The following is a translation in english of some excerpts of a research done by Michele Pigliucci, about the nearly complete disappearance of the italian community in the "Venezia Giulia" and "Dalmazia" regions of Italy during the ten years after the end of World War 2. This disappearance has been defined by some historians (like Sabbatucci) with the word "ethnocide" (mainly in Dalmatia, where the italians of Dalmatia are now reduced to only a few dozens!).

The Italians of "Piemonte d'Istria" exiled in 1954 in Trieste. Photo done in 1959

"La diaspora dei giuliani e dei dalmati: una ferita ancora da sanare" (The diaspora of Julians and Dalmatians: a wound still to be healed), by Michele Pigliucci

The Julian-Dalmatian exodus refers to the mass migratory phenomenon that occurred between 1944 and 1954 which involved a substantial percentage of the inhabitants of the Italian region Venezia Giulia, a geographical region enclosed between the Julian Alps, the Isonzo river and the sea, and including the Gorizia karst , the Trieste karst and the Istrian peninsula up to the Gulf of Quarnaro.

The phenomenon largely occurred after the cessation of hostilities during the Second World War, at the end of which almost all of the Venezia Giulia region had passed under the sovereignty of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia; it was a phenomenon that involved the majority of the Italian population of the region, who decided to abandon their homes to flee to Italy, often in a daring way, taking with them what was possible to close in a chest or pile up on a cart and often even the coffins containing the remains of their own deads.

The figures referring to the extent of the phenomenon have often been manipulated for political interests, oscillating between the three hundred and fifty thousand mentioned by Father Flaminio Rocchi and the two hundred thousand reported by the Slovenian scholar Zerjavic.

But the most reliable figure is that of the "Opera Profughi" (Opera Refugees), who took a census of 201,440 people to which the historian Raoul Pupo believes it is necessary to add the number of those who for various reasons escaped the count, thus arriving at a reliable total of just over three hundred thousand people.

This is almost all of the Italian population in the area, an exodus of dimensions indeed impressive, unprecedented in the history of Italy.

When Italy signed the armistice in september 1943, the Yugoslav partisans of the Popular Committee for the Liberation of Istria proclaimed from

Pisino (actual Pazin in central Istria), with a nationalistic language, the return of Istria to the Croatian motherland, and occupied the whole region left without any political and military authority; established people's courts with which they began a ferocious liquidation of Italians (but also of some fascist Slovenians and Croatians) accused of being enemies of the people.

Several hundred people disappeared in those few months when drowned in the sea or shot on the edge of a foiba, often thrown alive and after being tortured; the victims were both military and civilians with positions during the regime, but also people completely unrelated to fascism such as Norma Cossetto, a university student who was arrested and raped by several men before being thrown alive into a foiba.

The region (after a few weeks of partizan occupation) remained under German administration up to spring of 1945, when the last Allied advance got the better of the exhausted Nazi-fascist troops: the 4th Yugoslav Army also took part in the offensive -which was ordered by Marshal Tito- to give the absolute precedence to the full occupation of Trieste. The city was reached on May 1 even earlier than Lubliana, just one day earlier than upon the arrival of New Zealand soldiers. It was the so-called «race for Trieste», which Tito knew was strategic for the purposes of the future structure

geopolitics of the area.

With the withdrawal of the German troops and the definitive disbandment of the departments of the Italian Social Republic, all of Venezia Giulia was also occupied by the Yugoslavs who resumed arrests, summary trials and eliminations of those who for various reasons were denounced as enemies of the people by the many informants in the area. After forty-two days of occupation the Yugoslavs left Trieste, Gorizia and Pola while the rest of the istrian territory became de jure Yugoslav territory (with the exception of the north-western coastal area up to the Mirna river which will constitute the "Free Territory of Trieste" until 1954).

It was then when began the "exodus" of the Italian population, whose origin can be traced back to three reasons: one linked to security, one political and one national.

The flight of the Italians was above all a reaction to the liquidations and the violence implemented by the Yugoslav regime and in particular by the secret police, the OZNA. The large number of people disappeared and killed in sinkholes (called "foibe" in italian) throughout the territory greatly frightened the Italian population, so much so that historian Sabbatucci does not hesitate to speak of "ethnic cleansing" towards the Italians, convinced that there was precisely behind these liquidations the will of modify the ethnic structure of the territory by eliminating the Italians especially before the Peace Conference defined sovereignty over the area.

The political motivation, consisting in the desire not to submit to a communist regime, then played a fundamental role both in the Italians of the exodus and in the "remained" italian community (confident in the nascent regime) and both for the Italian workers who decided to cross the border in the opposite direction in order to do adherence to the ideal of socialism. Many of those workers, however, will be persecuted as "cominformists" after the break between Tito and Stalin.

Finally, it affected the choice to flee also the national identity, on which the exile memoir insists a lot, which often tells of a voluntary exile, motivated by the desire to continue living in an Italian land. The strong national sense of these populations, on which they had Irredentism and Fascism, and the millenary rivalry with the Slavs, found fertile ground and certainly contributed to this choice. In the first post-war years, together wjth the violence, the regime titino undertook a work of Slavicisation of the region similar to that of Italianization conceived by fascism: the Italian shop signs, the use of the Italian language was substantially prohibited, many Italian schools were closed and it was banned enrollment in the same to all children whose surname ended in «-ch», automatically considered Italianized Slavs.

The five exodus waves

The exodus materialized in five main waves corresponding to as many historical events:

1) A first wave followed the fierce Anglo-American bombing of Zara, whose inhabitants had already sought refuge in Italy in 1944: the abandoned city would later be occupied by Tito's partisans and the Italians would never return.

2) The second wave followed the definitive annexation of the vast majority of the Istrian region, Fiume and the Dalmatian lands in June 1945.

3) A third wave took place in the winter of 1947, when also Pola passed under Yugoslav control following the signing of the Peace Treaty: in the city there were tens of thousands of inhabitants (nearly all the "Polani") who decided to embark to reach Italy.

4) In 1948 a new wave affected the communists who had wanted to stay or who had moved to Tito Yugoslavia and who, after the Tito's expulsion from the Cominform in 1948, had ended up as enemies of the yugoslav regime because loyals to the Partito Comunista Italiano.

5) The last big wave finally occurred in October 1954, no less than nine years after the end of the war, when the London Memorandum established the passage of Trieste to Italy but handed over to Yugoslavia the coastal area from Capodistria (now called Koper) up to the river Quieto (now called Mirna).

.

The arrival of the exiles on the national territory in 1945 and 1946 was the cause of harsh political disputes: the docks of the ports of Venice and Ancona they hosted, upon the arrival of the steamers, protest demonstrations from the side of dock workers who accused the Giuliani of fascism as fugitives from a communist regime. Disembarked on land, the exiles were then sorted onto the various trains that would take them to the 120 refugee camps scattered throughout Italy to host them as best they could: during the passage of one of these trains to the Bologna station, the workers even threatened to strike if the authorities had allowed the convoy to stop to receive the comfort of the Red Cross.

The Communist Party helped to spread hostility towards the exiles even in the final destinations of the journey, favoring the identification of the Giulians with war criminals forced to flee from Venezia Giulia to escape the reaction of their victims. This distrust spread significantly in Italy, also fueled by the precarious living conditions in which the exiles found themselves in the refugee camps.

In accordance with this attitude of mistrust the historiography official has ignored for decades the extent and sometimes the very existence of this tragedy. Still in the 90s of the twentieth century the manuals only marginally reported this page of history, which survived relegated to neo-fascist political propaganda and the memoirs of exiles. The bad reception given to refugees on the docks of the ports and in the stations was the prodrome of a more general removal not only of the story of the exodus, but also of much of the history of the Italian presence in Venezia Giulia and Dalmatia.

But among the causes that had led to the collective removal of this story of Italy it is impossible to deny how contributed the "shame" (promoted mainly by the Italian communists) due to the presence of the Italian element in Venezia Giulia & Dalmatia, considered alien and of colonial origin by the Yugoslavia of Tito. This belief results completely unfounded as the Latin element in Istria and in Dalmatia is autochthonous, historically documented without solution continuity from the Roman imperial age up to national Italian unification (called "Risorgimento") to which provided an important blood contribution.

Historical evidence does not permit misunderstandings: Italy, defeated in the Second World War, had to give away as a "repair" an entire region of its metropolitan territory (Venetia Giulia, Istria and areas of coastal Dalmatia), as large as Tuscany, whose population for the most part chose the path of exile both to escape the terror of the new communist regime Yugoslavian and to preserve its national identity.

Thursday, December 1, 2022

Wednesday, November 2, 2022

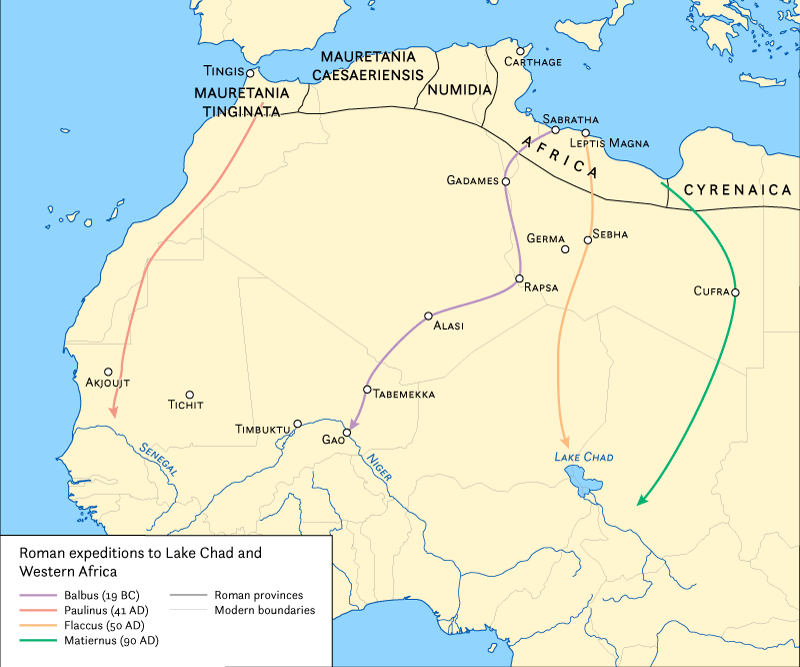

ROMANS IN EQUATORIAL COAST OF WEST AFRICA

Romans in the Gulf of Guinea

We know that Romans went to the north areas of subsaharan Africa from the Mediterranean coast of northern Africa, but some academics think that they probably reached also the Gulf of Guinea by sea and/or by crossing the Sahara. I am going to research this possibility.

HISTORY

When Romans conquered Carthage in the second century BC, they also obtained their huge commerce in the Atlantic coast of west Africa.

Indeed a sea-borne merchant people like the parent Phoenicians, the Carthaginians ranged far beyond the Straits of Gibraltar to trade with the Britons and with the Berbers of western Morocco. Sometime before 400 BC Hanno, a Carthaginian admiral, embarked with a fleet of sixty vessels on a famous voyage of exploration down the Atlantic coast of Africa.

He certainly reached the Gulf of Guinea and, from his report of gorillas, probably he arrived to the shores of modern Gabon, but he did not circumnavigate the continent as some have claimed. Furthermore the discovery, two centuries ago, of a cache of Carthaginian coins of the fourth century BC in the Azores—a third of the way across the Atlantic from Portugal—raises the question whether some stray Punic navigator may not even have discovered the New World.

It is noteworthy to pinpoint that the earliest recorded contact with the island of Mogador (near the coast of actual Western Sahara in southern Morocco) was by the Carthaginian navigator Hanno, who visited and established a trading post in the area in the fifth century BC. In the first century BC roman merchants settled in the island and established a small fortified settlement, which may have been the starting point for Roman merchants sailing to the Cape Verde islands and the Gulf of Guinea.

However Romans later conquered Carthago and maintained all trade done across the Sahara after the second century BC and until the fifth century AD. Indeed one roman named Iulius Maternus travelled the most south from the Mediterranean shores inside central Africa.

According to Marinus of Tyre (Ptol. 1,8,5), the roman Iulius Maternus together with the king of the Garamantes set off from Garama (near the Tibesti mountains in the south of actual Libya) to the south and, after four months and 14 days (Ptol. 1,11,5), reached the Ethiopian land of Agysimba, where they saw a great number of rhinoceros (cf. also Ptol. 1,7,2; 8,2; 6 f.; 9,8; 10,1; 11,4; 12,2; 4,8,5; 7,5,2). Maternus seems to have travelled as a trader between AD 83 and 92 AD. To our knowledge, he penetrated further than any other Roman into the African interior and probably reached the gulf of Guinea.

The landscape Agisymba embraced a vast area south of the Sahara from Lake Chad to the west to the Niger bend (and perhaps the delta) and belonged politically to the reign of the king of the Garamantes.This king had his headquarters in the city of Garama in today's Fezzan (western Libya). Agisymba is first time mentioned in the geographical work of the Alexandrian scholar Claudius Ptolemy (2nd century A. D.). An accurate localization of the landscape of Agisymba is still expected, but it is also believed in modern research to be an antecedent kingdom of Kanem. In the second half of the 1st century A D, Iulius Maternus who was probably a native of Roman North Africa, traveled from Leptis Magna to Garama.

There he joined the entourage of the king of the Garamantes and traveled further four months a southerly direction until the landscape Agisymba. There are various considerations, what role Iulius Maternus had played during this expedition: he was seen as a Roman general, as a businessman or as a diplomat. Raffael Joorde -a german historian- wrote that Maternus was a diplomat who received the unique opportunity to make the extensive territory south of the Sahara accessible for the geographers in the Roman world probably reaching the Atlantic ocean in actual Nigeria. The cause of this long journey is assumed by many researchers to be a military campaign of the king of the Garamantes against rebellious subjects.

However some historians (like Susan Raven) believe that there was even another Roman expedition to sub-saharan central Africa: the one of Valerius Festus, that could have reached the equatorial Africa thanks to the Niger river.

Indeed Pliny wrote that in 70 AD a legatus of the Legio III Augusta named Festus repeated the Balbus expedition toward the Niger river. He went to the eastern Hoggar Mountains and the entered the Air Mountains as far as the Gadoufaoua plain. Gadoufaoua (Touareg for “the place where camels fear to go”) is a site in the Tenere desert of Niger known for its extensive fossil graveyard, where remains of Sarcosuchus imperator, popularly known as SuperCroc, have been found). Festus finally arrived in the area in which Timbuktu is now located.

Some academics, such as Fage, think that he only reached the Ghat region in southern Libya, near the border with southern Algeria and Niger. However, it is possible that a few of his legionaries reached as far as the Niger river and went down to the equatorial forests navigating the river to the delta estuary in what is now southern Nigeria. Something similar may have occurred in the exploration of the Nile done under Emperor Nero in Uganda.

After the third/fourth century the roman contacts with sub-saharan Africa started to disappear, because of the final crisis in the roman empire

Maritime travels

Even maritime contacts happened in the western coast of Africa: there are some academic discussions about the possibility of further Roman travels toward Guinea and Nigeria and even the equatorial areas of the Gulf of Guinea.

XIX century map showing the Fernando Po island in the Gulf of Guinea. This island was known to the Romans as one of the "Hesperides": they knew that it was located at 40 days of navigation from the Cape Verde islands (called in roman times "Gorgades")

Indeed according to Pliny the Elder and his citation by Gaius Julius Solinus, the sea voyaging time crossing from the Gorgades (Cape Verde islands) to the islands of the Ladies of the West ("Hesperides") now known as São Tomé and Príncipe and Fernando Po was around 40 days (meaning that Romans knew the exact time needed to reach these equatorial islands -located in front of Camerun/Niger delta- and only with their direct exploration/navigation they could have know this precise time).

Furthermore, a Roman coin -in a good condition- of the emperor Trajan has been found in Congo (http://www.strangehistory.net/2015/02/10/roman-coin-congo/).

Roman coins have been also found in Nigeria and Niger; and in Guinea, Togo and Ghana too. However, it is much more likely that all these coins were introduced at a much later date than that when there was direct Roman intercourse so far down the western coast. But it is possible -even if with a possibility of a very minimal percentage of only 5%, according to researchers- that Roman merchants left there those coins doing their trade when reached the gulf of Guinea.

Finally it is important to remember that Augustus, based on the discovery of a sunken roman merchant ship from southern Hispania in the Djibouti area (in the horn of eastern Africa), wanted to organize around Africa a roman maritime expedition (to be done initially by his adoptive son Gaius Caesar when he sailed from Egypt's Berenice toward Aden).

It was going to be done -around 2 AD- from southern Egypt to Mogador and Sala (in actual Morocco). But it seems that it never took place.

We know that Romans went to the north areas of subsaharan Africa from the Mediterranean coast of northern Africa, but some academics think that they probably reached also the Gulf of Guinea by sea and/or by crossing the Sahara. I am going to research this possibility.

HISTORY

When Romans conquered Carthage in the second century BC, they also obtained their huge commerce in the Atlantic coast of west Africa.

Indeed a sea-borne merchant people like the parent Phoenicians, the Carthaginians ranged far beyond the Straits of Gibraltar to trade with the Britons and with the Berbers of western Morocco. Sometime before 400 BC Hanno, a Carthaginian admiral, embarked with a fleet of sixty vessels on a famous voyage of exploration down the Atlantic coast of Africa.

He certainly reached the Gulf of Guinea and, from his report of gorillas, probably he arrived to the shores of modern Gabon, but he did not circumnavigate the continent as some have claimed. Furthermore the discovery, two centuries ago, of a cache of Carthaginian coins of the fourth century BC in the Azores—a third of the way across the Atlantic from Portugal—raises the question whether some stray Punic navigator may not even have discovered the New World.

It is noteworthy to pinpoint that the earliest recorded contact with the island of Mogador (near the coast of actual Western Sahara in southern Morocco) was by the Carthaginian navigator Hanno, who visited and established a trading post in the area in the fifth century BC. In the first century BC roman merchants settled in the island and established a small fortified settlement, which may have been the starting point for Roman merchants sailing to the Cape Verde islands and the Gulf of Guinea.

However Romans later conquered Carthago and maintained all trade done across the Sahara after the second century BC and until the fifth century AD. Indeed one roman named Iulius Maternus travelled the most south from the Mediterranean shores inside central Africa.

According to Marinus of Tyre (Ptol. 1,8,5), the roman Iulius Maternus together with the king of the Garamantes set off from Garama (near the Tibesti mountains in the south of actual Libya) to the south and, after four months and 14 days (Ptol. 1,11,5), reached the Ethiopian land of Agysimba, where they saw a great number of rhinoceros (cf. also Ptol. 1,7,2; 8,2; 6 f.; 9,8; 10,1; 11,4; 12,2; 4,8,5; 7,5,2). Maternus seems to have travelled as a trader between AD 83 and 92 AD. To our knowledge, he penetrated further than any other Roman into the African interior and probably reached the gulf of Guinea.

The landscape Agisymba embraced a vast area south of the Sahara from Lake Chad to the west to the Niger bend (and perhaps the delta) and belonged politically to the reign of the king of the Garamantes.This king had his headquarters in the city of Garama in today's Fezzan (western Libya). Agisymba is first time mentioned in the geographical work of the Alexandrian scholar Claudius Ptolemy (2nd century A. D.). An accurate localization of the landscape of Agisymba is still expected, but it is also believed in modern research to be an antecedent kingdom of Kanem. In the second half of the 1st century A D, Iulius Maternus who was probably a native of Roman North Africa, traveled from Leptis Magna to Garama.

There he joined the entourage of the king of the Garamantes and traveled further four months a southerly direction until the landscape Agisymba. There are various considerations, what role Iulius Maternus had played during this expedition: he was seen as a Roman general, as a businessman or as a diplomat. Raffael Joorde -a german historian- wrote that Maternus was a diplomat who received the unique opportunity to make the extensive territory south of the Sahara accessible for the geographers in the Roman world probably reaching the Atlantic ocean in actual Nigeria. The cause of this long journey is assumed by many researchers to be a military campaign of the king of the Garamantes against rebellious subjects.

However some historians (like Susan Raven) believe that there was even another Roman expedition to sub-saharan central Africa: the one of Valerius Festus, that could have reached the equatorial Africa thanks to the Niger river.

Indeed Pliny wrote that in 70 AD a legatus of the Legio III Augusta named Festus repeated the Balbus expedition toward the Niger river. He went to the eastern Hoggar Mountains and the entered the Air Mountains as far as the Gadoufaoua plain. Gadoufaoua (Touareg for “the place where camels fear to go”) is a site in the Tenere desert of Niger known for its extensive fossil graveyard, where remains of Sarcosuchus imperator, popularly known as SuperCroc, have been found). Festus finally arrived in the area in which Timbuktu is now located.

Some academics, such as Fage, think that he only reached the Ghat region in southern Libya, near the border with southern Algeria and Niger. However, it is possible that a few of his legionaries reached as far as the Niger river and went down to the equatorial forests navigating the river to the delta estuary in what is now southern Nigeria. Something similar may have occurred in the exploration of the Nile done under Emperor Nero in Uganda.

After the third/fourth century the roman contacts with sub-saharan Africa started to disappear, because of the final crisis in the roman empire

Maritime travels

Even maritime contacts happened in the western coast of Africa: there are some academic discussions about the possibility of further Roman travels toward Guinea and Nigeria and even the equatorial areas of the Gulf of Guinea.

XIX century map showing the Fernando Po island in the Gulf of Guinea. This island was known to the Romans as one of the "Hesperides": they knew that it was located at 40 days of navigation from the Cape Verde islands (called in roman times "Gorgades")

Indeed according to Pliny the Elder and his citation by Gaius Julius Solinus, the sea voyaging time crossing from the Gorgades (Cape Verde islands) to the islands of the Ladies of the West ("Hesperides") now known as São Tomé and Príncipe and Fernando Po was around 40 days (meaning that Romans knew the exact time needed to reach these equatorial islands -located in front of Camerun/Niger delta- and only with their direct exploration/navigation they could have know this precise time).

Furthermore, a Roman coin -in a good condition- of the emperor Trajan has been found in Congo (http://www.strangehistory.net/2015/02/10/roman-coin-congo/).

Roman coins have been also found in Nigeria and Niger; and in Guinea, Togo and Ghana too. However, it is much more likely that all these coins were introduced at a much later date than that when there was direct Roman intercourse so far down the western coast. But it is possible -even if with a possibility of a very minimal percentage of only 5%, according to researchers- that Roman merchants left there those coins doing their trade when reached the gulf of Guinea.

Finally it is important to remember that Augustus, based on the discovery of a sunken roman merchant ship from southern Hispania in the Djibouti area (in the horn of eastern Africa), wanted to organize around Africa a roman maritime expedition (to be done initially by his adoptive son Gaius Caesar when he sailed from Egypt's Berenice toward Aden).

It was going to be done -around 2 AD- from southern Egypt to Mogador and Sala (in actual Morocco). But it seems that it never took place.

Saturday, October 1, 2022

MONTENEGRO BETRAYED AFTER WW1 (& UNITED TO YUGOSLAVIA)

Only a few books have been written about how the independent kingdom of Montenegro was united to Yugoslavia after WW1 against the wish of many Montenegrins (who made the famous "Christmass Uprising" in 1919). One very well written is the one by Alberto Becherelli with the title "Montenegro Betrayed: The Yugoslav Unification and the Controversial Inter-Allied Occupation".

It is noteworthy to pinpoint that the Italian government (initially also with France) tried to stop this unification, but with no results: France at the Peace Coneference of Paris accepted the unification in 1919, while Italy choose to get an agreement with the Treaty of Rapallo in november 1920 (when Yugoslavia accepted the borders in Venezia Giulia and Dalmatia in exchange of Italy's no more intervention against the Montenegro unification)

Later in the twentieth century, the "Christmas Uprising" was subject to ideological emphasis in Montenegrin nationalism. In World War II, one of the earliest leaders of the Greens, Sekula Drljević, invited the Italian occupation of Montenegro and collaborated with Italy in order to break away from Yugoslavia with the "Italian Governorate of Montenegro"(1941-1943). With him there was also Krsto Popović, the leader of the "Christmas uprising", who organized his collaboration militia called the "Lovćen Brigade". This militia was under the control or influence of the fascist Italian occupation force (if interested, please read: https://www.academia.edu/42722637/L_occupazione_italiana_in_Montenegro_Forme_di_guerriglia_e_dinamiche_politiche_del_collaborazionismo_%C4%8Detnico_1941_1943_Qualestoria_anno_XLIII_n_2_dicembre_2015_pp_65_80?email_work_card=view-paper).

The following are some excerpts from this very interesting book:

Montenegro Betrayed: The Yugoslav Unification

A Tradition of Independence

During WWI, the Kingdom of Montenegro experienced its last troubled period of independence at the end of a process that in the 19 th century had brought the country almost continuously in a stateof war against the Ottomans with important political and military successes, despite the fact that Sultan Selim III, already in 1799, had formally recognized that Montenegrins “had never been subjects of the High Porte.”

Under the Ottoman domination, the mountains of Montenegro preserved a de facto autonomy from the authority of the sultan due to a peculiar tribal structure and on the basis of the payment of a tribute, which frequently had been unpaid. A particulartheocracy headed by the prince bishop of Cetinje – vladika elected by a local assembly– had existed from the beginning of the 16th cen-tury until 1851, when Montenegro, after the death of Petar II Petrović-Njegoš (author of a literary work that became a symbol of the Montenegrin and more generally of the South Slavic nation-building process: Gorski Vijenac [The Mountain Wreath]) also became a secular principality with a definitive separation between temporal and spiritual power.

Over the centuries, the Ottoman army repeatedly attempted to subjugate without success the Montenegrin tribes from the mountains, while the Montenegrin cities on the coast remained for a long time linked to the "Serenissima" Venazia: if Bar (Antivari) and Ulcinj were conquered by the Ottomans in 1571, Kotor and the territory of oka (since 1420), and Budva (since 1442) remained Venetian until 1797 (and after the Napoleonic period under Austria until 1918).

From this historical legacy, the widespread belief among the 18th century Montenegrin vladikas was that Montenegro, whose independence was recognized at the Congress of Berlin of 1878, had never been fully conquered by the Turks.

Still at the beginning of the 20th century Montenegro, also due to the constantly increasing influence of Russia on the country in the previous two centuries, was at the forefront in the fight against “the oppressors of the Slavic peoples,” and the first among the Balkan allies to proclaim war on Turkey in October 1912. If in 1911, before the Balkan Wars, the territory of the kingdom had less than 10,000km with a population of 284,000 inhabitants, in 1914 the country’s surface reached 15,000 km and the population rose to 470,000 inhabitants.

Since 1860, King Nikola was the seventh sovereign from the Petrović-Njegoš dynasty (founded in 1697 by Vladika Danilo IPetrović) and during his fiftieth year (1910) of reign –with half a century of territorial expansion, modernization and socio-economic progress– the principality of Montenegro was elevated to a kingdom andBar declared a free port. Moreover, since December 1905 King Nikola had introduced in the country a constitution based on the Serbian one from 1869.Relations between Montenegrins and Serbs, in the years beforeand during WWI, were controversial.

On the one hand, the Yugo-slav idea had gradually unified the two peoples and, after the parti-tion of the Sandžak of Novi Pazar, proposals for a political, customsand military union of the two countries were advanced – despite the persistent divergences between the Petrović-Njegoš and Karađor-đević dynasties, both eager to make their own kingdoms the central pillar of the Yugoslav unification. On the other hand, the tradition ofindependence of Montenegro was still strong and solidified by therecent wars, which had contributed to strengthen the brotherhood between the Yugoslav peoples, but had not helped in improving therelations between the governments of Cetinje and Belgrade.

In this sense, the Montenegrins continued to reproach the Serbian attitudetowards their aspirations over Shkodër: both the Serbian abandon-ment of the siege during the Balkan Wars and the Serbian attemptduring the retreat at the end of 1915 to assume the control of the cityeven though it had been previously occupied by the Montenegrins.

The Shkodër area was one of the main territorial objectives for the expansion of Montenegro, together with Herzegovina, the south-eastern part of Bosnia, and the Adriatic coast from the spring of the Neretva River to the Bay of Kotor (former Cattaro), including Dubrovnik (former Ragusa).

In addition to this, during WWI, the Montenegrin Army was subject to the Serbian Army General Staff; for this reason the Montenegrins accused the Serbian officers in command for being responsible for the defeat. In October 1915, indeed, the resistance of the Montenegrin army against the offensive of the Austro-Hungarians was ineffective. As aconsequence, in January 1916, the latter had conquered Mount Lovćen and then had invaded the entire country. King Nikola fled to France and Montenegro fell under the Austro-Hungarian domination until the defeat and collapse of the Dual Monarchy in 1918.

Photo of Krsto Popovic, the leader of the Christmas Uprising: The Controversial Union with Serbia

Far from becoming an independent state again, Montenegro at the end of the war was occupied by the Serbian troops. With the Corfu Declaration of July 20, 1917, the head of the Serbian government Nikola Pašić and the leader of the Yugoslav Committee Ante Trumbić had already laid the basis of the Yugoslav union. The unification of the South Slavic territories with the Kingdom of Serbia was agreed by Pašić, some members of the Skupština, the representatives of the National Council of Zagreb and those of the Yugoslav Committee with the Geneva Convention of November 9, 1918.

With the occupation of Montenegro by the Allied troops –French, British, American and Italian– in the autumn of 1918 most of the country went under the control of the Serbian troops of Colonel Dragutin Milutinović, that presented themselves as the redeemers of the “oppressed brothers” and were actively engaged in propagating the union between Montenegro and Serbia. The unification was supported by relevant Montenegrin personalities such as Andrija Radović, head of the government in exile until January 1917. The split between Radović and King Nikola had lasted since August 1916, when the prime minister of Montenegro started supporting the union of Serbia and Montenegro through the unification of the Petrović-Njegoš and Karađorđević dynasties, firstly with the abdication of the former in favor of Alexander of Serbia, and then with a following rotation tothe throne between the two families.

Since February 1917, Radović was leading the Montenegrin Committee for the National Unifica-tion, founded in Geneva and in close contact with the Serbian governmental circles that worked to de-legitimize the sovereignty of King Nikola over Montenegro.At this point, the Montenegrin sovereign, mainly due to the marriage of his daughter Elena with the King of Italy Vittorio Emanuele III, hoped that the Italian occupation of Kotor and Bar could counterbalance the Serbian one and in some way be useful for the preservation of his dynasty on the throne of Montenegro. The Italian ambitions on the other side of the Adriatic Sea, a mix of political, strategic and economic aspirations, at least were the best guarantee for the maintenance of Montenegrin independence. At a political level, however, the Serbian Prime Minister Pašić worked to legalize the Serbian hegemony over the territory of Montenegro, preventing the return of King Nikola to the country, dissuaded also by the Italian and French governments.

At the same time, the committee led byRadović began the campaign for the election of the deputies to theGreat National Assembly in Podgorica, which would decide on the future status of Montenegro. On November 19, 1918, the Montenegrin elections held under the military pressure of the Serbian troops were done by acclamation rather than secret vote. Cetinje was the center of political propaganda: here the supporters of the unconditioned union with Serbia presented a list of candidates on a white colored paper, while their opponents, more cautious and with the aim to preserve the political integrity of Montenegro, presented a green colored list.

The two colors became the terms used to identify the two factions: the “whites”(bjelaši) were favorable to the union with Serbia, and the “greens”(zelenaši) were the supporters of independence. If the latter were pri-marily an expression of the rural society, the former had among theirranks more urban exponents: merchants, artisans, and intellectuals.

The Inter-Allied Occupation and the "Christmas Uprising"

According to the Italian military authorities in Montenegro, from the end of December 1918 there were rumors that in order to provide for the shortage of armament the Italian garrisons of Virpazar and Bar could be attacked both by pro-Serbian armed movements and Montenegrin independence supporters. This was the premise of the anti-Serb uprising that began in the surroundings of Cetinje on January 3, 1919. Jovan Simonov Plamenac and the other “green” leaders sent emissaries to the Inter-Allied command of Cattaro, led by the French General Venel, to demand the occupation of Cetinje and Montenegro by the Inter-Allied troops with the exclusion of the Serbian-Yugoslav ones.

Even in Bar the goal of the insurgents was to throwout the pro-Serbian local authorities. For Venel, however, any kind of Inter-Allied intervention against the Serbian-Yugoslav troops wasout of discussion. As in the previous days, the French general in charge did not even consult the commanders of the other Alliedcontingents. The French seemed deliberately favoring the Serbian occupation, openly supporting Radović and the “white” faction inthe area between Virpazar and Shkodër and facilitating the arrival rom Dubrovnik of a pro-Serbian Montenegrin legion trained and supported by the French.

The Italian military command in Montenegro openly denounced the pro-Serbian attitude of the French, an accusation that was considered reliable also by the American Ambassador in Rome Nelson Page, who on January 9 reported to the Commission to Negotiate Peace in Paris the text of a telegram from Kotor which stated:

........"January 6: French General is making a French-Serbian penetration into Montenegro admitting no other than Serbian authority. The intervention of his troops has a counterrevolutionary character. There are about 3,000 of which 500 were landed at Ragusa, 400 of the latter having already arrived at Cattaro [Kotor] have gone into Montenegro in French uniforms and with Serbo-French officers. Immediate help and energetic diplomatic steps indispensable since the enemy is energetically stirring up sedition.".......

Even the Montenegrin government in exile condemned how the French authorities facilitated the arrival in Montenegro of the followers of Radović, at the same time hindering the arrival of King Nikola’s supporters to whom had been denied the permission to enter the country with trivial excuses.

The Italians suspected that even the health precautions taken by the French in Kotor against typhoid cases in late December –communication between the city and the rest of Montenegro was limited with a release of a safe-conduct forleaving the country– were a pretext in order to allow to the Serbian commands to isolate the Montenegrin population. Pero Šoć denounced this attempt by the Serbian authorities to the American chargè d’affaires in France Bliss. According to Šoć only Serbian conspirators and agents had open access to Montenegro, while Montenegrin statesmen and politicians had to appeal to the Allies in order to have the permission to leave the country and reach Rome or Paris.

For this reason, the Italian general accused the French command of complicity in the subjugation of the Montenegrin population perpetrated by the Serbian authorities. Even without the support of the Inter-Allied authorities, Montenegrin insurgents under the command of Krsto Popovic (around 15,000-20,000 persons in the whole country) marched on Cetinje and other cities (Nikšić, Virpazar, Podgorica) facing Serbian-Yugoslav troops (January 6), which had a smaller number of men but were better equipped. Lacking food and ammunition, military preparation, skills and resolute leaders, around 3,500 “greens,” of which only a third were armed, were soon forced to desist from taking Cetinje, the only city where for a few days the insurgents could engage into a real battle against the Serbian-Yugoslav soldiers (400 men) and the “white” militias (300 men) under the command of the Serbian general Martinović.

Although they had the support of the population who were opposed to the violence of the “whites” and to the unconditional union of Montenegro with Serbia carried out in terms of a simple annexation, the “greens” did not prove to be as organized and cohesive as their opponents and the Serbian-Yugoslav soldiers were. The goal of the “green” armed insurrection was mainly to provoke an Allied intervention, and in particular an Italian one also if they had never explicitly affirmed it; it was not a real movement of resistance. The neutral position of the Italian troops, from which the insurgents expected a more or less direct support, diminished the hope of the “greens” for a success.

After the failed rebellion, despite the assurances given by Venel, the Serbs launched retaliation. Only in Podgorica they arrested 164 persons, including three cousins of King Nikola, eighty officers and numerous dignitaries of the court, confiscating properties.

The conflict between the “greens” and “whites,” however, did not end with the uprising of January 1919 and continued in the following years. The Italian military authorities, in the areas under their occupation, recorded incidents and violence between the “whites” and the Serbian-Yugoslav troops on the one side and Montenegrin nationalist gangs on the other. In early June, for example, the Italian High Command and the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs received reports about clashes in the mountainous region of the Shkodër frontier (Skadarska Krajina, Krajë for the Albanians) between the Serbian-Yugoslav troops and the Montenegrin "Komiti" headed by the well-known Savo Raspopović, on whose head the Serbian authorities placed a bounty of 20,000 dinars. Only in the evening of May 27, the assault of the bands of Raspopović caused to the Serbian-Yugoslavs several causalities. During the month, Raspopović continued his attacks in the area around Bar, a fact that brought the Serbian-Yugo-slav troops to accuse the Italians of having reached an agreement with the Montenegrin leader.

At the same time, Italian soldiers had to face frequent clashes with the Serbian-Yugoslav units and militias, which often ended in gun-fight for not entirely clear reasons.

The head of the Italian Army General Staff also insinuated that the French command in Albania and Montenegro could be responsible for many of the increasingly frequent anti-Italian demonstrations in the country. The Italian Foreign Minister Tommaso Tittoni promised to bring to the attention ofthe Allied governments the attitude of the Serbian-Yugoslavs, who claimed at all costs that Italian troops should abandon Montenegro.

The garrisons in the country, including the Italian detachments, were abandoned by the Allied troops at the end of April 1919. The Allied occupation was reduced to the coastal area (Bar, Kotor, Ulcinj and Virpazar) withthe aim of securing the supplies for Shkodër, while the inner part of the country was garrisoned exclusively by the Serbian-Yugoslav troops. The English also left Virpazar and Bar between April 27 and 30. The Italians remained in Bar (at the railways and the port), Ko\tor and Virpazar and were categorically ordered not to be meddle inthe clashes between Serbian and Montenegrin “dissident” bands.

From the summer of 1919 indeed the “greens” again took up the arms, this time with the Italian support. In April, in fact, the government in Rome with the Montenegrin government in exile signed a military convention for the formation of a Montenegrin legion in Italy. The Italian ships landed in Montenegro with new forces ready to incite the population against the Serbian authorities without reaching the desired results. The regions of Bar and Virpazar became theaters of new conflicts between Serbian-Yugoslavs, Montenegrin rebels and Italian troops.

The Yugoslav delegation at the Paris Peace Conference, indeed, once again explicitly asked for the evacuation of the Italian troops from Montenegro to definitely complete the unification of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. In the summer of 1919, Radović (July 26-29) and then Pašić (August 14, 29 and 31) sent notes to the french Clemenceau calling for the withdrawal of the Italian troops that were accused of intentionally encouraging “the elements of disorder” in Montenegro.

Flags of the Green montenegrins while in exile in Gaeta (Italy):

Conclusions

At the end of 1919, at the Paris Peace Conference, the Yugoslav delegation –as during the summer the Italian counterpart had already done– officially denounced a series of violence that the Italian command in Montenegro committed against the Yugoslav soldiers and civilians and for which a special committee was appointed by the government of Belgrade for investigation. On the other hand, the Allies communicated to the Montenegrin government in exile that they no longer would anticipate the monthly credit hitherto paid to King Nikola (the subsidies ceased at the end of October).

In this way, King Nikola was forced to leave Paris and to reach Prince anilo, while the Montenegrin government in exile had to reduce its personnel, leaving in Neuilly sur Seine only Plamenac and other few persons. In this situation, despite the hostility of the Montenegrin population to the Serbian annexation, which, as it had already been said, did not mean an opposition to a real Yugoslav federalist union, or the Montenegrin establishment in exile it was impossible to continue to support the historical rights of Montenegro for independence.

Among other things, Plamenac tried a series of desperate and unsuccessful initiatives, such as the agreement concluded on May 12, 1920, with Gabriele D’Annunzio, who was still in Fiume with his legionaries, hoping to keep some kind of Italian support for the Montenegrin issue. At that time, in fact, the Italian government for the resolution of the Adriatic question had already abandoned the previous political radicalism and was now ready to reach an agreement with the government of Belgrade. The agreement of Plamenac and D’Annunzio, with the latter that was keeping contacts with the representatives of the Yugoslav nationalities that opposed Belgrade centralism in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, provided for the restoration of the independence of the Montenegrin kingdom as a first step towards the liberation of the Yugoslav populations from the Serbian rule.

The Supreme Council of the Allies briefly examined only a Mon-tenegrin note sent on November 26, 1919, with which Plamenac threatened that if the Montenegrin delegate was not immediately invited to the Peace Conference for the signing of the peace treaties with Germany, Austria and Bulgaria, the Montenegrin government in exile would conclude a separate peace with these countries.

On December 1, 1919, the Supreme Council decided not to give any response to the threats of Plamenac, simply ignoring his letter. The Italian delegate De Martino agreed with the decision, but also asked if the Supreme Council before or later would take into consideration the Montenegrin issue, which still needed a solution. For Clemenceau the Montenegrin issue did not exist, the problem –he replied to De Martino– was more over different: For how long did the Italian government still have the intention to pursue this matter? Clemenceau, without explicitly stating it, was reaffirming that for the Allies the Montenegrin issue had been resolved long time ago with the proclamation of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

he Montenegrin issue, from the diplomatic point of view, was officially over at the end of 1920, when also the appeals of the Montenegrin government in exile to the League of Nations did not find an answer (November 1920).

Italy, which had been the main supporter of the Montenegrin cause in order to defend its interests on the other coast of the Adriatic Sea against the Yugoslav aspirations, finally interrupted the political and military support to the Montenegrin refugees preferring an agreement with the Kingdom of Yugoslavia for the definition of the border dispute and other controversial issues. The signing of the Treaty of Rapallo, in November 1920, meant the definitive end of the Montenegrin issue and the legitimacy of the Yugoslav state for the country that had opposed the most its recognition in the international context.

After the apparent settlement of the Adriatic issue and of the Italian-Yugoslav relations, also France took the moment to resolve itsrelations with the Montenegrin king (on December 20, 1920).

Even for Great Britain, which still during the summer of 1920 had refused to recognize the annexation of Montenegro as a fait accompli – Vesnić, head of the government in Belgrade, was insisting on this argument for the formal recognition of the union of Montenegro with the Kingdom SHS– the opportunity for the Montenegrin people to send “freely elected representatives to the Yugoslav Constituent Assembly” represented the best recognition of the legitimacy of the unification.

All this facts were followed by the interruption of diplomatic relations between the Montenegrin government in exile –that in the meantime was moved to Rome– and the United States and Great Britain respectively on January 21 and March 17, 1921: it was substantially the conclusion of the vain struggle for the independence of Montenegro against the unconditional union with Serbia and the final acceptance of its incorporation into the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

Further readings

1-Montenegro italiano (1941-1943): https://www.academia.edu/6469238/le_nuove_province

2-Occupazione italiana dell'Adriatico dalmato nel 1918: https://www.eastjournal.net/archives/126261

It is noteworthy to pinpoint that the Italian government (initially also with France) tried to stop this unification, but with no results: France at the Peace Coneference of Paris accepted the unification in 1919, while Italy choose to get an agreement with the Treaty of Rapallo in november 1920 (when Yugoslavia accepted the borders in Venezia Giulia and Dalmatia in exchange of Italy's no more intervention against the Montenegro unification)

Later in the twentieth century, the "Christmas Uprising" was subject to ideological emphasis in Montenegrin nationalism. In World War II, one of the earliest leaders of the Greens, Sekula Drljević, invited the Italian occupation of Montenegro and collaborated with Italy in order to break away from Yugoslavia with the "Italian Governorate of Montenegro"(1941-1943). With him there was also Krsto Popović, the leader of the "Christmas uprising", who organized his collaboration militia called the "Lovćen Brigade". This militia was under the control or influence of the fascist Italian occupation force (if interested, please read: https://www.academia.edu/42722637/L_occupazione_italiana_in_Montenegro_Forme_di_guerriglia_e_dinamiche_politiche_del_collaborazionismo_%C4%8Detnico_1941_1943_Qualestoria_anno_XLIII_n_2_dicembre_2015_pp_65_80?email_work_card=view-paper).

The following are some excerpts from this very interesting book:

Montenegro Betrayed: The Yugoslav Unification

A Tradition of Independence

During WWI, the Kingdom of Montenegro experienced its last troubled period of independence at the end of a process that in the 19 th century had brought the country almost continuously in a stateof war against the Ottomans with important political and military successes, despite the fact that Sultan Selim III, already in 1799, had formally recognized that Montenegrins “had never been subjects of the High Porte.”

Under the Ottoman domination, the mountains of Montenegro preserved a de facto autonomy from the authority of the sultan due to a peculiar tribal structure and on the basis of the payment of a tribute, which frequently had been unpaid. A particulartheocracy headed by the prince bishop of Cetinje – vladika elected by a local assembly– had existed from the beginning of the 16th cen-tury until 1851, when Montenegro, after the death of Petar II Petrović-Njegoš (author of a literary work that became a symbol of the Montenegrin and more generally of the South Slavic nation-building process: Gorski Vijenac [The Mountain Wreath]) also became a secular principality with a definitive separation between temporal and spiritual power.

Over the centuries, the Ottoman army repeatedly attempted to subjugate without success the Montenegrin tribes from the mountains, while the Montenegrin cities on the coast remained for a long time linked to the "Serenissima" Venazia: if Bar (Antivari) and Ulcinj were conquered by the Ottomans in 1571, Kotor and the territory of oka (since 1420), and Budva (since 1442) remained Venetian until 1797 (and after the Napoleonic period under Austria until 1918).

From this historical legacy, the widespread belief among the 18th century Montenegrin vladikas was that Montenegro, whose independence was recognized at the Congress of Berlin of 1878, had never been fully conquered by the Turks.

Still at the beginning of the 20th century Montenegro, also due to the constantly increasing influence of Russia on the country in the previous two centuries, was at the forefront in the fight against “the oppressors of the Slavic peoples,” and the first among the Balkan allies to proclaim war on Turkey in October 1912. If in 1911, before the Balkan Wars, the territory of the kingdom had less than 10,000km with a population of 284,000 inhabitants, in 1914 the country’s surface reached 15,000 km and the population rose to 470,000 inhabitants.

Since 1860, King Nikola was the seventh sovereign from the Petrović-Njegoš dynasty (founded in 1697 by Vladika Danilo IPetrović) and during his fiftieth year (1910) of reign –with half a century of territorial expansion, modernization and socio-economic progress– the principality of Montenegro was elevated to a kingdom andBar declared a free port. Moreover, since December 1905 King Nikola had introduced in the country a constitution based on the Serbian one from 1869.Relations between Montenegrins and Serbs, in the years beforeand during WWI, were controversial.

On the one hand, the Yugo-slav idea had gradually unified the two peoples and, after the parti-tion of the Sandžak of Novi Pazar, proposals for a political, customsand military union of the two countries were advanced – despite the persistent divergences between the Petrović-Njegoš and Karađor-đević dynasties, both eager to make their own kingdoms the central pillar of the Yugoslav unification. On the other hand, the tradition ofindependence of Montenegro was still strong and solidified by therecent wars, which had contributed to strengthen the brotherhood between the Yugoslav peoples, but had not helped in improving therelations between the governments of Cetinje and Belgrade.

In this sense, the Montenegrins continued to reproach the Serbian attitudetowards their aspirations over Shkodër: both the Serbian abandon-ment of the siege during the Balkan Wars and the Serbian attemptduring the retreat at the end of 1915 to assume the control of the cityeven though it had been previously occupied by the Montenegrins.

The Shkodër area was one of the main territorial objectives for the expansion of Montenegro, together with Herzegovina, the south-eastern part of Bosnia, and the Adriatic coast from the spring of the Neretva River to the Bay of Kotor (former Cattaro), including Dubrovnik (former Ragusa).

In addition to this, during WWI, the Montenegrin Army was subject to the Serbian Army General Staff; for this reason the Montenegrins accused the Serbian officers in command for being responsible for the defeat. In October 1915, indeed, the resistance of the Montenegrin army against the offensive of the Austro-Hungarians was ineffective. As aconsequence, in January 1916, the latter had conquered Mount Lovćen and then had invaded the entire country. King Nikola fled to France and Montenegro fell under the Austro-Hungarian domination until the defeat and collapse of the Dual Monarchy in 1918.

Photo of Krsto Popovic, the leader of the Christmas Uprising: The Controversial Union with Serbia

Far from becoming an independent state again, Montenegro at the end of the war was occupied by the Serbian troops. With the Corfu Declaration of July 20, 1917, the head of the Serbian government Nikola Pašić and the leader of the Yugoslav Committee Ante Trumbić had already laid the basis of the Yugoslav union. The unification of the South Slavic territories with the Kingdom of Serbia was agreed by Pašić, some members of the Skupština, the representatives of the National Council of Zagreb and those of the Yugoslav Committee with the Geneva Convention of November 9, 1918.

With the occupation of Montenegro by the Allied troops –French, British, American and Italian– in the autumn of 1918 most of the country went under the control of the Serbian troops of Colonel Dragutin Milutinović, that presented themselves as the redeemers of the “oppressed brothers” and were actively engaged in propagating the union between Montenegro and Serbia. The unification was supported by relevant Montenegrin personalities such as Andrija Radović, head of the government in exile until January 1917. The split between Radović and King Nikola had lasted since August 1916, when the prime minister of Montenegro started supporting the union of Serbia and Montenegro through the unification of the Petrović-Njegoš and Karađorđević dynasties, firstly with the abdication of the former in favor of Alexander of Serbia, and then with a following rotation tothe throne between the two families.

Since February 1917, Radović was leading the Montenegrin Committee for the National Unifica-tion, founded in Geneva and in close contact with the Serbian governmental circles that worked to de-legitimize the sovereignty of King Nikola over Montenegro.At this point, the Montenegrin sovereign, mainly due to the marriage of his daughter Elena with the King of Italy Vittorio Emanuele III, hoped that the Italian occupation of Kotor and Bar could counterbalance the Serbian one and in some way be useful for the preservation of his dynasty on the throne of Montenegro. The Italian ambitions on the other side of the Adriatic Sea, a mix of political, strategic and economic aspirations, at least were the best guarantee for the maintenance of Montenegrin independence. At a political level, however, the Serbian Prime Minister Pašić worked to legalize the Serbian hegemony over the territory of Montenegro, preventing the return of King Nikola to the country, dissuaded also by the Italian and French governments.

At the same time, the committee led byRadović began the campaign for the election of the deputies to theGreat National Assembly in Podgorica, which would decide on the future status of Montenegro. On November 19, 1918, the Montenegrin elections held under the military pressure of the Serbian troops were done by acclamation rather than secret vote. Cetinje was the center of political propaganda: here the supporters of the unconditioned union with Serbia presented a list of candidates on a white colored paper, while their opponents, more cautious and with the aim to preserve the political integrity of Montenegro, presented a green colored list.

The two colors became the terms used to identify the two factions: the “whites”(bjelaši) were favorable to the union with Serbia, and the “greens”(zelenaši) were the supporters of independence. If the latter were pri-marily an expression of the rural society, the former had among theirranks more urban exponents: merchants, artisans, and intellectuals.

The Inter-Allied Occupation and the "Christmas Uprising"

According to the Italian military authorities in Montenegro, from the end of December 1918 there were rumors that in order to provide for the shortage of armament the Italian garrisons of Virpazar and Bar could be attacked both by pro-Serbian armed movements and Montenegrin independence supporters. This was the premise of the anti-Serb uprising that began in the surroundings of Cetinje on January 3, 1919. Jovan Simonov Plamenac and the other “green” leaders sent emissaries to the Inter-Allied command of Cattaro, led by the French General Venel, to demand the occupation of Cetinje and Montenegro by the Inter-Allied troops with the exclusion of the Serbian-Yugoslav ones.

Even in Bar the goal of the insurgents was to throwout the pro-Serbian local authorities. For Venel, however, any kind of Inter-Allied intervention against the Serbian-Yugoslav troops wasout of discussion. As in the previous days, the French general in charge did not even consult the commanders of the other Alliedcontingents. The French seemed deliberately favoring the Serbian occupation, openly supporting Radović and the “white” faction inthe area between Virpazar and Shkodër and facilitating the arrival rom Dubrovnik of a pro-Serbian Montenegrin legion trained and supported by the French.

The Italian military command in Montenegro openly denounced the pro-Serbian attitude of the French, an accusation that was considered reliable also by the American Ambassador in Rome Nelson Page, who on January 9 reported to the Commission to Negotiate Peace in Paris the text of a telegram from Kotor which stated:

........"January 6: French General is making a French-Serbian penetration into Montenegro admitting no other than Serbian authority. The intervention of his troops has a counterrevolutionary character. There are about 3,000 of which 500 were landed at Ragusa, 400 of the latter having already arrived at Cattaro [Kotor] have gone into Montenegro in French uniforms and with Serbo-French officers. Immediate help and energetic diplomatic steps indispensable since the enemy is energetically stirring up sedition.".......

Even the Montenegrin government in exile condemned how the French authorities facilitated the arrival in Montenegro of the followers of Radović, at the same time hindering the arrival of King Nikola’s supporters to whom had been denied the permission to enter the country with trivial excuses.

The Italians suspected that even the health precautions taken by the French in Kotor against typhoid cases in late December –communication between the city and the rest of Montenegro was limited with a release of a safe-conduct forleaving the country– were a pretext in order to allow to the Serbian commands to isolate the Montenegrin population. Pero Šoć denounced this attempt by the Serbian authorities to the American chargè d’affaires in France Bliss. According to Šoć only Serbian conspirators and agents had open access to Montenegro, while Montenegrin statesmen and politicians had to appeal to the Allies in order to have the permission to leave the country and reach Rome or Paris.

For this reason, the Italian general accused the French command of complicity in the subjugation of the Montenegrin population perpetrated by the Serbian authorities. Even without the support of the Inter-Allied authorities, Montenegrin insurgents under the command of Krsto Popovic (around 15,000-20,000 persons in the whole country) marched on Cetinje and other cities (Nikšić, Virpazar, Podgorica) facing Serbian-Yugoslav troops (January 6), which had a smaller number of men but were better equipped. Lacking food and ammunition, military preparation, skills and resolute leaders, around 3,500 “greens,” of which only a third were armed, were soon forced to desist from taking Cetinje, the only city where for a few days the insurgents could engage into a real battle against the Serbian-Yugoslav soldiers (400 men) and the “white” militias (300 men) under the command of the Serbian general Martinović.

Although they had the support of the population who were opposed to the violence of the “whites” and to the unconditional union of Montenegro with Serbia carried out in terms of a simple annexation, the “greens” did not prove to be as organized and cohesive as their opponents and the Serbian-Yugoslav soldiers were. The goal of the “green” armed insurrection was mainly to provoke an Allied intervention, and in particular an Italian one also if they had never explicitly affirmed it; it was not a real movement of resistance. The neutral position of the Italian troops, from which the insurgents expected a more or less direct support, diminished the hope of the “greens” for a success.

After the failed rebellion, despite the assurances given by Venel, the Serbs launched retaliation. Only in Podgorica they arrested 164 persons, including three cousins of King Nikola, eighty officers and numerous dignitaries of the court, confiscating properties.

The conflict between the “greens” and “whites,” however, did not end with the uprising of January 1919 and continued in the following years. The Italian military authorities, in the areas under their occupation, recorded incidents and violence between the “whites” and the Serbian-Yugoslav troops on the one side and Montenegrin nationalist gangs on the other. In early June, for example, the Italian High Command and the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs received reports about clashes in the mountainous region of the Shkodër frontier (Skadarska Krajina, Krajë for the Albanians) between the Serbian-Yugoslav troops and the Montenegrin "Komiti" headed by the well-known Savo Raspopović, on whose head the Serbian authorities placed a bounty of 20,000 dinars. Only in the evening of May 27, the assault of the bands of Raspopović caused to the Serbian-Yugoslavs several causalities. During the month, Raspopović continued his attacks in the area around Bar, a fact that brought the Serbian-Yugo-slav troops to accuse the Italians of having reached an agreement with the Montenegrin leader.

At the same time, Italian soldiers had to face frequent clashes with the Serbian-Yugoslav units and militias, which often ended in gun-fight for not entirely clear reasons.

The head of the Italian Army General Staff also insinuated that the French command in Albania and Montenegro could be responsible for many of the increasingly frequent anti-Italian demonstrations in the country. The Italian Foreign Minister Tommaso Tittoni promised to bring to the attention ofthe Allied governments the attitude of the Serbian-Yugoslavs, who claimed at all costs that Italian troops should abandon Montenegro.

The garrisons in the country, including the Italian detachments, were abandoned by the Allied troops at the end of April 1919. The Allied occupation was reduced to the coastal area (Bar, Kotor, Ulcinj and Virpazar) withthe aim of securing the supplies for Shkodër, while the inner part of the country was garrisoned exclusively by the Serbian-Yugoslav troops. The English also left Virpazar and Bar between April 27 and 30. The Italians remained in Bar (at the railways and the port), Ko\tor and Virpazar and were categorically ordered not to be meddle inthe clashes between Serbian and Montenegrin “dissident” bands.

From the summer of 1919 indeed the “greens” again took up the arms, this time with the Italian support. In April, in fact, the government in Rome with the Montenegrin government in exile signed a military convention for the formation of a Montenegrin legion in Italy. The Italian ships landed in Montenegro with new forces ready to incite the population against the Serbian authorities without reaching the desired results. The regions of Bar and Virpazar became theaters of new conflicts between Serbian-Yugoslavs, Montenegrin rebels and Italian troops.

The Yugoslav delegation at the Paris Peace Conference, indeed, once again explicitly asked for the evacuation of the Italian troops from Montenegro to definitely complete the unification of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. In the summer of 1919, Radović (July 26-29) and then Pašić (August 14, 29 and 31) sent notes to the french Clemenceau calling for the withdrawal of the Italian troops that were accused of intentionally encouraging “the elements of disorder” in Montenegro.

Flags of the Green montenegrins while in exile in Gaeta (Italy):

Conclusions

At the end of 1919, at the Paris Peace Conference, the Yugoslav delegation –as during the summer the Italian counterpart had already done– officially denounced a series of violence that the Italian command in Montenegro committed against the Yugoslav soldiers and civilians and for which a special committee was appointed by the government of Belgrade for investigation. On the other hand, the Allies communicated to the Montenegrin government in exile that they no longer would anticipate the monthly credit hitherto paid to King Nikola (the subsidies ceased at the end of October).

In this way, King Nikola was forced to leave Paris and to reach Prince anilo, while the Montenegrin government in exile had to reduce its personnel, leaving in Neuilly sur Seine only Plamenac and other few persons. In this situation, despite the hostility of the Montenegrin population to the Serbian annexation, which, as it had already been said, did not mean an opposition to a real Yugoslav federalist union, or the Montenegrin establishment in exile it was impossible to continue to support the historical rights of Montenegro for independence.

Among other things, Plamenac tried a series of desperate and unsuccessful initiatives, such as the agreement concluded on May 12, 1920, with Gabriele D’Annunzio, who was still in Fiume with his legionaries, hoping to keep some kind of Italian support for the Montenegrin issue. At that time, in fact, the Italian government for the resolution of the Adriatic question had already abandoned the previous political radicalism and was now ready to reach an agreement with the government of Belgrade. The agreement of Plamenac and D’Annunzio, with the latter that was keeping contacts with the representatives of the Yugoslav nationalities that opposed Belgrade centralism in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, provided for the restoration of the independence of the Montenegrin kingdom as a first step towards the liberation of the Yugoslav populations from the Serbian rule.

The Supreme Council of the Allies briefly examined only a Mon-tenegrin note sent on November 26, 1919, with which Plamenac threatened that if the Montenegrin delegate was not immediately invited to the Peace Conference for the signing of the peace treaties with Germany, Austria and Bulgaria, the Montenegrin government in exile would conclude a separate peace with these countries.

On December 1, 1919, the Supreme Council decided not to give any response to the threats of Plamenac, simply ignoring his letter. The Italian delegate De Martino agreed with the decision, but also asked if the Supreme Council before or later would take into consideration the Montenegrin issue, which still needed a solution. For Clemenceau the Montenegrin issue did not exist, the problem –he replied to De Martino– was more over different: For how long did the Italian government still have the intention to pursue this matter? Clemenceau, without explicitly stating it, was reaffirming that for the Allies the Montenegrin issue had been resolved long time ago with the proclamation of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

he Montenegrin issue, from the diplomatic point of view, was officially over at the end of 1920, when also the appeals of the Montenegrin government in exile to the League of Nations did not find an answer (November 1920).

Italy, which had been the main supporter of the Montenegrin cause in order to defend its interests on the other coast of the Adriatic Sea against the Yugoslav aspirations, finally interrupted the political and military support to the Montenegrin refugees preferring an agreement with the Kingdom of Yugoslavia for the definition of the border dispute and other controversial issues. The signing of the Treaty of Rapallo, in November 1920, meant the definitive end of the Montenegrin issue and the legitimacy of the Yugoslav state for the country that had opposed the most its recognition in the international context.

After the apparent settlement of the Adriatic issue and of the Italian-Yugoslav relations, also France took the moment to resolve itsrelations with the Montenegrin king (on December 20, 1920).

Even for Great Britain, which still during the summer of 1920 had refused to recognize the annexation of Montenegro as a fait accompli – Vesnić, head of the government in Belgrade, was insisting on this argument for the formal recognition of the union of Montenegro with the Kingdom SHS– the opportunity for the Montenegrin people to send “freely elected representatives to the Yugoslav Constituent Assembly” represented the best recognition of the legitimacy of the unification.

All this facts were followed by the interruption of diplomatic relations between the Montenegrin government in exile –that in the meantime was moved to Rome– and the United States and Great Britain respectively on January 21 and March 17, 1921: it was substantially the conclusion of the vain struggle for the independence of Montenegro against the unconditional union with Serbia and the final acceptance of its incorporation into the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

Further readings

1-Montenegro italiano (1941-1943): https://www.academia.edu/6469238/le_nuove_province

2-Occupazione italiana dell'Adriatico dalmato nel 1918: https://www.eastjournal.net/archives/126261

Sunday, September 4, 2022

ITALIAN CATTARO (ACTUAL KOTOR IN MONTENEGRO)

In the south of coastal Dalmatia there it is a city that has a history closely linked to Italy: Cattaro, the actual "Kotor" (former capital of Montenegro). Indeed Cattaro -after being under the Republic of Venice for many centuries- has been "italian" two times in the last two centuries: in the napoleonic kingdom of Italy (1805-1810) and during WW2 (1941-1943). The following is an essay I have written in 2018 and that has been published -partially- on the english, spanish & italian wikipedia:

HISTORY OF "CATTARO" (actual Kotor, the main city of Montenegro)

Cattaro (or Venetian Cattaro, called in Italian "Cattaro la Veneziana") was the historical city populated by autochtonous "romanised" Dalmatians since the fall of the Roman empire and that belonged to the Republic of Venice for nearly five centuries until Napoleon times (for further info, please read my https://researchomnia.blogspot.com/2013/09/dalmatias-neolatin-city-states.html).

Later it was part of the Napoleonic kingdom of Italy until was added to the Austrian empire in the XIX century and started to lose the neolatin characteristics, while becoming a Montenegrin city called "Kotor" actually. However in 1941 the city was united for a few years to the Kingdom of Italy in the "Governorate of Dalmatia".

History

Ascrivium, or Ascruvium, the modern Cattaro, was first historically mentioned when submitted to Rome in 168 BC.

The "Dalmatian city-states", with own neolatin dialects (the main where in Veglia and Ragusa), showing Cattaro in southern Dalmatia

Roman emperor Justinian built a fortress above Ascrivium in AD 535, after expelling the Goths. The city had around 5000 inhabitants in that century.

A second town probably grew up on the heights around it, because Constantine Porphyrogenitus -in the 10th century- alluded to a "Lower Cattaro". The city suffered the barbarian invasions of the Avars and Slavs, but survived with the autochtonous romanised population greatly diminished to a few hundred inhabitants.

Cattaro was one of the more influential Dalmatian city-states of romanized Illyrians throughout the Middle Ages, and until the 11th century the Dalmatian language was spoken by the inhabitants of the city. Later, with the Venetian domination the inhabitants started to speak the "Veneto da mar" instead of the old Dalmatian language (until the XIX century, when the main language started to be the Montenegrin).

The city was plundered by the Saracens in 840 AD, and a few centuries later by the Bulgarians in 1102 AD. In the next year it was ceded to Serbia by the Bulgarian tsar Samuel, but revolted, in alliance with Ragusa, and only submitted in 1184 AD, as a protected state, preserving intact its republican institutions, and its right to conclude treaties and engage in war. It was already an "Episcopal See", and, in the 13th century, Dominican and Franciscan monasteries were established to check the spread of Bogomilism.

In the 14th century the commerce of Cattaro rivalled that of Ragusa, and provoked the jealousy of Venice. The downfall of Serbia in 1389 left the city without a guardian, and, after being seized and abandoned by Venice and Hungary in turn, it passed under Venetian rule in 1420. Since then, for nearly five centuries the city was called "Cattaro la Veneziana" (the venetian Cattaro), because it was a city fully Italian in architecture and literature and the majority of the inhabitants spoke the "Veneto da mar" Italian dialect (very similar to the one spoken in Istria). Cattaro in those centuries enjoyed a huge development and was the main city and capital of the "Albania Veneta".

Venetian Cattaro was a catholic city, with the territory of the Diocese that even today corresponds to that of the historical region Albania Veneta since 1571. Cattaro was the most eastern city of Catholicism in the Balkans dominated by the Ottomans: it was the symbol of western society successfully facing Muslim attacks in those centuries.

However it was besieged by the Turks in 1538 and 1657 but saved by the venetian fleet; visited by plague in 1572 and nearly destroyed by earthquakes in 1563 and 1667.

The Republic of Venice reconstructed Cattaro after the terrible earthquake of 1667 (https://www.total-montenegro-news.com/lifestyle/1247-italy-invests-in-its-cultural-heritage-in-boka-bay).

By the Treaty of Campoformio in 1797 it passed to Austria; but in 1805 -by the treaty of Pressburg- Cattaro was assigned to the kingdom of Italy (1) and later was united in 1810 with the first French Empire.

Venetian Maritime Gate in the Cattaro city-walls

Napoleon included Cattaro between 1805 and 1810 in his "Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy". and made a decree establishing the use of the Italian language in schools throughout Dalmatia.

Cattaro was nearly fully venetian speaking in those years

In 1814 the city was restored to Austria by the Congress of Vienna, but the Italian language remained the official language (with German). After that year some slavs started to settle in the city from the surrounding territories.

The Cattaro population in 1848 showed strong support toward Venice and the early Italian Risorgimento: