantly urged the Italian East Africa’s government to ensure a more vigorous policy of racial separation (on his orders the African market had been forbidden to Europeans, but the measure was later withdrawn, because indigenous trade was indispensable for the provision of food by whites).

As Amedeo d’Aosta (the new Viceroy of AOI since 1938) once remarked, the solution of the problem of racial prestige was incompatible with the housing situation: firstly, there was not enough money to build houses for Italians or tukuls in the new indigenous town, then there were huge difficulties in sourcing water and building materials; that is why most Ethiopians, after cashing in their expropriation indemnity, went back to the old quarters.

The 1938 arrival to Addis Abeba of Viceroy Amedeo D'Aosta

To confront the situation, given that, as the Viceroy Amedeo repeated, it was impossible to separate the two races “by evicting one hundred thousand natives”, and whilst waiting for the implementation of a low-cost building programme for the colonists, it was necessary to stop new family units emigrating to Italian East Africa.

To house the families of AOI government employees, who had been forced by Mussolini to take their wives and children to Africa, the national housing body for civil servants (INCIS - "Istituto Nazionale Case degli Impiegati dello Stato") financed the construction of 42 buildings with 119 flats, largely insufficient to satisfy all requests. Private individuals did not have any incentives to invest in residential building save for exceptional cases. Notwithstanding the “winds of war”, only in July 1939 a law was emanated which authorised banks operating in AOI to grant loans and mortgages to institutions, societies or private citizens who wished to build civilian houses (including cheap homes), and the planning schemes of the most important towns were completed only on the eve of WWII.

The war definitely put an end to all works in progress, and today there are just a few traces of the five years of Italian occupation .

But if the new imperial cities had trouble in taking shape, social life in Addis Ababa and Asmara was pulsating just like that of any other European town. At the heart of the city were the markets: in the Ethiopia capital in 1939 over 75,000 heads of cattle had been slaughtered and thousands of tons of foodstuffs had been sold. Dozens of shops and even department stores were opened in the Scioa cities. Leisure activities also boomed: in Addis Ababa four cinemas had been built for Europeans and one for Africans.

New dancehalls, restaurants and bars were being opened everywhere. The working men’s clubs and numerous sports and recreational societies, supported by local government and by the PNF, organised the colonists’ free time. In the Scioa governorate, near the strategic hubs where companies and the army had located their logistic bases, new urban agglomerates rose from scratch, with plenty of restaurants and clubs.

The Italians were the first to promote the football in Ethiopia, after 1937. No overall Ethiopian championship was played in 1938 and 1939, but there were regional leagues in the provinces of Amhara (capital Gondar), Harar (capital Harar), Scioa (capital Addis Abeba) and Galla e Sidama (capital Jimma).

In the Scioa governorate the team participants were made of amateur Italian players -playing mostly in the newly created "Campo Sportivo "Littorio" (video of Littorio's inauguration: http://senato.archivioluce.it/senato-luce/scheda/video/IL5000027374/2/Impero-Italiano-Addis-Abeba.html ), the first football stadium of Addis Abeba. Successively it was enlarged in 1940 (with tribune and athletic lanes). These teams included: Ala Littoria; A.S.A. Citao; Littorio; M.V.S.N.; S.S.Pastrengo ; Piave ; A.S. Roma d'Etiopia-Addis Abeba. However the war stopped these amateur Championships in 1940.

In 1944 the first Ethiopian Championship was held in Addis Abeba, with 5 teams representing the various communities in the capital conquered by the Allies. In the final match the BMME of the British Army won the Fortitudo of the remaining Italian colonists. Participants: St. George (Ethiopian); BMME (British); Fortitudo (Italian); Ararat (Armenian); Olympiakos (Greek).

Italian soldiers paving-asphalting roads in 1937 Addis Abeba center

The Italian Fascist Party (PNF) was a crucial instrument in moulding colonial society in a fascist sense and also in the involvement and training of those Africans destined to fill some inferior role in the civil administration or in the army, through school education and the Gioventù Indigena del Littorio (GIL – the fascist indigenous youth organisation).

Italian colonists’ degree of adhesion to the fascist party was massive, well above the percentage of party members back in Italy, especially among women: at the end of 1939 the PNF had 51,146 members in the colonies, whilst pending applications for membership amounted to 24,397 and those transferred from Italy were 9,950: nearly one third were in Ethiopia (mainly in the capital area). There were 3,308 women enrolled in the fascist organisations (12.8 % of the female population). There also were 237 fascist working men’s clubs with 38,235 members and 106 sports societies with 19,822 members.

Colonisation represented a major turning point in the life of thousands of settlers. The regime conceived a new social plan for the empire, consisting of a society made up by brave and hard-working Italian colonists.

1938 map of the Scioa governorate around Addis Abeba, South of the capital can be seen the "Azienda Agricola Biscioftu" (a huge farm development, with Italian colonists)

Furthermore, since 1937 the peripheral lands around Addis Abeba were improved with colonization projects: the full "pacification" of the Ethiopian guerrilla in the Scioa region allowed in 1938 to start farm projects with Italian colonists.

So, in the same year the O.N.C. ("Opera Nazionale Combattenti") created two modern farms in Olettà, a center about 40 kilometers from Addis Ababa and in Biscioftù, at the same distance from the capital but on the route to Djibouti.

For the valorization of the country around Addis Abeba, other development models were taken into consideration, such as the "capitalist-type colonization" guided by the large private capital (for example, in Addis Alem a factory for the production of slaked lime was established under the Italian management, and in its first year of production it turned out 30,000 hundredweights of the material).

It was considered also the so called "industrial-type colonization", in which the concessionary companies would manage the transformation of agricultural and mining products. Belonging to the latter type was the "Villaggio Torino", designed by Giorgio Rigotti and built about 35 kilometers from Addis Ababa. This was an industrial plant linked to agriculture with a high-rise mill, a pasta factory and a biscuit factory, annexed to which there was a small Italian workers' settlement and an indigenous neighborhood

In 1940 an Italian government study found that there were nearly half a million native Ethiopians (mainly living in the Scioa governorate, where the capital was Addis Abeba) who were receiving salaries from the Italians (in the Army, in the civilian administration, in many private companies and also inside Italian families as maids/nurses/housekeepers): the living standards of the autochthonous Etiopians in these areas increased to levels never historically reached before (G. Podesta, "Emigrazione in Africa Orientale" emigrazione italiana nelle colonie africane ).

After their conquest of Ethiopia, the Italians acted quickly to reorganize the educational system in Ethiopia, that was in a very low level of development (in a country of nearly 6 millions there were only 8,000 students enrolled in twenty public schools in 1935).

A remarkable effort was made to establish a school system in AOI, both for Italians and for Africans. Schools for Italian students were built in thirty locations. Some secondary schools of all kinds were also created in Addis Abeba and in the main Ethiopian towns.

The two most important Italian schools in Addis Abeba were the Liceo-Ginnasio Vittorio Emanuele III and the Istituto Tecnico Benito Mussolini, both reserved for Italian children, while the prewar Empress Menen School for girls was converted into the Regina Elena military hospital. In the city some elementary schools were established for the Italians ( educazione italiana nelle colonie africane ), while also a few new schools were created for the native population: the Italian government pinpointed in 1939 that there were thirteen primary schools in the Scioa governorate, staffed by over sixty teachers and having an enrollment of 1481 Italians & native Ethiopians.

Additionally it is noteworthy to pinpoint that the 512 young Italians enrolled in the "Gioventu Universitaria Fascista" (GUF) in Addis Abeba requested the creation of a university institution in the capital of Ethiopia. In 1939 the GUF asked the government to study this possibility (or at least to allow exams to be done directly in Addis Abeba), but the start of WW2 stopped all this process and the first university in Ethiopia was created only in the 1950s by the French Jesuit Lucien Matte.

Video showing the 1938 welcome to the "Vicere" (Viceroy) Amedeo Savoia-Aosta of Italian Ethiopia in Addis Abeba:

However Ethiopia -and Africa Orientale Italiana (AOI)- proved to be extremely expensive to maintain, as the budget for the fiscal year 1936-37 had been set at 19.136 billion lire to create the necessary infrastructure for the colony. At the time, Italy's entire yearly revenue was only 18.581 billion lire (https://storicamente.org/gagliardi_colonie_italiane_africa_fascismo ).

WW2 put an end to the Italian empire: in April 1941 Addis Abeba was occupied by the British. After signing the surrender, his last italian governor, Agenore Frangipani, committed suicide because was forced to surrender the city to them without fighting - in order to save the lives of the Italian civilians living in Addis Abeba (mainly women and children) from the vengeance of the ethiopian nationalists (the "Arbegnocs", who already had done a massacre with the Italian civilians in the city of Harar, defended harshly by italian troops some days before). Frangipane considered "a lack of honor" for himself the surrender without fighting.

It is noteworthy to pinpoint that after the Italian surrender in Addis abeba, some Italians started a guerrilla war against the Allies, in the hope of a possible Rommel victory in Egypt and with the return of the Axis troops in Ethiopia later.

One of them was Rosa Dainelli, a doctor. She -in August 1942- succeeded in entering the main ammunition depot of the British army in Addis Abeba, and blowing it up, miraculously surviving the huge explosion. Her sabotage destroyed the ammunition for the new British Sten submachine gun, delaying the use of the newly created piece of equipment for many months. Doctor Dainelli was proposed for the Italian iron medal of honor (croce di ferro). Some sources claim the date of attack was actually in September 1941 (https://www.mentaerosmarino.it/wp-content//uploads/2017/10/Rosa-Costanza-Danielli.pdf).

HERITAGE

The main heritage is the construction of an extensive network with nearly six thousand kilometers of paved roads in all Ethiopia, as recognised by the same emperor Haile Selassie. The main road created by the Italians was the fully asphalted Addis Abeba-Asmara/Massaua, that broke the historical road "isolation" of the Ethiopian capital.

Additionally it is noteworthy to remember that actually (2023) there are only a few Italian-ethiopians descendants -may be nearly one thousand- of the 40000 colonists (who settled in the city in the fascist years). But there it is still a good Italian heritage from them in contemporary Addis Abeba (from constructions to food, etc..). There it is also an area in actual Addis Abeba called "Old Italian district" around the historical "piassa" (https://ethiopianbusinessreview.net/piassa/).

Photo of a typical ethiopian food: "injera" with italian spaghetti -heritage from the "Etiopia italiana" years- and now called "pasta saltata" in Addis Abeba (https://www.kqed.org/bayareabites/138982/how-colonialism-brought-a-new-evolution-of-pasta-to-east-africa).

In 2020 the small community of the Italians and Italo-ethiopians of Addis Abeba lived around this famous "piazza" (square) - called locally "piassa" (https://salamboinaddis.com/2012/12/19/the-italians-of-addis/) and located in the oldest area of the city.

INFRASTRUCTURES

Map showing the roads created by the Italians in 1937-1940 (in dark black the fully asphalted)

The Italians invested a lot in Ethiopian infrastructure development, mainly in the capital region. They created the "imperial road" between Addis Abeba and Asmara/Massaua, the Addis Abeba - Mogadishu and the Addis Abeba - Assab. Also, the Addis Abeba-Berbera/Hargeisa was nearly completed when WW2 blocked all the road constructions.

Indeed in the few years of Italian rule in Ethiopia were done two important improvements: the complete abolishment of slavery and the road construction of a communication system in a mountainous country.

Furthermore, 900 km of railways were reconstructed or initiated (like the railway between Addis Abeba and Assab), dams and hydroelectric plants were built and many public and private companies were established in the underdeveloped country.

The most important -with their headquarters in Addis Abeba- were: "Compagnie per il cotone d'Etiopia" (Cotton industry); "Cementerie d'Etiopia" (Cement industry); "Compagnia etiopica mineraria" (Minerals industry); "Imprese elettriche d'Etiopia" (Electricity industry); "Compagnia etiopica degli esplosivi" (Armament industry); "Trasporti automobilistici (Citao)" (Mechanic & Transport industry).

Actual photo of the Italian-era building of the Ethiopian Electricity company, built in the early 1940s in typical modern Italian style.

Italians even enlarged and created new airports (like the "Ivo Olivetti aeroporto", that actually is called "Lideta airport" in the outskirts of Addis Abeba) and in 1936 started the worldwide famous "Linea dell'Impero", a flight connecting Addis Abeba to Rome.

Addis Ababa was incorporated into the imperial italian network of fligths, being served four times a week with the Savoia Marchetti, SM-73 airplanes: in two days (and no more in a week) Italy was connected with Ethiopia, also with a new daily postal service.

ALA LITTORIA: "Orario estivo del 1938" (Timetable of the "Linea dell'Impero")

The line was opened after the Italian conquest of Ethiopia and was followed by the first air links with the Italian colonies in Africa Orientale Italiana (Italian East Africa), which began in a pioneering way since 1934. The route was enlarged to 6,379 km and initially joined Rome with Addis Ababa via Syracuse, Benghazi, Cairo, Wadi Halfa, Khartoum, Kassala, Asmara, Dire Dawa .

There was a change of aircraft in Benghazi (or sometimes in Tripoli). The route was carried out in two and a half days of daytime flight and the frequency was four flights per week in both directions. Later from Addis Ababa there were three flights a week that continued to Mogadishu, capital of Italian Somalia.

The most important railway line in the African colonies of the Kingdom of Italy as the Djibouti-Addis Ababa. It was long 784 km and was acquired following the conquest of the Ethiopian Empire by the Italians in 1936.

The route of the railway was protected by special Italian military units since 1936 and until 1938, when the Ethiopian guerrilla finished and all the regions crossed by the trains were fully "pacified".

The railway Addis Abeba-Djibouti was officially declared safe and "pacified" from summer 1938

The route was served until 1935 by steam trains that took about 36 hours to do the total trip between the capital of Ethiopia and the port of Djibouti. Following the Italian conquest was obtained in 1938 the increase of speed for the trains with the introduction of four railcars high capacity "type 038" derived from the model Fiat ALn56 (http://www.train-franco-ethiopien.com/photos_cfe/autorails_fiat_cfe/pages/image/imagepage15.html ). These diesel trains were able to reach 70 km/h and so the time travel was cut in half to just 18 hours: they were used until the mid 1960s (http://www.train-franco-ethiopien.com/photos_cfe/autorails_fiat_cfe/pages/image/imagepage30.html). At the main stations there were some bus connections to the other cities of Italian Ethiopia not served by the railway (http://www.train-franco-ethiopien.com/photos_cfe/gare_diredawa_cfe/pages/image/imagepage15.html).

Additionally, near the Addis Ababa station was created a special unit against fire, that was the only one in all Africa (Railways map -enlarge to world map!: [https://openrailwaymap.org/?style=standard&lat=45.37626702418105&lon=6.249847412109375&zoom=9 ]).

ARCHITECTURE

Cinemas & Theaters

The first Italian cinema in Addis Abeba was the "Romano", opened in October 1936 , followed by the "Marconi" in via Tripoli. The "Cinque Maggio" and the "Italia" cine-theater of the 'House of the Fascist Hospitality' were inaugurated both in 1937.

The "Italia" was a super cinema with 1200 seats. It was used also as a theater and for opera activities.

The "Impero" in via Massaia and the "Roma" were built later, just before WW2 started.

Late 1939 photo of the cinema "Impero"

In 1939, the new "Marconi" cinema-theater was designed by Ippolito Battaglia.

The cinema showed the same morphology of the elements used in the project of the building for the government offices (prepared in the same years by architect Plinio Marconi for the monumental area of the city).

Hospitals

In Addis Ababa, at the time of taking possession of the city, were recovered and restructured by the Italian government some of the existing health facilities: the Ospedale Italiano/Italian Hospital "Principessa di Piemonte" (built by the "Italica Gens" - A.N.M.I.), the Hospital "Duca degli Abruzzi" (only for Italians) and the Hospital "Vittorio Emanuele III" (only for indigenous Ethiopians).

The Italian hospital, showed a "classicism" shape with clad in light yellow trachyte stone and decorated by red brick; it was built from 1931 to 1934 on a project by engineer Piero Molli from Turin and it was among the first three-story buildings of the city, built with reinforced concrete frames. The engineer of the works was Mario Bayon, while the structural calculations were performed by the engineer Giberti. In October 1939, an additional expansion was studied.

INSTITUTIONS

Schools

*Scuola elementare mista Vittorio Emanuele III of Addis Abéba.

*Ginnasio-Liceo Vittorio Emanuele III

*Istituto tecnico Benito Mussolini

*Missione della consolata (asilo d infanzia e scuola elementare parificata mista).

*Scuola parificata mista del Littorio. Missione delle suore canossiane (scuola parificata, a Cabanà). Missione San Vincenzo da Paola (scuola governativa per tracomatosi).

*Missione della Consolata (scuola parificata, brefotrofio per bambine, orfanotrofio).

*Missione della Consolata (college for the sons of Ethiopian authorities, under the "Direzione superiore affari politici").

*School for muslims

Photo of Italian colonists in a 1939 folklorist meeting in the Addis Abeba outskirts, celebrating with Italian regional dances

Viceroy Amedeo D'Aosta planned to bring 20,000 Italian colonists in 1942 to live in the Scioa region, imitating what was done in Libya with the 20,000 colonists who successfully settled there in 1938. Mussolini by 1956 (in order to commemorate twenty years of the Italian empire existence) wanted to move half a million Italians to live in the Ethiopian Highlands, but WW2 blocked all these projects

Associations

* Sopraintendenza scolastica. *Casa del fascio. *Istituto di cultura fascista. Opera nazionale dopolavoro.

*Gioventù italiana del littorio.

*Fascist university group. The Gioventu Universitaria Fascista (GUF) of Addis Ababa, made up of volunteers from the Ethiopian war and directed by Fabio Roversi Monaco, played an important role in the promotion of cultural activities in the empire. The preparation of prelates and assistance to graduates for enrollment in Italian faculties were also fundamental. In 1939 the GUF asked the government to evaluate the possible creation of a university of the empire or, at least, to allow the exams to take place directly in Addis Abeba.

*Ufficio stampa e propaganda AOI.

*Casa dei giornalisti.

*Ufficio superiore cartografico.

*Museo dell impero.

*Opera nazionale combattenti.

*Regio automobile club d Italia.

*Consociazione turistica italiana; Compagnia italiana turismo cinema, teatri, radio.

* Istituto luce Impero Italiano

*Cinema teatro Italia (Casa dell ospitalità fascista)

*Cinema Impero

*Cinema Romano

*Cinema Cinque maggio (for native ethiopians)

* Stazione radiofonica Eiar (with auditorium) of the Istituto Luce (Ethiopia).

Newspapers and magazines

*«Corriere dell Impero» newspaper (called "Quotidiano di Addis Abeba" from March 1938 until February 1938 as journal of the "Federazione dei fasci di combattimento"; from May to December 1936 called «Il Giornale di Addis Abeba»)

*«Il Lunedì dell Impero» (magazine of the «Corriere dell Impero»)

*«Marciare» («Magazine of "Goliardia fascista dell Impero". Giornale mensile di avanguardia del Guf»)

*«Ye Chessar Menghist Melchtegnà» («Corriere dell Impero» in Ethiopian language). Weekly magazine published by the «Barid al-imbiraturiyyah»

*«Il messaggero dell Impero»; weekly newspaper in arab language published by the " Ufficio stampa e propaganda"; from March to December1938 «Kuriri di Imbiru»( inside the «Corriere dell Impero])

*«Ye Roma Berhan» («Luce di Roma»).Monthly magazine in Aramaic language.

*«Addis Abeba» (monthly magazine of the Addis Abeba city hall)

*«Etiopia Latina» (monthly magazine)

*«L Impero illustrato» (weekly magazine); «Notiziario mensile della MVSN nell AOI»; «L Impero del Lavoro» (magazine of the "Ispettorato fascista del lavoro")

*«Rassegna sanitaria dell AOI» (weekly magazine published by the "Società di medicina dell impero")

*«La Consolata in AOI» (monthly magazine of the "Missione della Consolata editori"

*Tipografia del Governo; Generale Stamperia del Littorio

*Tipografia della missione della Consolata

*Bulletins/Journals: Giornale ufficiale del governo Generale dell Africa Orientale Italiana e Bollettino ufficiale del Governo dello Scioa» (weekly); «Foglio d ordini e di comunicazioni del Governo Generale dell Africa Orientale Italiana» (monthly) ; «Foglio d ordini dello Stato Maggiore del Governo Generale dell Africa Orientale Italiana» (monthly) ; «Foglio d ordini e di comunicazioni del Governo dello Scioa» (monthly) ; «Bollettino dell Ufficio dell Economia Corporativa dello Scioa» (monthly); «Bollettino dell Economia Corporativa dello Scioa» (monthly) «Scioa» (monthly published by the "Ufficio della produzione e del lavoro"); «Bollettino di idrobiologia, caccia e pesca dell Africa Orientale Italiana» (news from the "Servizio di idrobiologia e pesca e della Sovrintendenza alla caccia"

LINKS

* PHOTOS of Italian Addis Abeba: http://senato.archivioluce.it/senato-luce/ricerca/libera/esito.html?query=addis+abeba Photos of Italian Addis Abeba

* VIDEOS of "ISTITUTO LUCE" related to Addis Abeba:https://patrimonio.archivioluce.com/luce-web/search

/result.html?luoghi=%22Addis%20Abeba%22&activeFilter=luoghi

The following is an essay about Addis Abeba (the capital of Ethiopia) when was under Italian rule from 1936 until 1941. The essay was written by Bruno D'Ambrosio of the University of Genova (Universita' Statale di Genova - Italia):

ADDIS ABEBA ITALIANA

Map of Italian Plan for Addis Abeba marketplace site: (1) Italian City; (2) Natives' City. Original in "Gli Annali Dell'Africa Italiana". Anno II -Numero 4 -1939 -XVIII

On 5 May 1936, Italian troops occupied Addis Ababa (usually called Addis Abeba) during the Second Italo-Abyssinian War, making it the capital of "Italian East Africa". Addis Ababa was governed by the Italian Governors of Addis Abeba from 1936 to 1941 (https://www.worldstatesmen.org/Ethiopia.html#Italian-East-Africa). In those five years the Italian government made many improvements to the city, from the construction of Hospitals and roads to the creation of stadiums like the Addis Abeba stadium (www.artefascista.it/adis_abeba__fascismo__architettur.htm).

Indeed in less than three years (1938/1940) -after the arrival of the Viceroy Amedeo D'Aosta and the first successes against the Ethiopian guerrilla (called "arbegnocs") with the complete "pacification" of the region (called "Scioa" and sometimes "Shewa") around Addis Abeba- there was in the city & surroundings:

1) a rapid increase in public works, 2 the construction of an extensive road network with six thousand kilometers of paved roads, 3) a visible improvement of agriculture and veterinary services, 4) the construction of clinics and (previously non-existent) health care places located every thirty kilometers, 5) an appreciable spread of education and various forms of assistance and 6) a generalized development of Italian entrepreneurship and work.

The first radio broadcasts in Addis Abeba & Ethiopia were created in 1937, when many radio-programs were done in Italian language for the Italian colonists

The Ansaldo Corporation of Italy in 1935 created a one-kilowatt station in the outskirts of Addis Abeba, inaugurated with a speech of emperor Selassie. The Italians took over the station in early 1936 and planned to develop it into a communications center for their new empire, joining those already established in Somalia and in Asmara (Radio Marina). A more powerful radio station of seven kilowatts was started by the Italians in 1937 (broadcasting the first radio-programs of Ethiopia, as can be seen in the above photo).

The Bank of Italy issued the loan "City of Addis Ababa" for 200 million lire, and in the spring of 1940 the city appeared to be a huge construction site with big investments done by the italian government. When Italy entered the war in 1940, the attack on British Somalia in the summer of 1940 and the British counter-offensive in early 1941 blocked all the works of Addis Ababa.

The news of the construction of the new capital disappeared from the Italian press after the end of WW2, as nearly all the traces of the Italian occupation were later canceled from the current city.

Aerial view of the Addis Abeba center in the urban masterplan of 1939 Italian Ethiopia

Mussolini promoted the development of Addis Abeba: he spent 53 billion current lire for the war and civilian building projects in Ethiopia. This remarkable sum (no other colonial power had spent so much money on the colonies, and in such a short time) reached over 10 % of Italy's GNP in 1936, the year of greatest expenditure.

Total State expenditure for civilian works in Italian East Africa between 1937 and 1941 amounted to about 10 billion current lire, of which over 8 were spent on roads and about 2 for other building works. The road building plan, directly conceived by Mussolini, met with several of the regime’s aims: a political aim, because the new roads would represent, vis-à-vis the rest of the world, the unmistakable sign of fascism’s new imperial civilisation; a military aim, because roads would open up the whole of the Ethiopian territory to the Italian army; moreover, road-building would also have great social relevance, by facilitating the migration and settlement of Italian colonists; finally, roads would also be economically important, because they would help develop a wider market for both Italian and local wares, and would involve thousands of building and transport firms in the actual construction works, as well as about 200 000 Italian and 100 000 African workers.G. Podesta'

It is noteworthy to pinpoint that in 1940 there was a satisfactory management -by the Italian government- of relations with different religious cults and that in Addis Abeba (and Ethiopia) there was the construction of churches and mosques without problems.

The Italians favored the development of catholicism in Addis Abeba, also between the ethiopian natives. They enlarged and improved the Cathedral of Addis Abeba.

BRIEF HISTORYbr/>

Map showing the Italian conquest of Addis Abeba and Ethiopia in 1935-1936

The city of Addis Abeba was conquered by Italian troops in 1936 and soon was declared the capital of the new Italian empire.

Addis Abeba grew from 45,000 inhabitants in spring 1936 (when the Italians won the Italo-Ethiopian war) to nearly 150,000 in spring 1941, when the Italians were defeated and the Allies (with emperor Selassie) returned to the city.

The city, that looked in 1935 like a medieval town (also because of thousands of slaves living in dire conditions) in just five years was transformed in a modern capital where more than 40,000 Italians lived in a city with a typical XX century society, free of slavery and full of developments & improvements.

Indeed during Italian rule, the Italians abolished slavery in all Ethiopia, issuing two laws in October 1935 and in April 1936 by which they declared to have freed 420,000 people. After Italian defeat in Second World War, Emperor Haile Selassie, who returned to power, abandoned his previous ideas about a slow and gradual abolition of slavery in favor of one that mirrored Italy’s civilized abrogation (abolition-of-slavery-in-ethiopia)

Italian propaganda postcard showing the freedom from slavery of Ethiopians by the Italian troops of the "Divisione Sabauda" in 1935

So, the first thing the Italians did in the just conquered city was to proclaim the end of slavery and to make free nearly 10,000 slaves in the Scioa region.

The british Lady Kathleen Simon of the "Anti-Slavery Protection Society" was one of the first to appreciate this action and the definitive end of slavery in Ethiopia.

Indeed in Addis Ababa the situation was full of expectatives after the Mussolini proclamation of the "Italian Empire" in May 9, 1936. The capital of the empire was due to become, in Mussolini’s opinion, the most beautiful and futuristic city in Africa, the beacon of the new fascist civilization. The preparation of the new town planning scheme was very long and problematic, involving top professional people like Giò Ponti, Enrico Del Debbio, Giuseppe Vaccaro and even Le Corbusier, who personally asked Mussolini to be allowed to design the plan for the new city (Le-corbusiers-visions-for-fascist-addis-ababa/).

However the city in May 1936 had no major infrastructures: there was no electricity in many areas, there were no sewers at all, only a few roads were asphalted and the city lacked a road network connecting with other Ethiopian urban centers. But there was an aqueduct in operation, which supplied only some areas, while fast transport was provided only by the Gibuti-Addis Ababa railway line, built by the French and inaugurated in 1917. The Italians solved all these infrastructure problems in a few years of hard work!

The famous "Villa Italia" in the outskirts of the city was improved in late 1936, as a residence of the main Italian authorities ( https://baldi.diplomacy.edu/diplo/texts/Del_Papa_VillaItalia.pdf).

In autumn 1937, the result of the initial works managed by the Governorate of Addis Ababa in a year and a half of activity was, all in all, positive: the repaving of the main roads, the restoration of existing health facilities, the expansion of some hotels and the restructuring of the natives market. Moreover six buildings of the I.N.C.I.S ( housing institution for government employees) were built. And also the "Casa del Fascio", both inaugurated on 28 October; while the Regulatory Plan Office had expropriated property in the industrial zone and some areas had been given in concession to institutions and private individuals.

Video of initial Italian constructions in 1936 Addis Abeba:

However work started on a full scale only in 1939. The fourth and last definitive Addis Abeba urban plan -approved by Mussolini- provided for a clear separation between the European and indigenous areas. This would have meant transferring the African population and building tens of thousands of new homes.

Indeed the definitive Urban Plan for Addis Abeba was approved by Mussolini in late 1938 (with the "green" separation of the native southern quarters from the Italian northern quarters), but was never fully created, because of WW2.

After the conquest of the city, some Ethiopians started a guerrilla war with terrorism in all Ethiopia and many italian and eritrean soldiers were attacked and sometimes murdered even in Addis Abeba. In February 1937 -after nearly 200 Italians and Eritreans (including women) have been attacked & murdered by the "arbergnocs" in the city's area- happened the attempted assassination of Marshal Rodolfo Graziani, Marquis of Negele, Viceroy of Italian East Africa. As a consequence the Italians did a massacre of suspected Ethiopians and since then the city was fully "pacified" until the british conquest in 1941.

Because of the complete lack of terrorism in Addis Abeba, many Italian colonists settled in the city after 1937 and the city flourished in an astonishing way: Italian settlers had increased from a few thousands in early 1937 (with 150 families) to over 40,000 in March 1940 (33,059 men, 6,998 women and about 4,000 families) whilst the African population had practically doubled and was estimated at about 100,000 people.

When started WW2 Addis Abeba was a capital with nearly 150000 inhabitants and looked more like a busy european city with a booming development than a lazy african colonial city.

Furthermore ut is noteworthy to pinpoint that the "Health Corps" of Italian Africa was created only in 1936, and it was made up of about 200 doctors and health inspectors, by organising a special public competition which took place between 1937 and 1938. Three centres were gradually built in Addis Ababa, Asmara and Mogadishu, specialised in the cure of malaria, as well as numerous hospitals and clinics. Following direct orders by Mussolini, since 1936 special attention was naturally given to the prevention and cure of venereal diseases (since the authorities could not prevent contact between Italian men and African women), by rounding up and imposing forced hospitalisation on thousand of native women in special “syphilis homes”.

As a consequence towards the end of 1938 the incidence of sexual diseases had dropped: the percentage of Italian soldiers suffering from venereal diseases was about 5 % compared to 10 % in 1937, whilst that of civilians, which was much lower, had decreased from 1.4 to 0.9 %. An improvement was also registered among indigenous military personnel, from 3.7 % to 2 %. These data of course reinforced Mussolini’s will to increase the number of whole families emigrating from Italy to AOI. A remarkable effort was made to improve healthcare: beside the doctors belonging to the Italian Africa Health Corps, flanked by 450 military doctors, there were about 500 civilian doctors (232 specialists, among whom 30 paediatricians, and 262 general practicioners). Special maternity wards were built in the hospitals situated in the main locations.

The new Italian hospital in Addis Ababa had a delivery room and a pediatric clinic for Italians, with a capacity of over 100 beds in its various sections: expectant mothers, postpartum mothers, babies’ room, gynaecological ward, infectious diseases, visitors’ room, etc. The children’s hospital was subdivided into separate wards for babies and older children, for infectious, gastro-intestinal or pulmonary diseases, etc. Moreover, a university-type faculty was founded in early 1940 in Asmara to train nurses and the same was planned for Addis Abeba.

In Addis Ababa the number of new-born Italian babies was continually growing, rising from 50 in 1937 to 570 in 1939 and the number of weddings being celebrated shot up too, despite the dramatic housing shortage. Italians lived in all possible ways: many continued to live in temporary shelters (tents, huts and prefabricated houses), whilst a lot of families used indigenous homes that had been expropriated or rented.

Mussolini found this situation intolerable, and he constantly urged the Italian East Africa’s government to ensure a more vigorous policy of racial separation (on his orders the African market had been forbidden to Europeans, but the measure was later withdrawn, because indigenous trade was indispensable for the provision of food by whites).

As Amedeo d’Aosta (the new Viceroy of AOI since 1938) once remarked, the solution of the problem of racial prestige was incompatible with the housing situation: firstly, there was not enough money to build houses for Italians or tukuls in the new indigenous town, then there were huge difficulties in sourcing water and building materials; that is why most Ethiopians, after cashing in their expropriation indemnity, went back to the old quarters.

The 1938 arrival to Addis Abeba of Viceroy Amedeo D'Aosta

To confront the situation, given that, as the Viceroy Amedeo repeated, it was impossible to separate the two races “by evicting one hundred thousand natives”, and whilst waiting for the implementation of a low-cost building programme for the colonists, it was necessary to stop new family units emigrating to Italian East Africa.

To house the families of AOI government employees, who had been forced by Mussolini to take their wives and children to Africa, the national housing body for civil servants (INCIS - "Istituto Nazionale Case degli Impiegati dello Stato") financed the construction of 42 buildings with 119 flats, largely insufficient to satisfy all requests. Private individuals did not have any incentives to invest in residential building save for exceptional cases. Notwithstanding the “winds of war”, only in July 1939 a law was emanated which authorised banks operating in AOI to grant loans and mortgages to institutions, societies or private citizens who wished to build civilian houses (including cheap homes), and the planning schemes of the most important towns were completed only on the eve of WWII.

The war definitely put an end to all works in progress, and today there are just a few traces of the five years of Italian occupation .

But if the new imperial cities had trouble in taking shape, social life in Addis Ababa and Asmara was pulsating just like that of any other European town. At the heart of the city were the markets: in the Ethiopia capital in 1939 over 75,000 heads of cattle had been slaughtered and thousands of tons of foodstuffs had been sold. Dozens of shops and even department stores were opened in the Scioa cities. Leisure activities also boomed: in Addis Ababa four cinemas had been built for Europeans and one for Africans.

New dancehalls, restaurants and bars were being opened everywhere. The working men’s clubs and numerous sports and recreational societies, supported by local government and by the PNF, organised the colonists’ free time. In the Scioa governorate, near the strategic hubs where companies and the army had located their logistic bases, new urban agglomerates rose from scratch, with plenty of restaurants and clubs.

The Italians were the first to promote the football in Ethiopia, after 1937. No overall Ethiopian championship was played in 1938 and 1939, but there were regional leagues in the provinces of Amhara (capital Gondar), Harar (capital Harar), Scioa (capital Addis Abeba) and Galla e Sidama (capital Jimma).

In the Scioa governorate the team participants were made of amateur Italian players -playing mostly in the newly created "Campo Sportivo "Littorio" (video of Littorio's inauguration: http://senato.archivioluce.it/senato-luce/scheda/video/IL5000027374/2/Impero-Italiano-Addis-Abeba.html ), the first football stadium of Addis Abeba. Successively it was enlarged in 1940 (with tribune and athletic lanes). These teams included: Ala Littoria; A.S.A. Citao; Littorio; M.V.S.N.; S.S.Pastrengo ; Piave ; A.S. Roma d'Etiopia-Addis Abeba. However the war stopped these amateur Championships in 1940.

In 1944 the first Ethiopian Championship was held in Addis Abeba, with 5 teams representing the various communities in the capital conquered by the Allies. In the final match the BMME of the British Army won the Fortitudo of the remaining Italian colonists. Participants: St. George (Ethiopian); BMME (British); Fortitudo (Italian); Ararat (Armenian); Olympiakos (Greek).

Italian soldiers paving-asphalting roads in 1937 Addis Abeba center

The Italian Fascist Party (PNF) was a crucial instrument in moulding colonial society in a fascist sense and also in the involvement and training of those Africans destined to fill some inferior role in the civil administration or in the army, through school education and the Gioventù Indigena del Littorio (GIL – the fascist indigenous youth organisation).

Italian colonists’ degree of adhesion to the fascist party was massive, well above the percentage of party members back in Italy, especially among women: at the end of 1939 the PNF had 51,146 members in the colonies, whilst pending applications for membership amounted to 24,397 and those transferred from Italy were 9,950: nearly one third were in Ethiopia (mainly in the capital area). There were 3,308 women enrolled in the fascist organisations (12.8 % of the female population). There also were 237 fascist working men’s clubs with 38,235 members and 106 sports societies with 19,822 members.

Colonisation represented a major turning point in the life of thousands of settlers. The regime conceived a new social plan for the empire, consisting of a society made up by brave and hard-working Italian colonists.

1938 map of the Scioa governorate around Addis Abeba, South of the capital can be seen the "Azienda Agricola Biscioftu" (a huge farm development, with Italian colonists)

Furthermore, since 1937 the peripheral lands around Addis Abeba were improved with colonization projects: the full "pacification" of the Ethiopian guerrilla in the Scioa region allowed in 1938 to start farm projects with Italian colonists.

So, in the same year the O.N.C. ("Opera Nazionale Combattenti") created two modern farms in Olettà, a center about 40 kilometers from Addis Ababa and in Biscioftù, at the same distance from the capital but on the route to Djibouti.

For the valorization of the country around Addis Abeba, other development models were taken into consideration, such as the "capitalist-type colonization" guided by the large private capital (for example, in Addis Alem a factory for the production of slaked lime was established under the Italian management, and in its first year of production it turned out 30,000 hundredweights of the material).

It was considered also the so called "industrial-type colonization", in which the concessionary companies would manage the transformation of agricultural and mining products. Belonging to the latter type was the "Villaggio Torino", designed by Giorgio Rigotti and built about 35 kilometers from Addis Ababa. This was an industrial plant linked to agriculture with a high-rise mill, a pasta factory and a biscuit factory, annexed to which there was a small Italian workers' settlement and an indigenous neighborhood

In 1940 an Italian government study found that there were nearly half a million native Ethiopians (mainly living in the Scioa governorate, where the capital was Addis Abeba) who were receiving salaries from the Italians (in the Army, in the civilian administration, in many private companies and also inside Italian families as maids/nurses/housekeepers): the living standards of the autochthonous Etiopians in these areas increased to levels never historically reached before (G. Podesta, "Emigrazione in Africa Orientale" emigrazione italiana nelle colonie africane ).

After their conquest of Ethiopia, the Italians acted quickly to reorganize the educational system in Ethiopia, that was in a very low level of development (in a country of nearly 6 millions there were only 8,000 students enrolled in twenty public schools in 1935).

A remarkable effort was made to establish a school system in AOI, both for Italians and for Africans. Schools for Italian students were built in thirty locations. Some secondary schools of all kinds were also created in Addis Abeba and in the main Ethiopian towns.

The two most important Italian schools in Addis Abeba were the Liceo-Ginnasio Vittorio Emanuele III and the Istituto Tecnico Benito Mussolini, both reserved for Italian children, while the prewar Empress Menen School for girls was converted into the Regina Elena military hospital. In the city some elementary schools were established for the Italians ( educazione italiana nelle colonie africane ), while also a few new schools were created for the native population: the Italian government pinpointed in 1939 that there were thirteen primary schools in the Scioa governorate, staffed by over sixty teachers and having an enrollment of 1481 Italians & native Ethiopians.

Additionally it is noteworthy to pinpoint that the 512 young Italians enrolled in the "Gioventu Universitaria Fascista" (GUF) in Addis Abeba requested the creation of a university institution in the capital of Ethiopia. In 1939 the GUF asked the government to study this possibility (or at least to allow exams to be done directly in Addis Abeba), but the start of WW2 stopped all this process and the first university in Ethiopia was created only in the 1950s by the French Jesuit Lucien Matte.