During its short colonial history, Italy occupied several African territories such as Eritrea, Somalia, Ethiopia and Libya: rather vast and interesting dominions. It is lesser known, on the contrary, the story of another small and far colony in China: Tientsin (a town ca. 200 km south of Beijing) and the so-called commercial quarters of Shanghai and Beijing (under the direct sovereignty of Rome as from 1901, after the failed Boxers' revolt), two small Italian enclaves inside the Chinese state, which hosted Italians as well as larger English, French, Russian, German and Japanese territories since the end of XIX century. Additionally, there were also a few forts and commercial places under Italian control.

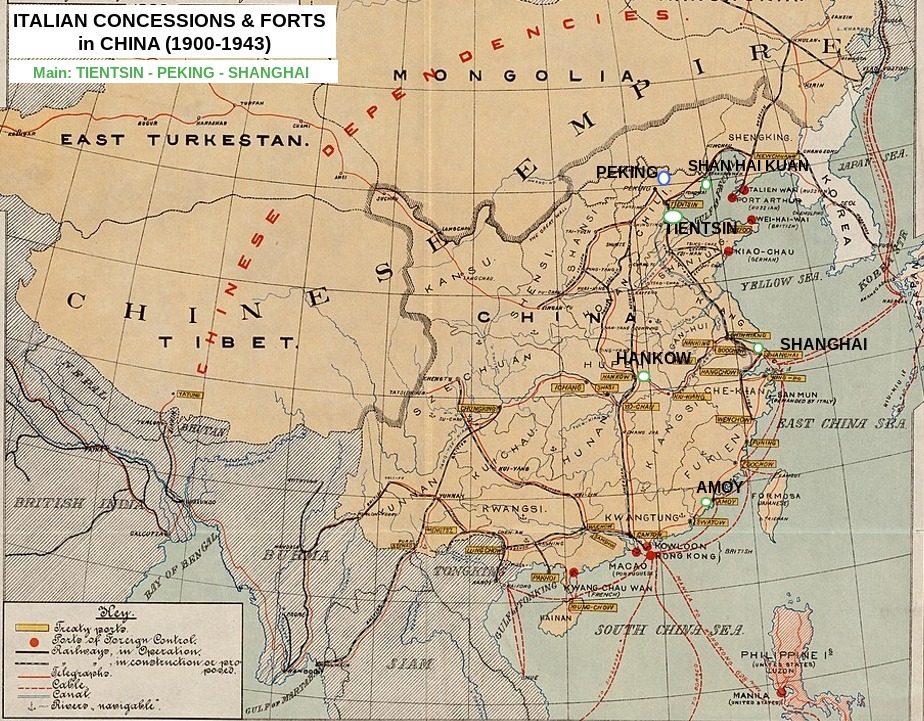

Map showing the Italian concessions & forts in China. Additionally there were (but together with other colonial powers): Taku (fort with Great Britain) and Beihai (port with only commerce rights). However Italy had full colonial controls only in the Tientsin concession

Seven locations & one treaty port

Italy in the first half of the 20th century has had concessions in Peking, Tientsin, Shanghai, Amoy and Hankow with two forts (Shan Hai Kuan and TaKu). However it is noteworhy to pinpoint that only in Tientsin, Peking and Shan Hai kuan, the italian government was in control (with colonial property rights). In the other locations Italy was united (or affiliated) with other colonial powers - like with Great Britain in the Taku forts.

There was even the Treaty Port in Beihai (southern China), that was allowed to have a small area for Italian commerce.

History

It all started with the "Boxer rebellion" and consequent war of the Boxers & China against the "eight powers"(Great Britain, France, Italy, Austria-Hungary, Germany, Russia, the United States and Japan).

THE BOXERS REBELLION:

On 20.4.1900, the so-called "war of the Boxers" began (the members of a secret society with a xenophobic orientation were so called). In Pao-Ti-Fung, in fact, a first bloody battle developed between gangs of insurgents and a community of missionaries and Chinese converts to Christianity (as such, considered bearers of Western culture). The clashes spread in a very short time and immediately the main powers sent their ships to Taku (port near Tien-Tsin) to land units of sailors. The command of the operations was assumed by the British Admiral Seymour. At that time only Elba and Calabria were found in Italy for Italy; both landed a group of 40 sailors (the former under the command of T.V. Paolini and the latter under the command of T.V. Sirianni) who together with other allied contingents headed, respectively, for Peking and Tien-Tsin to protect the existing Legations. After these moves the Allied strength at Peking reached 428 men and at Tien-Tsin 402 men. It was therefore a small force that could be reinforced with another 950 men or so who could be unloaded from ships already existing on site (without affecting their operational efficiency); of these, about 20 men could still be taken by Italian ships. Shortly after the situation worsened and Adm. Seymour then decided to land the rest of the available men as well; from the ship Elba therefore landed another 20 sailors who, under the command of the S.T.V. Carlotto, were sent to Tien-Tsin. In the meantime, the ships of the great powers continued to arrive at Taku with a relative influx of new contingents. Thus, on 10.6.1900, Adm. Seymour decided to resign marching towards Beijing in command of a column of 1782 men which also included 20 Italians. A few days later (June 17), an allied force made up of 5 gunboats of Russian, German and French nationality (on which a group of 24 Italian sailors under the command of the S.T.V. Tanca had also been embarked) instead conquered the forts of Taku in order to ensure the free connection between allied ships and troops on land. In response to the loss of Taku's forts, the Boxers, who already occupied the walled city of the Chinese quarter of Tien-Tsin, attacked the Legations located on the European side of the city and it was therefore in this phase that the death of S.T.V. Carlotto (this was the first of our fallen in the Boxer War; later, for various causes, another 64 Italian soldiers died). Thus we arrived at 26 June when Adm. Seymour, unable to reach Beijing due to the great numerical superiority of the insurgents and the continuous clashes with the latter (in which five of our sailors died), made his return to Tien-Tsin (where in the meantime the city had also fallen into the hands of the allies Chinese wall). At the same time, the news arriving from Beijing was increasingly dramatic. On the allied side (in the meantime reinforced by the arrival of new contingents of infantry) it was therefore decided to intervene by sending an expeditionary corps from Tien-Tsin. To this end, a contingent of land and sea troops was set up, armed with 70 cannons, divided into two columns: one by Japanese, English and Americans (about 12,700 men) who had to follow the right side of the Pei-ho river and the other by Russians, French, Germans and Italians (about 5,000 men, among which the Italians were 35) who had to follow the left side of the river. These men set out on August 4th. Meanwhile in Beijing the Legation Quarter had been subjected to a massive siege with continuous bombings by the Chinese; on June 21st the Belgian and Austrian legations went up in flames and on the 22nd it was also the turn of the Italian one. The fighting between a few defenders of various nationalities and the hordes of insurgents who launched themselves in waves to attack the defense lines of the Legation quarter succeeded each other more and more bloody throughout the month of July and in the first two weeks of August until, on 14 August , the contingent departed from Tien-Tsin arrived at contact with the enemy by subjecting him to shelling. It was the column made up of Japanese, English and Americans as the one made up of Russians, Germans, French and Italians had been forced to return to Tien-Tsin after only two days of march being essentially made up of sailors with little training in the long run marches; this second column was in any case immediately replaced by another made up of infantry elements (which in any case also included the Italian sailors under the command of Ten. Sirianni) which arrived in Beijing when the liberation was now complete. In a few hours the troops allies breached the city walls arriving near the imperial palace and forcing the Empress to flee (15.8.1900); thus ended the siege of Beijing, which lasted 55 days. In that famous event, the losses of the allies were 63 dead, of which 13 were Italians.However, the conquest of Beijing was now a fait accompli and therefore the use of the new arrivals, not only Italians but also of other nationalities), was destined for other areas that had until then remained at the mercy of the insurgents, from where news of massacres of missionaries and local Christians. Although often in uncoordinated formations, the various contingents began a series of operations to restore order and normality in places still marked by turbulence. The main operations in which the Italian units were engaged were: - from 9 to 12 September : an expedition to Tu-Liu. From this location, it was feared that a Boxer attack on Tien-Tsin might be launched. Of our expeditionary corps, 350 bersaglieri and 600 men of infantry took part. - From 19 to 21 September: the occupation of the forts of Pei-Tang. Around 1,000 Italians took part together with the allies. - From 29 September to 2 October: occupation of the forts of Chan-ai-Kouan. For Italy, 330 Bersaglieri and 140 sailors.-October 12 to 19: occupation of Pao-ting-fu. The operation was conducted by forming two columns of international troops: the one coming from Tien-Tsin included 358 Italians while the one leaving Beijing included 516 Italians.-3/ November 4: Cu-nan-shien is occupied. The action was conducted under the command of Col. Garioni and around 170 Italians took part. - From 12 to 26 November: expedition to Kalgan. 599 Italians took part in the occupation of the city and other neighboring localities. Thus we arrived in the middle of winter, with temperatures that often reached 10 degrees below zero. Nonetheless, our troops took part in numerous expeditions whose purpose was to quell in the bud the outbreaks of tension or to punish small armed bands operating in the area. The main actions of this kind were carried out at Er-lan-ciuan; Tung-Hi; Ma-fang-tshwange Ping-Ku-shien. After these operations the situation moved towards normality. The peace definitive text was signed in Peking on 09.07.1901. The Boxer War was therefore officially over.

Photo of some soldiers of the "Eight powers" (from left: Britain, United States, Australia, India, Germany, France, Austria-Hungary, Italy, Japan. Australia and India were under Britain control), but without Russia

The history and the vicissitudes of those eastern settlements, which remained under the Italian dominion for nearly half a century, involved not only the diplomatic representatives and the few Italian colonists but also the forces of the Army and the Navy. The larger part of about Italian 20,000 soldiers and officers who fought in the victorious campaign (June-August 1900) against the Boxers' rebel Chinese nationalists troops - allied to the United States, Great Britain, France, Austria-Hungary, Germany, Russia and Japan - were recalled from Beijing after the end of the conflict. One year later, the signing of the peace treaty between Empress Tsu Hsi and the colonial powers (7th September 1901) made Italy the right to occupy a portion (nearly one square kilometre wide) of Tientsin and two commercial quarters in Beijing and Shanghai (it was temporarily enlarged in 1927 with the addition of the former Austro-Hungarian concession)

The Savoy government decided to implement the growth of missions, communities and commercial companies in those new settlements by sending diplomatic attachés and one special military force in charge of the protection of those tricolour territories. In 1915, when Italy entered the war alongside the Central Powers, the colony of Tientsin counted about 10,000 inhabitants (Chinese) and 350 to 400 Italians, most of whom were traders. At that time the defence of the settlement was entrusted to only ca. 200 soldiers and officers (mostly Bersaglieri) supported by a special battalion (composed by Austro-Hungarian POWs of Italian origin captured in Galizien by the Imperial Russian troops and then released and transferred by train to Far East to reinforce the Italian garrison in China) and by some fifty Chinese militiamen. A few years later, when the war ended, the government of Rome finally decided to strengthen the garrison with a well-armed and trained intervention force. On 5th March 1925 the Battaglione Italiano in Cina was ready to be shipped to China. It was a very skilled unit, mostly composed of soldiers of the elite Reggimento San Marco. The battalion was quartered in the new barracks named Ermanno Carlotto and consisted of three companies of 100 men each: the San Marco Company, the Libia Company and the San Giorgio Company

On 18th April 1928, the San Marco Company was inspected by the former Chinese emperor Pu-Yi during his visit in the Italian settlement. At the beginning of 30s, the Italian colony began to steady, also thanks to the good diplomatic relationship set between Rome and Beijing and also to the improvement of the trading and technical exchange set up between the two countries (the Chinese government even entitled two Italians, Gibello Socco and Evaristo Caretti, respectively for the direction of the Ministry of Railways and the Ministry of Post). Tientsin as well as the Italian quarters of Shanghai and Beijing had quite a serene period during the first half of 1930s, characterised by a fairly good commercial town planning and entrepreneurial growth. With the arrival of Mussolini's son-in-law Galeazzo Ciano appointed secretary at the Beijing's legation and then minister plenipotentiary in Shanghai this process further improved, together with the relationship between Rome and the new Chinese leader Chiang Kai Shek. In particular, Ciano became close friend with a leading exponent of the Chinese nationalist's military elite, especially with Marshall Chang Hsueh Luang a true admirer of the Mussolini's fascist regime. In 1932, soon after the Mukden's accident (the first act of Japan's clear hostility against China) to prove once more the friendship towards Italy Chiang Kai Shek choose Ciano as a go-between with the Japanese representative. In 1932 - under Ciano's pressures for creating an even stronger economic and military alliance between China and Italy the Italian shipping company Lloyd Triestino opened a new service linking Italy to Shanghai by scheduling on that route two modern transatlantic vessels, the Conte Biancamano and the Conte Rosso (which immediately settled a speed world record of only 23 days during the first voyage). With this new service, supported by those ones of other companies employed in the trade of various goods and products, the economic exchange between Italy and China reached such good levels to alert Great Britain and France

It was in that period that Italy started to provide Beijing with military aircraft. After he presented Chiang Kai Shek with a three-engined Savoia Marchetti, Mussolini sent to China a huge delegation of pilots, engineers, technicians and trainers to convince the Nanking's government and the young Chinese aviation's representatives to purchase Italian military airplanes and to accept the survey for the creation of factories to build on purpose licensed models offered by Rome. The Italian aeronautical delegation , commanded by General Roberto Lordi and composed by renown aces and test pilots such as Valentino Cus and Mario Bernardi (become famous thanks to his speed record of 700 km/h set by his special Macchi hydroplane) did not succeed in its goal. The Chinese government decided in fact to purchase only a small number of Fiat CR32 and some bomber-reconnoitres Caproni Ca101, Ca111 and Ca133. On 6th November 1937 when Italy joined the Anticomintern Pact - the relationship between the two countries suddenly changed. Mussolini, by signing that agreement, got close to Tokyo, opening a series of good exchanges with powerful Japan, which in the meantime had become the worst enemy of weak Nationalist China. It goes without saying that Chiang Kai Shek did not like at all this decision and broke off any relationship with Rome.

Magazine image of the Italian troops ("Bersaglieri") conquering a fort in China in 1900

The new situation caused the immediate isolation to the Italian colony of Tientsin and the quarters of Shanghai and Beijing, which felt immediately hostility from all around. The military responsible of the colony and the Partito Nazionale Fascista's representatives (at that time in China the party's secretary was Carlo Fumagalli) realised soon the dangerous situation, considering the insufficient Italian forces set to defend the garrison. They immediately demand from Rome for an urgent supply of men and warships. This request even if it was dealt with a small quantity was fulfilled in quite a short time, but unfortunately not before the war between China and Japan broke out. Some months before, in July 1937 - when the first fights had started between Japanese and Chinese troops - Commander Bacigalupi of the gunboat Lepanto had got in charge of the first Italian defence detachment, composed by part of the Ermanno Carlotto's and Lepanto's crews. The Tientsin based Battaglione Italiano in Cina joined soon to these forces. A few months later when the well-trained and combat hardened Japanese armies had spread out the Chinese territory - the Italian Comando Supremo decided to send more forces (some hundreds of soldiers) and the light cruiser Raimondo Montecuccoli to Tientsin. This cruiser sailed from Napoli on August 27th and arrived to Shanghai on September 15th, just to coincide with the first Japanese air bombings on the town. By then, at least what with 1,200 Army's and Navy's soldiers were in China to defend the safety and the interests of its 500 to 600 resident compatriots.

On the whole, in 1937, in Tientsin and Shanghai there were stationed 764 men with officers and soldiers of Battaglione Granatieri di Sardegna arrived by ships from Massaua (Eritrea). Part of these effectives supported the English (2,500 men) and the American (1,400 men) contingents who were already in Beijing and particularly in Shanghai to protect the Anglo-Saxon citizens (in Shanghai there were 308 American civilians, 971 English, 199 Germans, 654 Japanese, 182 Russians and 42 Italians). On September 27th and October 24th, some Japanese bombers Mitsubishi attacked the Italian light cruiser Montecuccoli during a raid against Shanghai. During these two missions was the Italian vessel hit by splinters and had one dead and several injured (the accident compromised seriously the diplomatic relationship between Rome and Tokyo).

Foreign Troops (1933) in Shanghai : British Forces: 2,160; French Forces: 1,982; Japanese Forces: 1,934; U.S. Forces: 1,758; Italian Forces: 108 (https://www.worldstatesmen.org/China_Foreign_colonies.html)

On August 6th 1937, the Italian Comando Supremo decided to move 30 soldiers stationed in Shanghai and Hankow to protect the local Italian consulate. This small group was transferred to its destination from the Montecuccoli, which definitely left China for Italy on August 29th. On December 23rd the cruiser was replaced by its sister vessel, the light cruiser Bartolomeo Colleoni, which stood in defense of the Italian garrisons in China until 5th September 1939, when it was called back to Italy due to the Second Conflict's outbreak. In the same year, part of the contingent (composed also by effectives of Air Force, Carabinieri and Guardia di Finanza (i.e. Revenue Guard Corps)) was repatriated, leaving to the garrison part of the weaponry and two small naval units (the gunboats Lepanto and Carlotto in Shanghai and Tientsin).

After the Italian declaration of war (10th June 1940), the Navy's Comando Supremo ordered to some Massaua-based units to sail to Far East. This decision was made due well-grounded fear that in case of fall of the East Africa Empire, the English could have had the chance to get hold of the Italian ships. Thus, in February 1941 (less than two months before the British capture of the Massaua's base) the colonial ship Eritrea (armed with four 120 mm, two 40 mm guns and two 13.2 mm machine guns) and two armed vessels (Ramb1 and Ramb2: two modern and fast banana-carriers converted into auxiliary cruisers by the equipment of four 120 mm guns and some anti-aircraft 13.2 mm machine guns) sailed to Kobe (Japan) and, in alternative, the ports of Shanghai and Tientsin. While the Eritrea and the Ramb2 reached their destination, avoiding the patrolling of the Royal Navy, the Ramb1 met off the Maldives Islands with the New Zealand light cruiser Leander, by which it was sunk.

Between March 1941 and September 1943 the Italian concession of Tientsin and the consulates of Shanghai, Hankow and Beijing lived a quite peaceful period, in spite of the not optimal relationships with the Japanese occupation military Command. This last one, in fact, did not like the presence of Europeans - even if Japanese allieds like the Italians - in the government of towns or even quarters located in their zone of influence. Notwithstanding this, the Italian military attaches and diplomats in China and Japan tried to lower as much as possible the reasons of friction, even when Tokyo forbade to Eritrea and Ramb2 to carry out offensive cruises against the English fleet in the Pacific Ocean (the Japanese, at least until 7th December 1941 - date of the unexpected attack to Pearl Harbor - did their utmost in order to avoid whichever embarrassing situation with USA and Great Britain). Only after Japan's official entering in war, Eritrea was allowed to lend support to the Italian oceanic submarines reaching Penang and Singapore from the far base of Bordeaux, loaded with strategic products and goods destined to the Japanese industry of war. Concerning the many Italian cargo ships which were within Chinese and Japanese water when Italy entered the war allied to Germany against Great Britain and France, most of them (such as the large steamer Conte Verde) remained unemployed or had to perform voyages for the Japanese, while some others tried to reach the French coast (Bordeaux), by breaking the British blockage. Some of these latter succeeded in their goal, carrying to Europe quite good quantities of strategic cargoes (rubber, quinine, tin).

Very interesting

ReplyDelete