This month I am going to deal with the disappearance in Dalmatia of the authocthonous Italians of Spalato (a city called "Split" in Croatian language).

We all know that Spalato was a city developed inside & around the Diocletian roman palace, where the romance speaking inhabitants remained the majority of the population until the centuries of the Republic of Venice (if interested read in italian: https://www.proquest.com/docview/2566529651?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true). Let's remember that Spalato was one of the "Dalmatian City-States" (read my https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dalmatian_city-states), where the authocthonous Dalmatian romance language survived until the end of the early Middle Ages, when was started to be substituted by the venetian dialect (now called "Veneto da Mar").

Furthermore, it is noteworthy to pinpoint that in 1721 Venice controlled all Dalmatia west of the "Linea Mocenigo": please see the following map.

Map showing the "Linea Mocenigo" in 1721

But -since the Habsburg took control of the city in the early XIX century- the Italians of Spalato started to "disappear" (substituted by the Croatians) in a way that some scholars judge as an "ethnic cleansing" (please read in italian: https://www.studiober.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/06-La-politica-antiitaliana-nelle-amministrazioni-Jugoslave.pdf).

Indeed, the city of Spalato in the 1910 Habsburg census had 21,407 inhabitants; of these, 2,082 (9.73%) declared Italian as their language of use, but the percentage of those who declared they used Italian was 12.54% in the 1880 austrian census and was nearly 20% in the mid 1800s!

Furthermore, the 1816 Austro-Hungarian census registered 66,000 Italian speaking people between the 301,000 inhabitants of Dalmatia, or 22% of the total dalmatian population (while Spalato had nearly 10,000 inhabitants of which more than half were italian language & venetian dialect speaking, according to the linguist Matteo Bartoli). But in 2010 they were reduced in Dalmatia to only a few hundreds and in Spalato to just a few dozen.

It is noteworthy to remember that the Treaty of Rapallo stipulated by the Kingdom of Italy and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenians on 12 November 1920 fixed the border in such a way as to leave only Zara/Zadar under Italian sovereignty: in D'Annunzio's Fiume/Rijeka the response would have been a bloody Christmas, in Dalmatia annexed to the kingdom of the Karađeorđević there would have been the exodus of almost all the Italian communities of Sebenico/Šibenik, Spalato/Split and Trau/Trogir; so 3,000 refugees stopped in Zara, thousands more poured into the italian peninsula, concentrating in Rome and Trieste in particular.

This flow of nearly 20,000 exiles from Dalmatia was in continuity with the emigration of those Dalmatians who at the end of the nineteenth century suffered the discriminatory Austro-Hungarian policies which had favored the rise of the Croatian component, more loyalist than the Italians suspected of irredentism. Sebenico in 1873, Spalato in 1882 and in between many other municipal administrations have previously passed from the traditional Italian ruling class to the Croatian one; furthermore in 1905 Italian was banned from official documents and Zara remained the last cornerstone of Dalmatian Italianity. In the first two decades of the XX century, the attacks from croatian fanatics increased in a huge way, until the July 1920 murder of Italians in Spalato, that was the cause of the Trieste burning of the Narodni Dom (the "Balkan"). If interested for further detailed info, please read in italian:http://www.arcipelagoadriatico.it/storia/dalmazia/DALMAZIA.html.

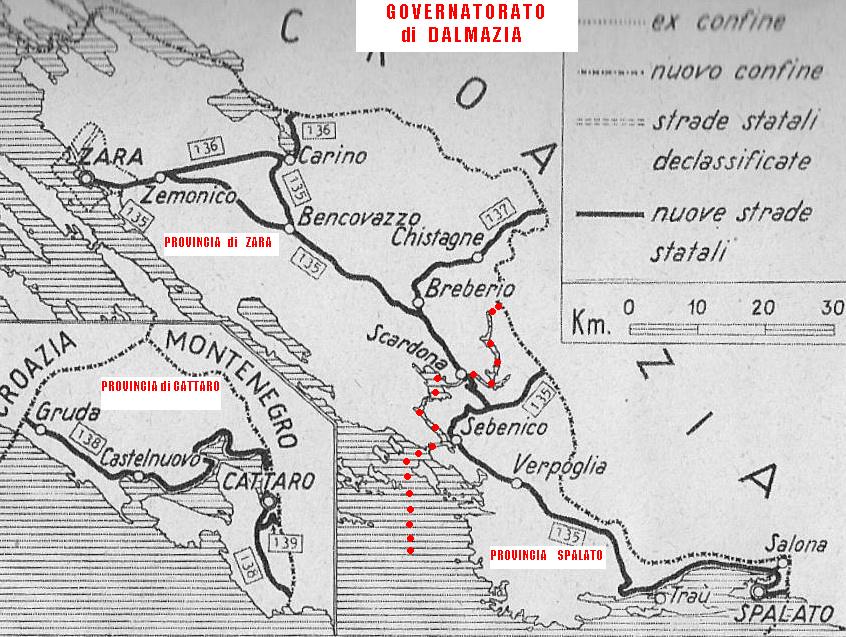

Only during the Second World War (read https://www.ilpostalista.it/pm_file/pm_122.htm) did Italy return to Dalmatia & Spalato, creating the "Governorate of Dalmatia" (see the following map) between 1941 and 1943, while Istria was Italian after the First World War for about thirty years (1918-1947) - even though it was actually Italian until September 1943 (or for 25 years).

Map of summer 1941 with the initial borders between the provinces of Zara/Zadar and that of Spalato/Split (which included Sebenico/Sibenik). Subsequently, the boundary between the two provinces was moved south of Sebenico to the border line established in the Treaty of London of 1915 between Italy and Yugoslavia.

Because I want to research in full detail this issue, I am going to translate excerpts from the famous book of Luciano Monzali "ANTONIO TACCONI E LA COMUNITÀ ITALIANA DI SPALATO" (https://www.academia.edu/10190651/Antonio_Tacconi_e_la_Comunit%C3%A0_italiana_di_Spalato):

CHAPTER 2: THE IRREDENTIST DREAM. ANTONIO TACCONI & THE NATIONAL STRUGGLES IN SPALATO FROM THE AUSTRIA-HUNGARY CRISIS TO THE WW1 AFTERWAR (IL SOGNO IRREDENTISTA. ANTONIO TACCONIE LE LOTTE NAZIONALI A SPALATO DALLA CRISI DELL’AUSTRIA-UNGHERIA AL PRIMO DOPOGUERRA)

Antonio Tacconi spent his youth and adolescence in Spalato, where he studied in primary school in the Croatian gymnasium: thanks to these studies he acquired a perfect knowledge of Croatian and Serbian. Tacconi was a leader of the "Autonomous Italian Party" in the last years of the Habsburg domination, and then became one of the animators of the "Italian National Fascio" of Spalato, the organization that fought for the annexation of Spalato to Italy after 1918. Appointed senator of the Kingdom of Italy in 1923, Tacconi was the political leader of the Italian community of Spalato between the two world wars, becoming Mayor of the city during the fascist occupation (1941-1943) when Spalato was the capital of the italian "Governorato di Dalmazia". Like most of his compatriots, he was forced to abandon Dalmatia after the Second World War, to move to Italy, where he died in 1962.

The Tacconis were fervent Catholics, and this was an element that strongly marked Antonio, throughout his life as a practicing religious person and in close relations with the ecclesiastical circles of Split. He grew up in a Spalato which was now politically dominated by the Croatian parties. But the domination of Croatian nationalism in Spalato, as we have seen, did not coincide for many years with a real and exclusive cultural and national hegemony: the presence of a strong Italian, mostly Italian, community in the old town, the use of the Venetian dialect by the Spalato population, the love of many Spalato Croatians and Dalmatian Slavs for the Italian culture meant that the social life of all "Spalatini" were strongly impregnated by the Italian language and culture. The last part of the nineteenth century and the first The twentieth century, however, were years during which the national struggles in Spalato worsened and began to dominate the political life of the city.

It is noteworthy to pinpoint that the pro-Serbian nationalist enthusiasm of the Croatian militants was the source of numerous incidents in Spalato. The radicalization of Croatian-Yugoslav nationalism in the years of the Balkan wars, especially among the new generations, caused a growing intolerance of the most extremist militants towards the survival of culture and of an Italian minority in Spalato. This intolerance manifested itself in numerous acts of hooliganism and intimidation towards shops with Italian writings and towards homes of autonomists and Italians. The children who attended the Italian school of the Italian National League were insulted and often attacked. Every public demonstration that had an Italian or autonomist character (from funerals to musical performances) was contested and disturbed by students and young Yugoslav with Croatian nationalist militants. Between the end of 1913 and the beginning of 1914 the campaign launched by extremist groups for the boycott of shops owned by citizens of the Italian Kingdom or of Italian nationality operating in Spalato and the incidents caused by the prohibition, decided by the Spalato municipal administration, for Italian autonomist musical groups and associations to participate in the traditional parade in honor of San Doimo, caused a great stir and created strong agitation among the Italian minority.

The outbreak of war between Italy and Austria-Hungary in 1915 resulted in the crisis of Spalato's autonomist associations. The Autonomous Italian Party (of which Tacconi was a member and manager), the National League and the Society of Italian Students of Dalmatia were dissolved, and all the Italian schools in Spalato were suppressed. All Italian associations ceased to operate and be active. Some Italian Spalatini fled to Italy making an explicit irredentist choice (like Francesco Rismondo).

Francesco Rismondo, a "Spalatino italiano" decorated with the Italian military gold medal in WW1

In the mythology of Italian Dalmatian irredentism, Francesco Rismondo, a young man from Spalato, who fled to Italy and enlisted in the Italian army, became famous.

Rismondo fell prisoner into the hands of the Habsburg army in the Carso battles and was executed by hanging at the end of 1915.

More generally, the entire political establishment of Spalato was hit hard by the outbreak of the Austro-Serbian and then Austro-Italian war.

After the collapse of Austria-Hungary in the autumn of 1918, Italy occupied with its troops the territories that had been promised to the Italian kingdom in the London Pact: in Dalmatia the cities of Zara/Zadar and Sebenico/Šibenik, their hinterland and the islands of Cherso/Cres, Lussino/Losinj, Veglia/Krk, Lesina/Hvar, Lissa/Vis and Curzola/Korcula. But in accordance with the provisions of the armistice between the Entente, the United States and Austria, Trau/Trogir, Spalato/Split and the rest of the Dalmatian coast were excluded from the Italian occupation zone. At the end of October 1918, in the Spalato region the collapse of the Habsburg state led to the formation of a provincial government led by a (croatian) committee composed of the (fanatic) Smodlaka and (double-face) Tartaglia, which proclaimed the union of Dalmatia with the Serbo-Croatian-Slovenian state.

Antonio Tacconi, Mayor of "Spalato italiana" (28 April 1941 – 8 September 1943)

In those weeks, the leaders of the Spalato's Italian Autonomous Party decided to create a new political organization, the "Italian National Fascio", led by a Committee in which Antonio Tacconi participated: the explicit objective of this National Fascio, a political organization that had nothing to do with Mussolini's subsequent Fascism, was to fight for the union of Spalato with Italy.

-----to be continued next month of November 2023....