Romans created colonies for their veterans in the territories they conquered. Four were created in the British isles. The following essay is a brief research on one of these colonies in Roman Britannia: Camulodunum (actual Colchester).

The 1st century colonies at Camulodunum/Colchester (Colonia Claudia Victricensis), Lindum/Lincoln (Colonia Domitiana Lindensium), and Glevum/Gloucester (Colonia Nervia Glevensium) were founded as settlements for legionary veterans. The creation of three coloniae on the sites of earlier fortresses was a useful expedient whereby time-served legionaries could be discharged, form a military reserve, and receive their due grant of land with minimal disturbance of the native population.

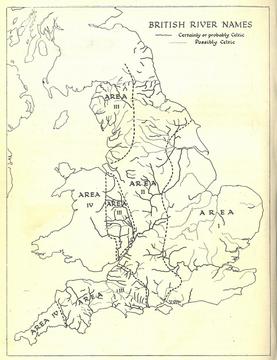

Map showing the four colonies of veterans in Roman Britannia and the area Romanized & populated by the Romano-Britons around these colonies in 410 AD. Note that the 3 original colonies enclosed a perfect equilateral triangle, later expanded to the north with the creation of the veterans' colony of Eburacum by emperor Septimius Severus (when he tried the full conquest of Caledonia/Scotland in the third century)

In contrast, the sites of the fortresses at Exeter (Isca Dumnoniorum) and Wroxeter (Viroconium Cornoviorum) became tribal centers of the local Britons.

The only other known Roman colonia in Britain, at Eboracum (York), is generally believed to have been promoted to this status in the early 3rd century.

It is noteworthy to remember that Tacitus wrote that in winter 84 AD all Britannia was fully conquered by the Romans: even all Caledonia/Scotland.

He wrote that under Agricola "Britannia perdomita est" (Britain is fully dominated), where the word 'perdomita' in latin is a reduction of the words "PERfecta DOMInaTA" (in English: totally conquered/dominated). Of course Agricola -after his victory against the Picts (called "Caledonians" by the Romans) at the battle of Mons Graupius in the fall of 84 AD- in spring 85 AD was ordered to leave Britannia and went back to Rome, so he could not consolidate his full control of all the huge island of Britain. Romans soon dismantled also the huge Inchtuthil fort in the 'Gask Ridge' and went south of what is now the 'Antonine Wall', losing control of Caledonia after only a few winter months of full rule.

But in the southern half of Britannia they ruled the country for many centuries and settled there many thousands of their veterans. Furthermore, the genetic signature of the haplogroup "R1b-U152" (ancient Romans, from the original founders of Rome to the patricians of the Roman Republic, were essentially R1b-U152 people) is found at low frequency almost everywhere in the British Isles, but it is considerably more common in eastern and southern England (5-10%), reaching a peak of more than 15% in East Anglia and Essex (around Camulodunum and St. Alban) and in Kent.

In Roman Britannia the majority of administrators, land owners and legionaries (at least in the first century of Romanization) would have hailed from Italy: it is possible that approximately one third of the autosomal genes in the actual British population comes from Mediterranean people (mostly Italians, but also Iberians, Greeks, Anatolians and a few Egyptians, Berbers, Phoenicians, etc...), who settled in Britain during the Roman period (read for further information:https://www.eupedia.com/genetics/britain_ireland_dna.shtml#romans).

Indeed the area of the British isles within (and "protected" by) these four colonies was the most Romanized of ancient Britannia (read for additional information: https://suscholar.southwestern.edu/bitstream/handle/11214/227/Broyles.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y).

It is noteworthy to pinpoint that these four cities were the few Roman settlements in Britain designated as a 'Colonia' rather than a 'Municipia', meaning that in legal terms it was an extension of the city of Rome, not a provincial town. Its inhabitants therefore had full "Roman citizenship" with all the related rights.

In the third century in Roman Britannia there were nearly 4 million inhabitants, enjoying an era of prosperity that the same Winston Churchill admired (in his famous "A History of the English-Speaking Peoples"). But after the plague of the Antonine period, plus other negative circumstances (like the withdrawal of all the Roman military) in the mid fifth century there were only half of them: less than 2 millions. Even if it looks very strange, they were dominated by 200,000 Anglo-Saxons in a few decades after the Romans left the British isles. Some scholars think that the reason (probably together with the plague of 450 AD) was that only the cities were fully Romanized, but less than 20 percent of the Britannia population lived there, while the peasant/farm areas (where most people lived) were only minimally Romanized and did not know how to defend themselves from the strong & well organized German invaders in the fifth century.

However the Romano Britons were able to stop for some decades the Anglosaxon conquests, with their legendary Badon hill victory around 500 AD (under the leadership of the Romano-Briton Ambrosius Aurelianus, who was identified by the scholar J. Morris as -perhaps- the legendary King Arthur). This happened in the same years when the last fully Roman emperor -Justinianus- did the tentative to reconquer all the western roman empire, that has previously fallen in the barbarian control (and the Romano Britons probably received some help & military advice from him).

Additionally we must remember that the Plague of Justinian (that killed as many as 100 million people across the world: as a result, Europe's population fell by around 50% between 540 and 600 AD !) entered the Mediterranean world in the 6th century and first arrived in the British Isles in 544 or 545 AD. Just before the battle of Dyrham in 577 AD, that was the beginning of the final conquest of Subroman Britannia by the Anglosaxons: the important Romano-britons city of Calleva was abandoned in those years, because hard hit by this terrible plague.

Richard Lehman wrote that "....in 550 AD, the island of Britain was predominantly Romano-British: they were unable to maintain a full urban civilisation after the departure of the Romans in 410 AD, but were successful at keeping the Angles and Saxons confined to Anglia and Kent (after the battle of Badon Hill). There was no trade or social exchange between the Christian British and the pagan Angles and Saxons, once they had had fought each other to a standstill under King Arthur. The British carried on some trade with the Mediterranean, whereas the English lived on what they could grow. So when the plague reached Britain in boats from mainland Europe, it killed up to half of the native Romano-British population but left the English colonists largely unscathed. Not long afterwards, the English began to mount probing raids into British territory and found that there was little opposition. They sent word back to their relatives in Schleswig-Holstein and the Danish peninsula that the whole island was up for grabs. The king of the Angles was so impressed that he put his entire population into boats and left the area west of Hamburg deserted for several centuries. And so, 150 years after Hengest and Horsa first brought in Saxon warriors to police the borders of crumbling Roman Britain, the English decisively colonised plague-ravaged Britain from the borders of Wales to the middle of Scotland...…"

Map of southern Sub Roman Britain in 575 AD, just before the "Battle of Dyrham", showing the areas of Romano-Britons, Saxon & Jute settlements according to the historical sources (Bede)

Furthermore, scholars such as Christopher Snyder (read http://www.the-orb.arlima.net/encyclop/early/origins/rom_celt/romessay.html) believe that during the 5th and 6th centuries – approximately from 410 AD when Roman legions withdrew, to 597 AD when St. Augustine of Canterbury arrived – southern Britain preserved a sub-Roman society that was able to survive -for a while- the attacks from the Anglo-Saxons and even use a vernacular Latin (called "British Latin") for an active culture. There is even the possibility that this vernacular Latin lasted to the late 7th century in the area of Chester and Gloucester, where amphorae and archaeological remnants of a local Romano-British culture (mainly in the locality called 'Deva Victrix') have been found.

Indeed -according to H. R. Loyn (in his "Anglo-Saxon England and the Norman Conquest". Harlow: Longman; p. iii; 1962)- as late as the eighth century the Saxon inhabitants of St. Albans (an important city nearly 70 km west of Camulodunum) were aware of their ancient neighbors of the Roman city called 'Verulamium', which they knew as "Verulamacæstir" (the fortress of "Verulama"), possibly a pocket of Romano-British speakers remaining separate in an increasingly Saxonised area.

Scholars have seen signs of continuity between many "late" Roman towns and their medieval successors. Urban continuity has been confirmed for Bath, Canterbury, Chester, Chichester, Cirencester, Exeter, Gloucester, Lincoln, London, Winchester, Worcester, and York. At Verulamium (St. Albans), where the medieval town grew up around the Saxon abbey outside of the Roman walls, archaeologists found several late fifth-century structures and a newly-laid waterpipe indicating that a nearby Roman aqueduct was still providing for the town's sub-Roman inhabitants in the sixth century. At Silchester, which did not become a medieval town, excavations revealed that economic activity at the forum continued into the fifth century (dated by coins and imported pottery and glass), while jewelry and an ogam inscribed stone hint to late sixth century contacts with Irish settlers (read for further information: http://www.vortigernstudies.org.uk/artgue/snyder.htm).

Indeed the British economy did not collapse during the early Sub Roman period. Although no new coinage was issued in Britain, coins stayed in circulation for at least a century (though they were ultimately debased); at the same time, barter became more common, and a mixture of the two characterized 5th (and early 6th) century trade. Tin mining appears to have continued through the post-Roman era, possibly with little or no interruption. Salt production also continued for some time, as did metal-working, leather-working, weaving, and the production of jewelry. Luxury goods were even imported from the continent -- an activity that actually increased in the late fifth century. Only after the mid sixth century started a deep crisis for the Roman Britons: this fact coincided with the decades of the terrible "Constantine plague" (that reached Britain around 545 AD).

CAMULODUNUM/COLCHESTER

Balkerne Gate, a 1st-century Roman gateway in Camulodunum, it is the largest surviving gateway of Roman Britain

The foundation of this Roman colony of veterans -at the English site named 'Colchester' today- took place in AD 49. The actual name is derived from the Latin words 'Colonia' and 'Castra' (chester in ancient Brythonic). The Roman town began life as a Roman Legionary base constructed in the AD 40s on the site of the Brythonic-Celtic fortress (called 'Camulodunum' by the Romans) following its conquest by the Emperor Claudius. After the early town was destroyed during the Iceni rebellion in 60/1 AD, it was rebuilt: it reached its zenith in the 2nd and 3rd centuries, when the city had a population of more than 30,000 inhabitants (some historians argue that could have had nearly 50,000 citizens, including the many "villas" in the surrounding areas). During this time it was known by its official name "Colonia Claudia Victricensis" (usually called "COLONIA VICTRICENSIS) and as 'Camulodunum', a Latinised version of its original Brythonic name.

Tacitus tells us that it had a dual purpose: as a military base in the hinterland of the frontier zone, and as a model of Roman urban life (Tacitus Ann., 12.32). This statement has some support from archaeological excavations: some military barracks were not demolished but continued to be used in modified form in the early colonia, while at the same time public buildings were being erected and a new street system laid out to the east of the fortress site.

On the other hand, the early colony had no defences: after the events of AD 61 (when the Britons revolted under queen Boudicca), this mistake was not repeated. Evidence has been found near the Balkerne Gate, the later west gate of the town, for a defensive system built soon after the Boudican revolt, consisting of a ditch and presumably also an earth bank. This line was abandoned around 75 AD when the defended area was apparently extended westwards, the former western boundary being marked by a monumental arch. This arch was incorporated into the new Balkerne Gate when the city wall was built along the line of the earliest western defences in the early 2nd century (if interested in some nice maps of Roman Britain showing also Camulodunum, please go to https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archives/view/romangl/map.html.

The main building of the city was the "Temple of Claudius", which dominated the landscape and was a lavish building decorated with marbles and porphyry imported from various parts of the Mediterranean world. Today the remains of the Temple forms the base of the 'Norman Colchester Castle': it was one of at least eight Roman-era pagan temples in Colchester (read https://web.archive.org/web/20140603222036/http://www.roman-britain.org/places/colchester_temples.htm) and was the largest temple of its kind in Roman Britain; its current remains potentially represent the earliest existing Roman stonework in Great Britain. On the west side of the colony a monumental gate of two arches, part of which survives as the actual 'Balkerne gate', was erected on the site of the Porta Decumanus. There is some uncertainty about the date of the arch, but it was probably erected c. 50 A.D. to commemorate the foundation of the colony.

Colchester also housed two of the five Roman theaters unearthed in Britain, one of which, located in Gosbecks (site of the home of a tribal chief of the Iron Age) was in the first century the largest in Roman Britannia, as capable of accommodating up to 5000 spectators. Furthermore it is noteworthy to pinpoint that in 2004, the 'Colchester Archaeological Trust' discovered the remains of a Roman Circus (chariot race track) underneath the Garrison area in Colchester, a unique find in Great Britain.

Some fine stretches of the Wall at Colchester survive, although in places the front was refaced in the medieval period. Built of alternate layers of "septaria" and mortar, with tile courses in both inner and outer faces, it was about 3 m wide at its base and slightly narrower above. Several interval towers have been found, all presumably contemporary with the wall.

Apart from the blocking and refacing of the 'Balkerne Gate' (sub roman/late Saxon-early Norman?), there are only slight traces of this rebuilding before the late medieval refacing. The dating evidence shows that the Wall was built between AD 100 and AD 150.

The 3 m wide wall of Colchester could easily have accommodated a wall-walk, although wide free-standing walls were most unusual in Britain before the late 3rd century. Their erection at Colchester at such an early date in comparison with other British towns must surely have been connected with the city’s colonial status.

The period between the mid 2nd and the early 3rd century saw in Roman Colchester, as in other towns of Roman Britannia, the appearance of substantial, well built town houses. Areas which had been used for cultivation were built over in response to the need for new building land within the walls. The houses themselves were often larger and of better quality than earlier ones, the courtyard house making its first appearance. Rubble foundations became the norm, especially for internal walls, and floors were frequently tessellated. Clearest testimony to the increase in affluence is the widespread introduction of mosaic pavements. Over 30 mosaics have been recorded in the town and, as far as can be judged, the overwhelming majority are of the period 150-250 AD.

Roman Walls of Camulodunum in modern Colchester

The pottery industry in particular was important to the local economy.

It was active from the Claudio-Neronian period to at least the late 3rd or early 4th century.

It was at its most successful from c. 140 to c. 230 AD, when large quantities of pottery were being exported to other parts of the country, especially to forts on the northern frontier.

For detailed information, please read data and see maps on the link: https://englaid.wordpress.com/2015/01/09/mapping-pottery/

Coins may have been struck in Colchester in the late 3rd century and the first half of the fourth century, when the city and the surrounding territory was fully Romanized (according to academics like John Morris). The 4th century did see an increase in the bone-working industry for making furniture and jewelry. And evidence of blown-glass making has also been found in Camulodunum.

Christianity was very important in the fourth century. During this period a late Roman church just outside the town Walls was built with its associated cemetery containing over 650 graves (some containing fragments of Chinese silk), and may be one of the earliest churches in Britain.

Additionally the huge Temple of Claudius, which underwent large-scale structural additions in the 4th century, may also have been repurposed as a Christian church, as a 'Chi Rho' symbol carved on a piece of Roman pottery was found in the vicinity.

With the withdrawal of the last Roman troops in 410 AD, the city -probably reduced to less than 5,000 inhabitants- started to suffer the attacks from the Saxons. A skeleton of a young woman found stretched out on a Roman mosaic floor at Beryfield, within the SE corner of the walled town, was interpreted as a victim of a Saxon attack on the Sub-Roman town in the first decades of the fifth century.

The fate of the Romano-British population of Colchester is unclear but life in the town was certainly radically different by the mid 5th century, the date of the earliest known Saxon presence in the city's area. It is uncertain whether elements of the Romano-British population survived the transition. Some houses were left standing and partially unoccupied, so that topsoil and broken roof accumulated on their floors. But some evidences suggest that some Romanized Britons (mixed with a majority of Saxon settlers) remained living inside the walls until the first decades of the sixth century.

Famous archaeologist Mortimer Wheeler pinpointed that the lack of Saxon archaeological remains in a triangle area between London, Colchester and St Albans could mean that there was a region "post-roman" were the Romanized Britons remained -for some decades- independent (surviving the Saxon invasions of southern Britain in the fifth century). One legend from the early 500s AD tells of a king by the name of Arthur, a Romanized Celt, who had a series of victories against the invading Anglo-Saxons. King Arthur's legend would grow during the Middle Ages, but his few victories were not enough to keep out the invaders.

Indeed historian John Morris in his masterpiece "The Age of Arthur" (1973) wrote that the Romanized Britons used to remember the prosperous centuries of Roman rule with nostalgia and so he suggested that the name "Camelot" of Arthurian legend may have referred to the first capital of Roman Britannia (Camulodunum) in Roman times.

Map showing Camulodunum in the King Arthur years.

Some historians (like John Morris) wrote that the 'Battle of Badon Hill', the famous victory of King Arthur and his Romano-Britons against the Anglo-Saxons (that blocked their advance & conquest of Britannia for nearly half a century), was probably fought in the proximity of Camulodunum around the year 500 AD

---------------------------------------------------------------------

I want to add to the above essay -written by B. D'Ambrosio of the University of Genova- the following excerpts of researches done by Peter Kessler and others, related to Camulodunum and other Roman cities during the sub-roman decades (from https://www.historyfiles.co.uk/FeaturesBritain/BritishSouthernBritain03.htm):

In most of the towns of Roman Britain, the usual civic life continued well into the fifth century after the legions' departure in 410 AD. Conscious attempts to live a form of Roman life persisted around early Christian churches such as those at St Albans, Lincoln, and Cornhill in London. Elsewhere, the populations of some Roman towns, such as Wroxeter and York, re-used old civic buildings for a more domestic purpose. The old bathing complex at Wroxeter was now the site of a large, timber town house surrounded by shops in a late Roman style. However there it is no doubt that the sub-Roman period was one of violent unrest. Hill-forts such as South Cadbury were re-occupied by Romano-British inhabitants, who strengthened their walls, presumably against some threat from invaders.

Indeed there are a series of regions, or territories, in the British south-east that get the most fleeting of mentions in various sources, with tantalising glimpses given of some of the possible Romano-Britons kingdoms that existed there in the short gap between post-Roman administration and Anglo-Saxon domination.

Brief mentions in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles give a vague picture of how the war was going, and centres of British resistance can often be deduced from the location of these battles, and from archaeological evidence.

Caer Celemion (Calleva)

Roman Calleva Atrebatum, the walled capital of one of the major southern Romano-British tribal cantons, could have survived as a possible Caer Celemion (modern Silchester) along with its southern neighbour, Caer Gwinntguic (Winchester). Evidence shows that Britons continued to command the territorium (formed roughly of Berkshire, and northern Hampshire and Wiltshire) into the seventh century, probably as a post-Roman continuation of the Celtic Atrebates. Local place names such as Andover, Micheldover and Candover are British-origin names.

This, together with an absence of early Saxon relics near Caer Celemion and a considerable number of male burials intrusive in prehistoric round barrows all along the nearby chalk country suggest casualties incurred in military operations and an unexpectedly vigorous persistence of sub-Roman authority in the region. There are also legends of a King Einion based around here.

Findings along the south of the Thames Valley (Caer Celemion's northern border) show that there were Saxons there from the early fifth century, in settlements at Reading, and further upriver at Abingdon, Dorchester and Long Wittenham. Saxon cemeteries and artefacts mix in with Roman material, suggesting these areas may initially have been settled by laeti to defend Caer Celemion's borders.

The Saxon settlements at Cassington and Brighthampton on the north side of the Thames above Oxford could well have started in a similar fashion (perhaps by neighbouring Cynwidion). However, when the encroaching Thames Valley Saxons reached them by around the 470s, the settlements became hostile territory for the British.

These laeti could have been supplied with sub-Roman metalwork from Calleva itself. It appears that in its final phase the basilica in the town centre was turned into a substantial metal-working area (Guide to the Silchester Excavations, M Fulford, 1982).

Another site which has produced very late Roman material is Lowbury Hill on the Berkshire Ridgeway overlooking the upper Thames basin (Caer Celemion's northeastern border). This apparently started as a pagan temple in late Roman times, but its final purpose was probably to serve as a look-out point related to the territory's outer boundary defences.

Further west, the fifth or perhaps sixth century construction of the Wansdyke was a massive undertaking which reached from west of Caer Baddan's capital (Roman Aquae Sulis, modern Bath) to the proposed northwestern corner of Caer Celemion's border.

The continuing vitality of sub-Roman Calleva during the fifth, and perhaps far into the sixth, century can be illustrated, not only by its substantial output of paramilitary metalwork and its probable maintenance of a defensible river frontier in the Thames Valley, where in the fifth century the main threat was from the Thames Valley Saxons.

It was also apparently protected by stretches of earthworks related to the Roman roads that led to it from the north and west. The existence of those in the north is unsurprising due to the obviously hostile relations between the sub-Roman Atrebates and the Thames Valley Saxons. Those to the west of Silchester may have been built in conjunction with the main section of the Wansdyke itself, leading west from Calleva along the Roman road which intersects, and was destroyed by, the Wansdyke.

Although Calleva's defences would have remained relevant throughout its survival, after the victory of Mons Badonicus and the peace which followed it, a new threat emerged from the south in the form of the West Seaxe, and the north-facing Wansdyke was no defence against it.

By 577, with the fall of three British kingdoms based around Gloucester (led by Caer Gloui), and the fall of Caer Gwinntguic to the south and southwest (probably in 552), Caer Celemion was totally isolated. It had the Thames Valley Saxons pressing it from the north and the much more powerful West Seaxe attacking from the south, and between about 600-610 it was destroyed, probably by Ceawlin of Wessex.

Unfortunately, there is no written record of the event. Despite almost certainly being the seat of a bishop in the fourth century in a conspicuously placed Christian church, by 634 Calleva's historic past had clearly been forgotten when Birinus chose the much smaller, and less significant, walled town of Dorchester-on-Thames as the centre of his mission to the West Saxons. Indeed Caer Celemion (Roman Calleva, modern Silchester in Hampshire) was certainly a centre of resistance by the British, as indicated by protective dykes that surround its northern borders. Legends exist of a giant named Onion living there. This indicates a potential leader, or king, called Einion. The appellation of "giant" could equate a strong or particularly tough warrior, appropriate for a British enclave that held out, almost entirely isolated, until the seventh century.

Map of mid 6th century when happened the "Battle of Dyrham", showing the area I borders occupied by the AngloSaxons conquerors (and defined by only a few not English names for the rivers).The battle was a major military, cultural and economic blow to the Romano-British because they lost the three cities of Corinium, a provincial capital in the Roman period (Cirencester); Glevum, a former legionary fortress (Gloucester); and Aquae Sulis, a renowned spa (Bath). Archaeological research has found that many of the villas in the post-Roman era were still occupied around these cities: this suggests the area was controlled by relatively sophisticated Romano-Britons. However they were eventually abandoned/destroyed as the territory came under the control of the Saxons. This quickly happened after the battle around the Cirencester region but the Saxons took many years to colonise Gloucester and Bath.

Caer Colun (Camulodunum)

A probable post-Roman British name for the important Roman town of Camulodunum (Colchester in Essex) and a potential kingdom or territorium based around it. There is no established British history for this region after internal British rule began, but although the Kingdom of the East Saxons (Essex) was founded circa 540, mercenaries are likely to have been settled along the coast for at least a century and a half before that date.

As with Caer Lundein, there is a marked lack of Anglo-Saxon relics in the area before the sixth century, which strongly suggests that Caer Colun could have held a surviving pocket of British power well into the mid-500s. That would also explain the comparatively late date for the founding of an East Coast Saxon kingdom.

Evidence from two Roman villa sites, at Little Oakley and Rivenhall, does demonstrate some early Saxon settlement in the territory. Distinctive early pottery from the filling of pits at Little Oakley provides evidence of occupation on the site of the villa, although it can tell us little about the nature of the settlement. Evidence from Rivenhall is more extensive and includes a post-built hall and a well, plus pottery and a glass vessel dating from the fifth century (AD 400-500).

This evidence of early Saxon settlers reusing Roman sites, and possibly even existing buildings and structures, is not unique to Essex, and parallels have been found, for example, at Darenth Roman villa site in Kent. What is unsure, however, is whether the evidence represents settlers using sites which were vacant, available, and easily converted for their use, or whether they were actually involved in the maintenance of the Roman estates, with the express permission of the existing landowner.

The mechanism and nature of the Saxon settlement of England, even on the level of how many foreign settlers arrived on these shores, remains unclear. What does seem certain, however, is that in Essex they did not encounter large-scale resistance from the natives. Also, the period from which these findings originate strongly suggests that they were from the settled Saxon laeti, and not the new wave of Saxons who began to infiltrate the region from the start of the sixth century.

After whatever Sub-Roman authority still existed in the region in the mid-500s presumably capitulated, Colchester seems to have become abandoned (which it certainly was by the seventh century)

Some sub-Roman territories or kingdoms are better attested than others. Those in the south-west may not have survived longer than some of their eastern counterparts, but they seem to be mentioned more often.

Caer Gloui - Glevum (with Caer Baddan and Caer Ceri)

To the south of Pengwern lay the Romano-British cities of Caer Gloui (Roman Glevum, modern Gloucester in Gloucestershire), Caer Ceri (Roman Corinum, modern Cirencester in Gloucestershire) and Caer Baddan (Roman Aquae Sulis, modern Bath in Somerset). The colonia of Gloucester was founded by Rome around the start of the second century.

It is known that small kingdoms existed here in the sixth century, although their names are not known. Ambrosius Aurelianus, strongly linked to the south west, also seems to be linked to Caer Gloui (and the 'three cities' territory), so perhaps this was his main base. It seems highly possible that the later splintered kingdoms were a single political entity in his time, and were subsequently handed out between descendants (Nennius calls the region Guenet).

In fact, the centre of Ambrosius' power in the mid- to late-fifth century can only lay in one of two places, and of those, Caer Celemion seems less likely. The three cities territory, lying in central Wiltshire, west of the hinterland of the Saxon Shore, and extending from upper Somerset to Gloucester was an area not yet remotely threatened by Cerdic and his people in Hampshire.

And here, strategically situated in the Avon valley, almost due south of the central section of East Wansdyke at Wodnesgeat, some fourteen miles away across the Vale of Pewsey, is Amesbury, which in a charter of about 880 was spelt Ambresbyrig, 'the stronghold of Ambrosius'. Nowhere could be better suited to be the focus of Ambrosius' operations.

According to archaeological evidence, Caer Ceri continued as a centre for civic life in the 440s; the defences were repaired, flood prevention work was carried out on one of the gates, and the piazza of the forum was kept clean. But in 443 the whole Roman world was swept by a plague, the severity of which has been compared to the Black Death, and this hit Britain in around 446. At the same time as the Anglo-Saxon mercenaries in the east revolted, unburied bodies were to be found in Caer Ceri's streets, and the town seems to have contracted to some small wooden huts inside the amphitheatre.

The Romano-British must have recovered from the mid-century plague. The next major event for the territory was Ælle's attack on Mons Badonicus in circa 496. The route the Saxon forces took was probably westwards along the upper Thames Valley and through the Goring Gap.

It seems creditable to assume that the north-facing "Wansdyke", constructed in the fifth or sixth centuries (and which roughly follows in part the proposed upper section of Caer Baddan's eastern border where it leads to the northwestern border of Caer Celemion), was put up by sub-Roman forces in Wiltshire in the face of just such a threat.

It could either have been constructed to ward off this very attack from the direction of the Thames Valley (and perhaps channel the attackers towards Badon), or in response to it, to ensure that no future attacks of this nature could take place. In that it was very effective, until the West Seaxe conquered the heart of Wiltshire in 552.

No doubt greatly heartened by their victory at the end of the century, the sub-Roman presence continued to hold out. For much of the early sixth century (at least until 534, and maybe as late as 560) they remained in general unmolested.

In 577, the West Saxons set great store by the fact that the final kings of the three cities were killed fighting them at the Battle of Dyrham (Gloucestershire). The territory was taken over by the Hwicce, who apparently merged with the existing Briton population. The West Wansdyke region of Caer Baddan seems to have remained in Dumnonian hands (or those of Glastenning) until 597-611, when it fell to the West Seaxe.

Eastern Dumnonia

On Britain's south coast, the modern Dorset area remained in British hands until at least the mid-seventh century.

Given the dominance of Dumnonia over the whole of the south west, it is unlikely there was an independent kingdom here, but either Caer Durnac (Roman Durnovaria, Dorchester in Dorset - from the former Durotriges tribe of this territory) or Wareham (the site of several early British memorial stones) may have hosted a regional power base, or sub-kingdom.

Its name is unknown but extrapolating from Dorset's modern name, and the fact that Saxon settlers in the area called themselves the Dornsaete, the name Dorotric, or Dortrig, is not impossible. Defnas (Devon) has also been used for the neighbouring area to the west, probably to indicate the Britons there.

Ceint (Cantiacum/Kent)

Nothing outside of the traditional story of Vortigern's betrayal by his Jutish foederati is known of post-Roman Kent. It cannot have remained a free territory for more than a generation before being captured by Hengist and Horsa between 450-455.

They were given land there in 450, and began their revolt later the same year. But Ceint was definitely a British kingdom in 450, and may have been established by the time Vortigern became High King in around 425. Its capital would have been Durovernum (Canterbury).

The story of its capture ascribed a King Gwyrangon as its ruler. Doubtless he became one of Vortigern's staunchest detractors when he found the High King had given his kingdom away to barbarians, but he must have put up a fight. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle depicts two major battles, Agæles threp (Aylesford in Kent) in 455 and Crecganford (Crayford) in 456, before the British are said to have given up on Ceint and retreated to London. One further defeat sealed Kent's fate.

Linnuis (Lindum/Lincoln)

The colonia of Linnuis, or Lind Colun, was founded by Rome around the start of the second century with the name "Lindum colonia".

The possible post-Roman kingdom of the same name was linked to the Lincolnshire region, and the names are remarkably similar, given the translation from Celtic to English. Linnuis appears in Nennius' list of Arthur's Twelve Battles, making up four of them.

These battles were fought one after the other, suggesting a series of strategic fights, or a running battle along one of Linnuis' rivers (Dubglas, the modern River Trent?). The aim must have been to push back an Anglian incursion, or a large scale Saxon raid. There were already Anglians settled in Deywr, on the other side of the Humber, although they appear to be mostly peaceful at this time.

On the other hand, the Saxons to the south were actively hostile, and the Historia Brittonum describes how, at "...Hengist's death, Octha his son went from the northern part of Britain to the kingdom of Kent".

Hengist died in 488, during the presumed height of Arthur's reign, so in theory Octha could have been recalled from an attempt to take territory in Linnuis.

The probable Celtic name of the capital of this region is Caer Lind Colun (modern Lincoln, Roman Lindum colonia, hence Lind(um) Colun(ia)). The name Linnuis would also appear to derive from that of the regional capital.

Linnuis appears to have be taken over early by the Anglian Lindiswaras from the region of the Humber, in circa 480 AD (perhaps as a result of territory ceded during the attacks postulated above?). That much is about all that is known in an area that was greatly isolated from the country by the extensive marshlands around The Wash (Metaris Aest.) to the south, the vast Sherwood Forest and the marshes of the River Trent to the west, and the Humber to the north.

Nothing is known of the Anglian Kingdom of Lindsey until the late eighth century, but it is possible that the Linnuis section of the Saxon Shore passed to them intact, and may have included some intermarriage between Angles and Romano-Britons.

Archaeological finds of British and Anglian pottery at the same site in a Saxon church at Barton-on-Humber supports the theory that there was no break in rule between British and Anglian governorship of Lindsey.

Ynys Weith (Inis Vectis - Wight island)

The Isle of Wight, or Inis Vectis, was either Romano-British until 530 AD, when it was conquered by the West Saxons, or it was seized much earlier by the Meonware Jutes from Hampshire, and the date of 530 is a later invention by the West Saxons.

While it was still British, however, it may have fallen under the control of Caer Gwinntguic, probably as a sub-territory, as became the accepted practise after the collapse of Roman authority. The Romano-British name of the military structure from which the island was governed is not known.

--------------------------------------------------------------------

Last but not least, I want to remember that sixty miles west of the Wight island -on the coast surroundings of modern Dorchester- there was the sub-roman settlement of "Durnovaria". This area remained in Romano-British hands until the end of the 7th century and there was continuity of use of the Roman cemetery at nearby Poundbury until the end of the next century. Dorchester has been suggested as the centre of the sub-kingdom of "Dumnonia" or other regional power base, that had some commerce with continental Europe.

Tintagel castle in Dumnonia is worldwide known as a possible link to the famous "King Arthur": in 1998, the "Artognou stone" was discovered on the island, demonstrating that Latin literacy survived in this region after the collapse of Roman Britain.

In 1998, this "Artognou stone", a slate stone bearing an incised inscription in a "modified" Latin, was discovered on the Tintagel island, demonstrating that Latin literacy survived in this western region during the Sub-Roman years and that probably the Romano-Britons of the region used a romance language (the "British Latin": read for further information https://web.archive.org/web/20140821232929/http://www.mun.ca/mst/heroicage/issues/1/hati.htm) for some centuries after the Roman legions departure.

Furthermore, in a village near Durnovaria archaeologists have found evidences of a limited Romano-Britons presence until the second half of the eight century: the oldest "testimony" of Sub-Roman Britain!. Click on the following map showing the village near Southampton:

Indeed the four centuries of existence of Roman Britain (until 410 AD) were followed by nearly four centuries of "diminishing" existence of Sub-Roman Britannia. The most dynamic urban activity of Sub Roman Britannia happened in the city of "Viroconium" (Wroxeter). Philip Barker's meticulous excavations of the baths basilica site revealed the constant repair and reconstruction of a Roman masonry structure into the mid fifth century. At that point, a large complex of timber buildings was constructed on the site and lasted until the late sixth century when they were carefully dismantled. Described by the excavator as "the last classically inspired buildings in Britain" until the eighteenth century, this complex included a two-storied winged house--perhaps with towers, a verandah, and a central portico--smaller auxilliary buildings (one of stone), and a strip of covered shops or possibly stables. More a villa than a public building, it was perhaps the residence of "tyrant" like Vortigern who had the resources to build himself "a kind of country mansion in the middle of the city" with stables and houses for his retainers.

Viroconium is estimated to have been the 4th-largest Roman settlement in Britain, a civitas with a population of more than 15,000. This important Romano Briton settlement probably lasted until the end of the 7th century or the beginning of the 8th (according to White and Dalwood; please read page 5 of their famous "Archaeological assessment of Wroxeter, Shropshire": https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archiveDS/archiveDownload?t=arch-435-1/dissemination/pdf/PDF_REPORTS_TEXT/SHROPSHIRE/WROXETER_REPORT.pdf).

Finally I want to pinpoint the existence of some isolated villages called "vicus" -in central and north Britannia- where Romano-Britons maintained their identity for some centuries (Sub-Roman Britain lasted nearly 4 centuries, from 410 AD to approximately the second half of the 700s), even if totally surrounded by the Anglo-Saxons: for example, just south of the Hadrian Wall there were a few "vicus" near Piercebridge Roman fort that possibly lasted until the 700 AD (read http://www.yorkshireguides.com/piercebridge_roman_fort.html) with a Roman bathhouse. Even in this case the reader can click on the bottom map to see the Piercebridge "vicus" in the year 700 AD:

Tuesday, October 1, 2019

Sunday, September 8, 2019

THE AROMANIAN NATIONAL REBIRTH

In my weblog in Italian language I have researched about the so called "Aromanian rebirth", that has happened with the development of nationalism in the Balkans since the XVIII century. Here it is a partial translation in English language of this research, titled in Italian "La rinascita degli Aromuni fino alla Grande Guerra" ('The rebirth of the Aromanians until WW1'). If interested read the original here: http://brunodam.blog.kataweb.it/2019/09/05/la-storia-recente-degli-aromuni/.

Map showing the territorial requests, at the 1919 Peace Conderence of Paris, for the creation of an Aromanian state in the Pindus region of northern Greece

THE AROMANIAN REBIRTH IN THE LAST TWO CENTURIES

The following text is based on a research by N.S. Tanasoca (a well-known Romanian writer) on the historical story of the Aromanians in the Balkans. I want to clarify from the outset that this translation in Italian comes to be the opinion - in some way partialized - of many writers and historians of Romania and that it does not coincide with the opinion of other writers, especially Greeks and Bulgarians.

Furthermore, I personally believe that - to save something of the aromanian presence in the southern Balkans, after the failure of the two attempts to create an aromanian State (one supported by France & Italy in the first world war and the other by Italy in the second) - all that remains is to renounce to the idea of an aromanian nation and to accept the Romania's support in creating a small Balkan area -with limited autonomy, inside other nations- with a "Romanian" dialect. In short, a kind of "reserve" of Aromanians, as it exists for Indians in the USA.

Only in this way could be prevented in the next few decades the total assimilation of the remaining aromanian areas in the Pindus, saving one of their substantial communities within a 'United Europe' (given that the aromanian presence -although official- in Albania and Macedonia is 'minimal and irrelevant').

Under the impact of historical circumstances, the Aromanians did not experience the phase of the full rebirth of small European nations in the 19th century and did not, therefore, become a standard ethnic group. However there was a kind of rebirth, but full of problems.

As Nicolae Tanasoca pinpointed, starting during the second half of the Eighteenth Century, a considerable number of Aromanians emigrated from the Balkan Peninsula because of certain economic concerns and political needs in an attempt to preserve their nationality. One can cite, in particular, the founding of some important settlements by Aromanian merchants, most of whom were born in Epirus and who were forced, as the result of Ottoman persecutions at the end of the Eighteenth Century, to settle in the Habsburg Empire (Austria, Hungary, and Transylvania). Then, after the First World War, came the efforts on the part of the Romanian government to colonize Dobrudja (at the mouth of the Danube river) with a few thousand Aromanian families. In addition to the latter, some compact Megleno-Romanian groups also settled on Romanian territory and preserved both their ethnic features and their language.

The settling of Aromanians in the Habsburg Empire is linked to the so called 'first Aromanian national renaissance'. Continuing a cultural direction undertaken as early as their presence in the Balkan Peninsula within the flourishing urban center of Moscopolis (that was destroyed by the Ottoman Ali Pasha of Yanina), those Aromanians who had emigrated to Central European cities came into contact with Habsburg Empire Romanians (chiefly Transylvanian Romanians ). Here, in the effervescent atmosphere of the 'Enlightenment', they developed a movement of cultural assertion in their own language which they tried to promote by writing grammars, primers, and even histories of their people. Focusing on the Romanity of Aromanians and even on recovered Romanity, this movement triggered the response of the Greek-Orthodox clergy grouped around the Oecumenical Patriarchate. They viewed the possible Aromanian departure from the cultural boundaries of a Hellenism that they had supported both intellectually and materially, as being akin to religious apostasy.

The 'second Aromanian national renaissance' began to take shape in the second half of the nineteenth century through the efforts of mid-century revolutionaries, also known in Romania as the Forty-Eighters. These revolutionaries, in their national aspirations to bring together all Romanians into one national state and to creatively assert the cultural identity of the Romanian people in its own language, did not want to exclude the Balkan Romanians.

Stages of the “Aromanian Issue” in the Development of Balkan Policy

Tanasoca also wrote that many pages of Balkanology have been devoted to the so-called national rebirth of the Aromanians in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Generally speaking, both Romanian and foreign researchers claim that this Aromanian national rebirth, identifiable at the level of both written culture and institutional life, was the result of an initiative taken by Romanian Forty-Eighters. These persons, owing to the mediation by outstandingémigrés in the aftermath of the 1848 Revolution, Christian Tell, Nicolae lcescu, Ion Ghica, Ion Ionescu de la Brad made contact with the Aromanians who lived in the Ottoman Empire. As a result, they experienced intensely the rediscovery of many distant “brothers” and decided to fulfil, as soon as possible, the ideal of reinserting them into the mass of a culturally and politically reborn Romanianism.

The schools were later followed by a similar network of churches in which religious services were conducted in Romanian. These actions marked the beginning of a Balkan Romanian policy intended to strengthen a status of cultural autonomy and to provide protection to the Aromanians by the Romanian State. Carried out with tenacity and diplomatic skill in the changing and often unstable circumstances of political life in the Balkan Peninsula, this action proved successful and remained a constant direction of Romanian foreign policy until 1945.

In terms of both political practice and the writing of history, the Aromanian issue was also a source of high-pitched confrontations and controversies between Romanians and other Balkan inhabitants. Romanian historians and statesmen considered the Aromanians to be “brothers” – or “first cousins”, in the words of René Pinon (1908) at the beginning of the Twentieth Century – of the Daco-Romanians, openly considering them Balkan Romanians or even Romanians who had emigrated, over the centuries, from ancient Dacia to the South. While these Romanians supported their distant relatives according to what they deemed to be a moral duty and a national political imperative, non-Romanian Balkan historians and statesmen claimed, with very few exceptions, that the Aromanians were not Romanians and that the intervention of Romania in their favour was a form of cultural imperialism, an act the hidden agenda of which was an attempt at political and territorial expansion and annexation.

Having reached the peak of its influence during the Balkan Wars, the Aromanian policy of Romania underwent a decline as further wars determined the dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire and the strengthening of Balkan national states. Thenetwork of Romanian schools and churches shrunk quite considerably and was only tolerated in Greece, owing to certain special circumstances.

The Second World War and the changes it brought about in the social and political structures of Southeastern Europe simply did away with the Aromanian issue and sealed the fate of Aromanians under the guise of a gradual, but increasing, de-Romanianization. Today, the “Aromanian issue” is no longer a political reality, but rather a topic of great interest for objective research that has so far been insufficiently developed.

The “Aromanian Issue” between 1879 and the First World War

Between 1879 and 1919 the Aromanian national rebirth reached its peak.

The year 1879 witnessed the founding of the Bucharest Society for Macedo-Romanian Culture. Chaired by Calinic Miclescu, the Primate of Romania, and having Vasile Alexandrescu Urechia as its secretary, the institution was led by a Council made up of thirty-five personalities. These included Dimitrie and Ion Ghica, Dumitru Brătianu, C. A. Rosetti, Ion Câmpineanu, Gh. Chiţt, Nicolae Ionescu, Christian Tell, Menelas Ghermani, Dr. Ioan Kalinderu, D. A. Sturdza, Titu Maiorescu, Vasile Alecsandri, and Ioan Caragiani. As it had a legal status, the Society represented the genuine core of the Aromanian rebirth movement. Although the Society was not a government body, it had highly unusual responsibilities, such as the right to issue documents attesting civil status, including certificates of nationality intended to assist Aromanians in obtaining Romanian citizenship with comparatively reduced bureaucratic efforts.

Since it was a representative structure for the Aromanians, the Society also guided and coordinated their education in the Romanian language. Its initial objectives were to establish a Romanian bishopric for Aromanians and a boarding school for young people who were studying in Turkey, to raise funds and to subsidize the publication of Aromanian journals and books, and to support the Church. Beginning in 1880, the Society issued an Aromanian journal called Brotherhood for Justice, but it could only continue this effort for one year. Still, in 1880, it published a Macedo-Romanian album with 173 Romanian and foreign contributions to the cause.

The fact that the Society for Macedo-Romanian Culture was founded in 1879 was not purely coincidental. Immediately after gaining full state independence in 1878, Romania had the opportunity to freely develop a foreign policy of its own and used this Society to express its legitimate claim to play a part in the Balkans. However, this claim never implied territorial annexations, only the strengthening of Aromanian cultural autonomy. The Society functioned until 1948.

On the eve of the Balkan Wars, there were over 100 Romanian primary schools in the Ottoman Empire, as well as several secondary schools, including a high school in Bitola and a trade school in Salonika. Although these schools all required their students to pay tuition fees, they were subsidized by the Romanian government. The Aromanian schools outside Romania were placed under the direct authority of the Romanian State that appointed all the teachers. They were also subordinated to a General Inspectorate.

For several decades, this Inspectorate was headed by Apostol Margarit. With the help of the French priest Jean Claude Faveryal, he supervised the birth of many Romanian schools for the Vlach population of the Ottoman Empire. Apostol Margarit dedicated many works to the Aromenian question - Raport despre persecuŃiile şcoalelor române în Macedonia din partea Grecilor in 1875; Réfutation d'une brochure grecque par un Valaque épirote in 1878, Etudes historiques sur les Valaques du Pinde in 1881, Les Grecs, les Valaques, les Albanais et l'Empire turc par un Valaque du Pinde in 1886; La politique grecque en Turquie in 1890; Memoriu privitor la şcoalele de peste Balcani in 1887.

The Romanian schools in the Ottoman Empire were highly successful. They produced generations of graduates, many of whom later chose to settle in Romania. Yet, the main problem for these schools was that of persuading Aromanians to remain in their native environments. This goal could not be accomplished. Indeed the other Balkan nationalities displayed an open hostility to the Romanian education system, for they were competing for the Ottoman legacy even before the formal collapse of the Empire, ready to partition it as best they could. The support of Romanianism could be interpreted as engaging in open combat against all the Christian nationalities in Macedonia.

As for church organization, its progress did not match the positive evolution of the education system. Although on 16 June 1889, the Patriarchate finally permitted the use of the Romanian language in churches built by Aromanians, its attitude, in principle, remained aloof, if not hostile, either openly or through well-hidden manoeuvres. On 27 June 1891, a Sultan’s "irade" (decree) was promulgated, authorizing the use of the Romanian language in Aromanian churches and the use of Romanian books during religious services. Despite all efforts and in spite of an attempt, in 1896, to elect Antim, who was known to support the Aromanian cause, as the Ohrid metropolitan bishop, there were no possibilities of establishing an Aromanian bishopric able to free the Aromanians from the authority of the Greek church and to support their unhindered development.

Catholic propaganda, conducted mainly by a Lazarist named Faveyral of Bitola, was strongly directed toward the conversion of the Aromanians. Apostol Margarit was linked to certain attempts to bring about a religious union with Rome. But the Aromanian community was too attached to the Orthodox tradition to make such a shift. This tradition was a critical element in its national consciousness.

For some years a church in Voskopojë was managed by the Aromanian priest Cosma Demetresescu even after he was closed in a monastery, in 1891. In the same year another decree allowed Aromanians to use their language not only in the religious functions but also in the ritual books. The first years of XX century continued to stage violent attacks on Aromanian clergymen and notables, while romanian diplomacy increased its efforts to obtain from the Sultan privileges as the creation of an indipendent patriarchate. In 1903 Aromanians were among the victims and at the same time the partecipants of the Ilinden insurrection (in the Soviet of Krushova republic there were around 20 Aromanians and later, in the reform commission apponted by the Turks there was the Romanian Pandele Maşu). In 1903 an Aromanian cemetery was set in Monastir while in 1904 a Romanian consulate was opened at Yanyna.

The sympathies showed towards the Sultan were soon repaid and in 1905 sultan Abdul Hamid issued a decree ("irade") to grant Aromanians all the rights of a millet with the exception of a religious head, creating in this way the "Ullah millet". The irade of 22th May 1905 granted to the Vlachs the use of their language in religious matters and the freedom of electing mayors (muhtar). But it caused many angry protests among Greek ecclesiastical authorities, starting from the patriarch Joachim. Besides the opposition of the Greek priests, the irade caused the violent reaction of the bands born to fight the Bulgarian "komitadji". The repression of Aromanian rights included the killing of clergymen, the denial of the Sacraments and violent attacks against the attendants of Aromanian schools

According to Italian military sources, violence continued to mark the inter-ethnic relationships in the Balkans, as denounced by the Romanian press which continued to invoke drastic measures against the discriminatory and violent treatment of the Aromanians by bands of Greeks (and also of Bulgarians and Albanians, but in a minor scale). "Aromanul" (13th November 1913) protested against the assassination of some Romanian activists (Dem. Zicu of Petrici and Mitra Arghieri of Şatra), "Viitorul" (Rominii maeedoneni, 20th December 1913) and "Fulgerul" (Exterminarea Aromanilor, 20th January 1914) against the risk Aromanians could disappear; “Dreptatea" (Romanii albanezi şi asasinarea preotului Balamace, 26th March 1914) and “Adevarul" (Un mitropolit bandit, 29th March 1914) talked abut the fury caused by the murder of the Romanian bishop Haralambie Balamace and accused the Greek metropolit Ghermanos. Finally other protests were caused by the Greek response given by Venizelos, who accused the Albanians of having comitted the massacres of the Aromanians in Coritza (Guvernul şi masacrele din Corita, in “Adevarul", 30th March 1914; Incorigibilii, in “Mişcarea", 3rd April 1914).

Happily satisfied by the recognition of both their ethnic individuality and their cultural and administrative rights, the Aromanians after only 8 years were dealt a harsh blow in the aftermath of the Balkan Wars. The August 1913 Treaty of Bucharest sealed the establishment of national states in the European territories of the Ottoman Empire and divided the Aromanians among these states. Their cohesion was thus shattered, and they were left at the mercy of various national governments that had made no formal commitment to respect Aromanian ethnic autonomy and national rights.

During the first years of WW1, when Greece was divided between Ententists and supporters of the Central Powers, the Pindus Aromanians began an insurrectional movement with Italian support in order to establish, in the Pindus region, an Aromanian political body, completely independent of Greece. Supported by the Society for Macedo-Romanian Culture and by certain Romanian personalities, this movement was exploited by other political actors to obtain recognition of Romanian claims to the whole region of Banat.

But later, represented at Versailles by a delegation led by George Murnu, the Aromanians found themselves in a no-win situation. The Utopian intention to establish an Aromanian or an Aromanian-Albanian state was invalidated by Balkan and general realities. The geographical characteristics of the area concerned failed to provide for economic self-sufficiency. The Aromanians were overly dispersed throughout this area and were surrounded by more numerous neighbours who opposed the whole idea. Finally, there was a lack of consensus among Pindus Aromanians in favour of such an arrangement. The frailty of the dream of a Romanian-Albanian state could be observed in the treatment that Albania meted out to its Romanian minority. The Albanian state did its best to do away with all educational and religious activities carried out by the Aromanians and quickly took the next logical step, that of questioning the very existence of Aromanians on its territory.

The French and Italian intervention

In 1914, in the aftermath of Balkan wars, an Autonomous Republic of Epirus was formed around Gjirokastër. It was led by a distinguished local Greek politician, Georgios Christakis-Zogràfos, who referring to the Megàli idèa gave birth to an autonomous administration, put under formal Albanian sovereignty and recognized also by the Great Powers with the Protocol of Corfu. The experiment took also to the creation of an autocephale church whose chiefs soon reconciled with Athens. The end of the principate was then followed by a period of Greek administration and, after the division between royalists and Venizelos’ supporters had thrown Greece into an unstable position, by the arrival of French and Italian troops at Korcë and Gjirokastër.

The two provinces of Korytsa and Argyrokastro were inhabitated by a melting pot of creeds and populations and included also some Vlachs. During the Epirus autonomy, the Greek administration viewed all Albanian Aromanians as part of the Greek minority without taking into account their different nationality. The region later fell under the control of the Bulgarians, who tried to join Austrian allies, before being stopped by French intervention. Also some groups of rebels were active in the region of Korçë, one was led by Themistokli Gërmenji and another by Sali Butka. The latter, sacked completely the Aromanian Moscopole and threatened with the same perspective Korçë.

When the city of Koritza came under French control, the French tried to get a compromise and an "Autonomous Albanian Republic of Korçë" was established with a council made up of seven Christians (someone Aromanian) and seven Muslims and with Themistokli Gërmenji as prefect of police. The new authorities introduced Albanian as the official language and replaced Greek schools with Albanian ones, which had been forbidden during the Greek administration of the city.

Italy reacted against this French policy aimed at influencing Albanian affairs and, as Italian armies were also present in many parts of Albania - the port of Vlorë and the southern region of the Albanian principality- proclaimed Albanian indipendence and tried to counter-balance French dominion.

In 1917, when Italian troops advanced into Albania they were welcomed in all Aromenian villages, for example in Ciamuria and Samarina. A National council for Pindus was created and it took a very pro-Italian attitude. They later founded, with the help of some local representative as Alkiviadis Diamantis, the "Principate of Pindos" in the area of Aromanian settlement. Italy undertook attempts to convert the proRomanian Aromanians into pro-Italian one, taking advantage of the historical and language relations these communities had with Italian latinity. In this particular context, Italian military forces felt the need to improve the ethnic and political conditions of the Aromanians, and sketched some documents on their history and customs. Their villages could be distinguished for the solidity and a certain elegance and were often placed in positions of military interest, next to the mountains and road junctions. The Aromanians were described as calm, wealthy, occupied in trade or sheep-breeding, resistant to any persecution or massacre, even though the denaturalization policies pursued by the Greeks, as reported by colonel Casoldi on 29th May 1917 in his account 'Note circa la questione valacca'.

The Aromanian presence was particularly evident in two districts, Grammos – expecially in the city and around Koritza - and Pindus, where 36 villages were clearly detachable. Even if they were not as populous as the old Moscopole, these settlements mantained their ethnic identity. The language, instead, was in some case abandoned, also as a consequence of the Greek propaganda, pressures and abuses. Aromanians even arrived at creating national armed bands against those sent by Greeks to terrorize the region and this resistance was considered almost incredible by Italians, due to the peaceful and calm traditions of the Aromanians. It was also noted that many Aromanians enlisted in the Romanian army staying in Moldova asked to be sent back to the Balkans to fight for the security of their lands.

Trying to conquer the sympathies of those communities, the Italians thought that the strategy to follow was that of sponsoring the birth and increase of local authorities in order to prepare for the peace negotiations a fertile ground for the establishments of cantons or political and administrative autonomy. These hopes were increased also by the demands of Aromanian communities, who after the years of the Greek-Romanian dispute and the troubles of war searched in the kingdom of Italy a stronger protector.

Pindus Aromanian villages which signed a letter sent from Samarina and Metzovo to US President Wilson, Italian authorities and Romanian Prime Minister I. C. Brătianu asking "autonomy" on the 27th July 1917: 1)Samarina (Samarina-Σαμαρίνα);2)Abella (Avdella - Αβδέλλα Γρεβενών);3)Perivole (Περιβόλι Γρεβενών);4)Baïassa (Βοβούσα Ιωαννίνων);5)Amintchou (Metzova - Μέτσοβο);6)Paléosseli (Παλαιοσέλλι Ιωαννίνων);7)Padzes (Πάδες Ιωαννίνων);8)Tourïa (Κρανέα Γρεβενών);9)Breazna (Δίστρατο Ιωαννίνων);10)Laca (Λαΐστα Ιωαννίνων);11)Dobrinova (Ηλιοχώρι Ιωαννίνων);12)Armata (Άρματα Ιωαννίνων);13)Zmixi (Σμίξη Γρεβενών)

On 27th July 1917 the Italian commander in Valona, General Giacinto Ferrero, received a telegram coming from the mayors of many Aromanian villages who met in Metzovo, representing the Pindus-Zagori people.

“Figli non degeneri di Roma sempre memori della madre nostra antica e tenaci custodi della lingua e delle tradizioni dei nostri padri dopo lunghi secoli di lotta sanguinosa contro la straniero che tentava tutti i modi di cancellare nostro carattere nazionale latino respiriamo finalmente le pure aure della libertà che le nuove legioni di roma vittoriose agli ordini vostri hanno apportato ai loro fratelli di sangue dispersi lontani sul Pindo e Zagori” ('Non-degenerate children of Rome always mindful of our ancient mother and tenacious guardians of the language and traditions of our fathers after long centuries of bloody struggle against the foreigner who tried always to cancel our national Latin character, we finally breathe the pure auras of freedom that the new legions of Rome victorious on your orders have contributed to their scattered blood brothers on the Pindus and Zagori')

Besides the enthusiastic recalling of ancient Roman roots, in this appeal the Aromanians underlined the security given to them by the Italian troops; their leaving would mean falling easily prey of the enemies who looked forward to the extermination of Aromanians. The latter invoked Italy and her powerful and careful protection, the only means of defence against the superiority of the enemies. Finally, the signataries self-appointed themselves the 'sons of Rome', who throughout millenary events had kept intact and preserved the remembrance of the Roman civilization in the valleys and the mountains of Pindus. Even if in a shorter form, the same declarations were included in the comunication sent the same day to the President of the United states, to the president of the Provisory Russian Government, to the Romanian Prime Minister I. C. Brătianu, to the Belgian Foreign Affairs minister, to the French, English and Russian consuls in Yanina, to General Ricciotti Garibaldi in Rome and to the mayor of Rome.

In late 1918 a "memorandum" of the Aromanian people was sent to the 'Peace Conference in Paris' through the volume "Les Macedo-Roumains (Koutzo-Valaques) devant le Congrè de la Paix" redacted by the National Council of the Pindus Roumanians and signed by G.Munru, Nicolae Tacit, Arghir Culina, T. Papahagi. Besides the historical connection, the Aromanians recalled their will of joining the Roman Catholic Church repairing “le plus grave erreur historique” (their biggest historical mistake) and restablishing the relationships that Kalojan Asan had with the Pope, which proved the never-ending Latin character of the Aromanian people Italy was the natural benchmark of the Aromanians and her prestige deriving from the victory of the war increased her power and attraction towards the Aromanians, who kept on invoking Italian protection for the safeguard of their Latin culture. At Delvino, on 28th December 1918 and 10th January 1919, a special Assembly was convoked. The meeting defined a precise political project: the autonomy of Pindus and Zagori united with Albania and under the protection of Italy and pointed out a strategy to avoid any other undesired solution.

But the Paris Peace conference was not favorable to the Aromanians.

After 1919

The years, 1919-1948, represented a period of stagnation and decline in the evolution of the Aromanian issue. The Turkish-Greek War that ended with the Treaty of Lausanne of 1923 entailed the resettlement in Greek Macedonia of over one million Greeks from Asia Minor. This act was a truly finishing stroke for Aromanians in Greece.

Aromanian shepherding was destroyed by the parcelling of the large pastures so that all the newcomers could receive a piece of land. The latter were protected in the practice of the liberal professions and in trade through a process perceived as a threat by Aromanians who suddenly faced competition. The situation being what it was, those Aromanians who were still keen on their Romanity decided to emigrate to Romania. With the support of the Romanian State, the Dobrudja Quadrilateral was settled by several thousand Aromanians who were then forced to move into Romanian Dobrudja, when the Quadrilateral was retroceded to Bulgaria, in 1940. To this systematic movement of people, must be added the more gradual emigration of all the Salonika and Grebena secondary school aromanian graduates to Romania during the 1920s and 1930s.

The last intervention of Italy happened during WW2, when the Aromanian leader Alkibiades Diamantis created -under Italian control- the "Principate of Pindus" with the support of one thousand Aromanian volunteers of his 'Roman Legion', but the Axis defeat in this war left a complete destruction of the aromanian rebirth as a possible small State. Alkibiades Diamandis and his Aromanian troops of the 'Roman Legion' in 1941

Alkibiades Diamandis and his Aromanian troops of the 'Roman Legion' in 1941

Map showing the territorial requests, at the 1919 Peace Conderence of Paris, for the creation of an Aromanian state in the Pindus region of northern Greece

THE AROMANIAN REBIRTH IN THE LAST TWO CENTURIES

The following text is based on a research by N.S. Tanasoca (a well-known Romanian writer) on the historical story of the Aromanians in the Balkans. I want to clarify from the outset that this translation in Italian comes to be the opinion - in some way partialized - of many writers and historians of Romania and that it does not coincide with the opinion of other writers, especially Greeks and Bulgarians.

Furthermore, I personally believe that - to save something of the aromanian presence in the southern Balkans, after the failure of the two attempts to create an aromanian State (one supported by France & Italy in the first world war and the other by Italy in the second) - all that remains is to renounce to the idea of an aromanian nation and to accept the Romania's support in creating a small Balkan area -with limited autonomy, inside other nations- with a "Romanian" dialect. In short, a kind of "reserve" of Aromanians, as it exists for Indians in the USA.

Only in this way could be prevented in the next few decades the total assimilation of the remaining aromanian areas in the Pindus, saving one of their substantial communities within a 'United Europe' (given that the aromanian presence -although official- in Albania and Macedonia is 'minimal and irrelevant').

Under the impact of historical circumstances, the Aromanians did not experience the phase of the full rebirth of small European nations in the 19th century and did not, therefore, become a standard ethnic group. However there was a kind of rebirth, but full of problems.

As Nicolae Tanasoca pinpointed, starting during the second half of the Eighteenth Century, a considerable number of Aromanians emigrated from the Balkan Peninsula because of certain economic concerns and political needs in an attempt to preserve their nationality. One can cite, in particular, the founding of some important settlements by Aromanian merchants, most of whom were born in Epirus and who were forced, as the result of Ottoman persecutions at the end of the Eighteenth Century, to settle in the Habsburg Empire (Austria, Hungary, and Transylvania). Then, after the First World War, came the efforts on the part of the Romanian government to colonize Dobrudja (at the mouth of the Danube river) with a few thousand Aromanian families. In addition to the latter, some compact Megleno-Romanian groups also settled on Romanian territory and preserved both their ethnic features and their language.

The settling of Aromanians in the Habsburg Empire is linked to the so called 'first Aromanian national renaissance'. Continuing a cultural direction undertaken as early as their presence in the Balkan Peninsula within the flourishing urban center of Moscopolis (that was destroyed by the Ottoman Ali Pasha of Yanina), those Aromanians who had emigrated to Central European cities came into contact with Habsburg Empire Romanians (chiefly Transylvanian Romanians ). Here, in the effervescent atmosphere of the 'Enlightenment', they developed a movement of cultural assertion in their own language which they tried to promote by writing grammars, primers, and even histories of their people. Focusing on the Romanity of Aromanians and even on recovered Romanity, this movement triggered the response of the Greek-Orthodox clergy grouped around the Oecumenical Patriarchate. They viewed the possible Aromanian departure from the cultural boundaries of a Hellenism that they had supported both intellectually and materially, as being akin to religious apostasy.

The 'second Aromanian national renaissance' began to take shape in the second half of the nineteenth century through the efforts of mid-century revolutionaries, also known in Romania as the Forty-Eighters. These revolutionaries, in their national aspirations to bring together all Romanians into one national state and to creatively assert the cultural identity of the Romanian people in its own language, did not want to exclude the Balkan Romanians.

Stages of the “Aromanian Issue” in the Development of Balkan Policy

Tanasoca also wrote that many pages of Balkanology have been devoted to the so-called national rebirth of the Aromanians in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Generally speaking, both Romanian and foreign researchers claim that this Aromanian national rebirth, identifiable at the level of both written culture and institutional life, was the result of an initiative taken by Romanian Forty-Eighters. These persons, owing to the mediation by outstandingémigrés in the aftermath of the 1848 Revolution, Christian Tell, Nicolae lcescu, Ion Ghica, Ion Ionescu de la Brad made contact with the Aromanians who lived in the Ottoman Empire. As a result, they experienced intensely the rediscovery of many distant “brothers” and decided to fulfil, as soon as possible, the ideal of reinserting them into the mass of a culturally and politically reborn Romanianism.

The schools were later followed by a similar network of churches in which religious services were conducted in Romanian. These actions marked the beginning of a Balkan Romanian policy intended to strengthen a status of cultural autonomy and to provide protection to the Aromanians by the Romanian State. Carried out with tenacity and diplomatic skill in the changing and often unstable circumstances of political life in the Balkan Peninsula, this action proved successful and remained a constant direction of Romanian foreign policy until 1945.

In terms of both political practice and the writing of history, the Aromanian issue was also a source of high-pitched confrontations and controversies between Romanians and other Balkan inhabitants. Romanian historians and statesmen considered the Aromanians to be “brothers” – or “first cousins”, in the words of René Pinon (1908) at the beginning of the Twentieth Century – of the Daco-Romanians, openly considering them Balkan Romanians or even Romanians who had emigrated, over the centuries, from ancient Dacia to the South. While these Romanians supported their distant relatives according to what they deemed to be a moral duty and a national political imperative, non-Romanian Balkan historians and statesmen claimed, with very few exceptions, that the Aromanians were not Romanians and that the intervention of Romania in their favour was a form of cultural imperialism, an act the hidden agenda of which was an attempt at political and territorial expansion and annexation.

Having reached the peak of its influence during the Balkan Wars, the Aromanian policy of Romania underwent a decline as further wars determined the dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire and the strengthening of Balkan national states. Thenetwork of Romanian schools and churches shrunk quite considerably and was only tolerated in Greece, owing to certain special circumstances.

The Second World War and the changes it brought about in the social and political structures of Southeastern Europe simply did away with the Aromanian issue and sealed the fate of Aromanians under the guise of a gradual, but increasing, de-Romanianization. Today, the “Aromanian issue” is no longer a political reality, but rather a topic of great interest for objective research that has so far been insufficiently developed.

The “Aromanian Issue” between 1879 and the First World War

Between 1879 and 1919 the Aromanian national rebirth reached its peak.