Historically, accomplished Christian Berbers include famous writers such as Martianus Capella and Apuleius, Christian saints such as Cyprian and St. Augustine, Roman popes such as Pope Victor I and even the Roman emperor Septimius Severus. They appeared in a socio-cultural period of development in Roman Africa following the introduction of Christianity. Most of these figures are historical & related to the Classical era, because the Christians in North Africa actually do not have as much of a dominant community as they used to have in Roman times: indeed there was a huge & complete diffusion of Christianity between Berbers, during the Roman rule of the actual Maghreb in Antiquity (read http://www.30giorni.it/articoli_id_3553_l3.htm ).

When lived the most famous Christian Berber in Antiquity, Saint Augustine, there were five million inhabitants (nearly all more or less Latinized Berbers, with some Roman colonists descendants) in the provinces of the Roman empire that now are called the "Maghreb", but -after the 50 years of Muslim Arab conquests- there were only one million Berbers (while nearly all the Roman colonist descendants were murdered or flew back to Italy) in 705 AD: this was one of the biggest massacres registered in History, with the bloody end of Christianity in the region. Arab historians reported that in those years only in the Damascus market were sold as slaves 300,000 Christian Berbers. Roman Carthago was reduced from 500,000 inhabitants during Trajan/Hadrian years (it was the second biggest city of the empire) to a village full of ruins with just 3,000 survivors (of course all Muslims) in 705 AD.

Saint Augustine and his mother Saint Monica

Notable Christian Berbers

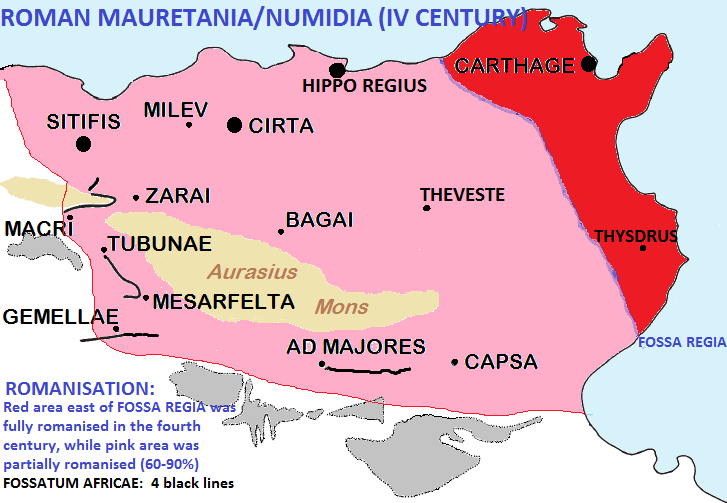

Famous historian Theodore Mommsen wrote in his famous "The Provinces of the Roman empire" that, at the beginning of the century when happened the fall of the Western Roman Empire, practically all the Berbers living inside the borders of Roman Africa were Christians.

Christian Berbers were Roman writers such as Terentius, Lactantius, Martianus Capella, Marcus Cornelius Fronto, Apuleius and Tertullianus. Christian saints included Scillitan Martyrs, Cyprian, Victor Maurus, Saint Monica and Saint Augustine (and even Roman popes like Pope Victor I, Pope Miltiades, Pope Gelasius I). Roman emperors such as Septimius Severus, Macrinus and Emilianus were also famous Christian Berbers.

Christian Berber kings of exclusive Christian Berber realms known as the "Romano-Berber states" includes Masuna of Garmul or the Kingdom of Altava. They are known for making Christian "jedars" and mausoleums such as the "Tomb of the Christians" near Caesarea of Mauretania (also known as the "Royal Mausoleum of Mauretania").

History

Roman empire

The first record of Christians in Africa is a document known as the "Acts of the Martyrs scillitans" dating from 180 AD, during the Roman empire era. The Acts document is related to the martyrdom of a dozen Christian (known as Scillitan Martyrs) in a berber village of Africa Proconsularis, which is yet to be named, in front of the proconsul of Africa.

However the major figures in early Christian North Africa was Tertullian, (born of pagan parents; a Roman centurion father and possibly a Romanised Berber mother) who joined the Christian community in Carthage in 195 AD and became close to the local administrative elite, who protected him from pagan repression against his religion. After becoming a priest, he argued in his early writings that Christianity should be recognized as a legitimate religion by the Roman Empire.

"African Christianity" between Berbers grew in followers after Tertullian found a way to merge Christianity with popular Berber life through religious doctrine. This would conflict with the Roman institutions promoting pagan worship at the time. The most major cause of anger between the two sides was the refusal of Christians to serve in the Roman army. For Tertullian Christians joining the army and killing opponents, hence violating the sixth commandment, was a great dilemma. The Romans began to persecute early Christians as they were hence endangering the Roman Empire by refusing military service (this period was a time of dire need for enrolling more soldiers in the Roman legions): Tertullian provoked the authorities until they lead to killing Christians, making them martyrs. It is a known fact the African Church began with martyrdoms. Tertullian later wrote about the rapid growth of Christianity among Africans, and how it had spread across North Africa to eventually reach peoples south and southeast of the Aures mountains.

Around the year 200 AD there was a violent attack at Carthage and in provinces held by the Romans against Christians. This was the persecution in which St. Perpetua died, which we know of from the writings of Tertullian. Despite persecution, Christinaity did not cease to expand. Christian epitaphs were found at Sour el Ghozlane in 227 AD and Tipasa at 238 AD.

By the third century there was a substantial Christian population in Africa. It consisted not only of the poor but also those of the highest rank. A council held in Carthage around the year 220 AD attracted 18 bishops from Numidia. By the middle of the third century, another was held which was attended by 87 bishops. Though at this time the African Church suffered a crisis. Emperor Decius published an edict to persecute Christians further. Bishops -followed by their whole communities- were planned to be executed. Many people had already bought certificates of apostasy for money, so much that they believed they could command the church by the law, and demand their restoration to communion. So, a lot of controversy was seen at this period.

Conflict between Catholics and Donatists

When Constantine arose to power the African Church had become torn apart by heresies and controversies. Catholics and Donatists (the first Christian group in History with "protestant" attitude) conflicted for power in a violent way. In 318 AD emperor Constantine deprived Donatists of churches, most of which had been taken from Catholics. The Donatists were so numerous that this could not stop them and a Donatist council held at Carthage in 327 AD was attended by 270 bishops. Attempts by Constantius II at reconciliation only lead to armed repression. Gratus, the Primate of Carthage, declared in 349 AD that "God has restored Africa to religious unity." However, with Emperor Julian's accession in 361 AD and his permission to allow all religious exiles back to their homes, the African Church saw more troubles. Donatist bishops were centered around a seceded see in Carthage opposed to "orthodox" (meaning 'pro-pope') bishops. One act of violence followed another and bred new conflicts. Opatus, Bishop of Milevi, wrote works fighting this sect.

St. Augustine, converted at Milan, returned to his home land and defended the Pope. Soon and thanks to him, 'Paganism' was no longer a menace to the church. In 399 AD all pagan temples were closed in Carthage. From 390 to 430 AD, the Councils of Carthage discussed with Donatists, gave sermons, homilies and scriptural commentaries persisted almost without stop. Augustine had managed to train clergy and instruct the faithful that Christianity was now strong in Africa. In 412 AD the Council of Carthage condemned "Pelagianism". Donatism, and Semi-Pelagianism were done away with at a time which changed the history and destiny of the African Church. There was Conflict between Carthage and Rome on how the African Church would be run, when Apiarius of Sicca appealed his excommunication to Rome and thus challenged Carthage.

Vandal Invasion

Count Boniface summoned the Vandals to Africa in 426 AD, and by 429 AD the invasion was complete. The Vandals conquered many cities and provinces. Nine years after Augustine died in 430 AD, during the siege of Hippo, king Geiseric of the Vandals took Carthage. The Vandals were Arians. They established their Arianism and set about destroying Catholicism. Churches surviving the invasion were to be transferred to the Arians or closed to public worship. This was only stopped briefly when Emperor Zeno intervened and made an agreement with Geiseric that the Catholics be allowed to choose a bishop. This was in 476 AD. Hunneric, the new king following the death of Geiseric, passed in 484 AD an edict which made matters much worse. The Christians of Africa did not display much resistance to this persecution, even in this terror, as writer Victor of Vita has told us.

Later in the Vandal rule in Africa, St. Fulgentius, Bishop of Ruspe, managed to influence the princes of the Vandal dynasty, who had become more Roman and Byzantine in culture. The Vandal monarchy, which had lasted for nearly a century, was also dwindling in power. The Vandals permitted the creation of some Romano-Berber states at their borders; but were later conquered by the Byzantine Empire, which established an African prefecture, later the Exarchate of Carthage. At this point some paganism was still worshipped in the Atlas mountains despite the strong Christian influence in Africa.

However Pope Gelasius I was able to convert all the pagans of the Aures who became the most loyal Christians (who ended up defending Romanised north-western Africa to the death with their queen Kahina during the Muslim invasion centuries later).

Romano-Berber States

The "Neo-Latin" states in North Africa are called so as they were post-Roman. They were no longer under Roman Empire authority, while Byzantine rule in Africa was collapsing. Their culture was a special form of Latin mixed with the local Berber language and the Christian religion.

The Christians living there initially followed a Christian sect previously mentioned known as Donatism. By the 6th century they only existed within communities of Berber Christians. The Christian kings of the Romano-Berber states left Djeddars. The Byzantines had never managed to conquer land far from Carthage, leaving these states alone for much of their development. The African Church was in decline. The Byzantine invasions had not given it any more of a base it had during the Vandal rule. The church was ridden with those who had failed their duties and those involved in fruitless and petty theological debates. Pope Gregory the Great attempted to send priests to Africa to help deal with this issue. The priest Hilarus became a papal legate and had authority over African Bishops, he reminded them of their duty and instructed them. He had managed to help restore peace, unity and discipline among the African Church. Justinian also helped strengthen the Romano-Berber's Christian elements by establishing Christian centers such as the one in Septem.

Neolatin-Christian Berber Kingdoms Arab Invasion

This new revival of Christianity did not last long. The Arabs, who had conquered Egypt, were on their way to Berber Africa. In 647 AD the Caliph Othman ordered and attack on North Africa, and gained a victory at Sbeilta against Byzantine and Christian Berber armies. He only withdrew when payed a large ransom. The African church remained loyal to Pope Martin around the time frame of 649 to 655 in his conflicts with the Byzantine Emperor. The last few decades of the 7th century saw the fragments of Byzantine Africa fall into Arab hands.

Indeed at the time of the death of the Arab "Prophet" Mohammed in 632 AD, his Muslims ruled only in Arabia. But within ten years the Arab Muslims had achieved one of the most spectacular conquests in history. They conquered Palestine (635-636), Syria (638-640), and Egypt (639-642) from the Byzantines and first Iraq (635-637) and then Persia itself (637-642) from the Persians. Wherever they went, most of the people were forced to become Muslims and Arabic-speakers. The converted people forgot their language and identity and started considering themselves to be Arabs. This happened with Palestine (today’s Israel), Syria, Levant (today’s Jordan), Egypt, Libya, Algeria, Tunisia, Morocco and also partly with Sudan, and Somalia. This trend was reversed only in Persia, where the people, in spite of the brutal Arab conquest, re-asserted their pre-Islamic Persian language after three hundred years of Arab rule. But everywhere else the Arab conquest, Arabized the Middle East and North Africa permanently.

A few Berber tribes converted to Islam without much resistance, but most of the Berbers opposed strong resistance under the queen Kahina who was able to force the Arabs to withdraw to Egypt & Cyrenaica. She ruled a Christian Africa for five years; but the Arabs returned with a stronger and powerful army: Carthage fell initially in 695 AD. It was soon reconquered by the Christians and again lost but this time forever. In 698-702 AD all the major capitals in the Berber states were taken definitively by the Arabs: Christian Carthago was completely destroyed, half the inhabitants were killed (only a few hundreds could escape by boats toward Byzantine Sicily) and the rest enslaved, erasing forever the main center of Greco-Roman influence in the Maghreb.

Musa bin Nusair, a successful Yemeni general in the campaign, was made governor of "Ifriqiya" and given the responsibility of putting down a renewed Berber rebellion and forcefully converting the population to Islam. Musa and his two sons prevailed over the rebels, slaughtered nearly all the Christian Berber civilians of his Ifriqiya and enslaved 300,000 captives (in those years the total population of the Maghreb was around one million, and this gives an idea of the massacre and why Christianity disappeared). The caliph's portion was 60,000 of the captives. He sold into slavery these Christian Berbers (mainly in Damascus, after a deadly deportation trough the desert from southern Tunisia to Egypt): the proceeds from their sale went into the Arab public treasury.

North Africa was eventually totally conquered until the Atlantic ocean in 709 AD by the Islamic Umayyad Caliphate; by this time Christianity in Africa was to be ended for several centuries. The church was fragmented and still suffering from the aftermath of fragmentation and the so-called Donatist heretics. But a few pockets of Christian rule existed for several centuries.

After the Arab Conquest

A few Christians in North Africa still existed even in the 9th century. Though they were no longer numerous, they were mainly found in major towns. Paradoxically the Christians who survived were those who had been the weakest worshipers, those in Morocco, mainly because the Muslim invaders left them alone and they were unfazed by the Vandal and Byzantine invasions.

The main communities of Christians were centered around Volubilis, their influence never stretched much past Tangier and Ceuta. However, from the 7th century onwards they were administered by a council of Christians with Latin names. They were open to Christians fleeing Arab invasion. An 8th-century manuscript mentions a Christian overseer at Tangier, and by 833 the church in Ceuta still had an Overseer. In 986, geographer el-Bekri found a Christian community with a metting hall at Tlemcen in Algeria. Brief Latin inscriptions still existed at the end of the 10th century in En-Ngila, Libya, and even as late as the mid-eleventh century in Kairouan.

Even by the 11th century letters were still being written to Christian leaders in North Africa; these letters were in Latin, showing evidence for the survival of that language among Romano-Berbers. The Overseer in Gummi (Mahdiya), Tunisia, mentioned a good-sized Christian community existing in around 1053 at Ourgla. The traces of Christianity had become so sparse, though. By the mid-eleventh century, there were no more than 5 Overseers in the whole of North Africa, 20 years later there were only 2. An Overseer was chosen at Hippo in 1074 but was sent to Rome by the Muslim governor. Three needed Overseers could not be found in Africa. By 1114 there was one Overseer in Bejaia, Algeria.

Christian communities still existed even up until the 12th century. There is evidence of religious pilgrimages after 850 AD until the eleventh century to the tombs of Christian saints outside Carthage. There was also evidence of contact with Christians in Muslim Spain. The Christian Berbers of Tunis had contact with Rome, as they were able to implement new calendar reforms not possible without said contact.

Norman Rule & last communities of Christian Berbers

The Christian reconquest of Africa began under the norman Roger II (king of Sicily) in 1146–48. His sicilian rule consisted of military garrisons in the major towns, exactions on the local Muslim population, protection of local (mostly berber) Christians and the minting of coin. The local aristocracy was largely left in place, and Muslim princes controlled the civil government under Sicilian oversight. Economic connections between Sicily and Africa, which were strong before the conquest, were strengthened, while ties between Africa and northern Italy were expanded.

So, in 1135–1160 a Norman kingdom of Africa existed in coastal Tunisia and the Christians there were protected. The Christian community, until then mostly servile and enslaved, benefited from Roger II's rule and even grew when some Italian Christians moved there. A new church was built in Mahdia, the first in the Maghreb since the Arab conquest. It is supposed that the episcopal 'See of Africa' was established by the catholic church when the city of Mahdia was held by the Kingdom of Sicily and when Pope Eugene III consecrated a bishop for it in 1148: the Christian bishop Cosmas of Mahdia went to Rome in 1145 and was officially confirmed by Pope Eugene III. He also visited his new sovereign in Palermo. Cosmas returned to Africa "a free man". But in 1156–1160 the Almohads reconquered the region.

The small Christian Berber community was attacked and practically disappeared. However, some small communities still existed in southern Tunisia and western Tripolitania until the beginning of the "Duecento" (XIII century). Only the small island of Tabarka in northern Tunisia remained in Christian hands until the beginning of the Renaissance, as it was the property of the Republic of Pisa.

Norman Kingdom of Africa (1135-1160) In the second half of the fifteenth century, the Roman humanist Paolo Pompilio noted the territory of Gafsa was populated by a land of small villages in which the inhabitants spoke a "Latinity". Berber Christians continued to live there until the 15th century, while they didn't recognize the new Catholicism of the Renaissance Roman Papacy. This would perhaps deny them support from other Christian powers.

In the first quarter of the fifteenth century, the native Christians of Tunis, even though they were heavily assimilated into Islam in various aspects, extended their church, as the last Christians from all over the Maghreb were gathered there. This is the last reference to native Christianity in North-West Africa; Tunis and Capsa seemed to be the last Christian citadels for over fourteen hundred years of continuous Christianity.

Indeed several families of the old African Church were found in Tunis when Charles V landed there in 1535. Leo the African thus describes the state of affairs in that city about this time: " In the suburb near the gate of El Mauera is a particular street, which is like another little suburb, in which dwell the ' Christians of Tunis.' They are employed as the guard of the Sultan and on some other special duties. In the suburb near the sea-gate, Bab-el-Baar (on the side of the Goulette), live the foreign Christian merchants, such as the Venetians, the Genoese, and the Catalans. There are all their shops and their own houses, separated from those of the Moors."

A most careful distinction was evidently drawn between the 'Christians of Tunis ' and the merchants from Europe. The former have their special quarters, as in eastern cities all nationalities do, but they are allowed to live near the Moors; on the other hand the merchants are necessary to the trade of the city and must therefore be tolerated; but they are kept as near the edge of the town and as far from their Mohammedan neighbours as possible. The ' Christians of Tunis ' were neither settlers from Europe nor renegades, but for the most part at any rate were the direct descendants of the great autochthonous African Church. They performed special and honourable duties, and were allowed to exercise their religion unmolested in a chapel of their own.

However their end soon came. In 1583 the Turks, long masters of Algiers, took Tunis and dethroned Mohammed, the last of the Aben-Hafis. The new conquerors were fanatical haters of Christianity, and all who refused to embrace Mohammedanism were in deadly peril from them. Their violence was chiefly directed against the native Christians, and while the foreigners were too useful or too well protected to be persecuted to death, the poor remnant of the African Church was forced to apostatize or die.

Consequently, native Berber Christianity was assimilated by force into Islam (read https://archive.org/stream/extinctionofchr00holm/extinctionofchr00holm_djvu.txt) and it died out all over the Maghreb under the Ottomans at the end of the XVI century, with the small exception of the surroundings of Ceuta (then called "Septem").

Furthermore, the Berber Christians of Roman Mauretania's Septem seem to have been assimilated into the Christianity of nearby Spain. Septem (actual Spain's Ceuta) was another pocket of Christianity left over from the Roman period. The episode of the martyrdom of Saint Daniele Fasanella and his Franciscans in 1227 AD, showed that Christians were still present in "Septa" (as it was known in Arabic); this Christian community remained on the outskirts of the city until the arrival of the Portuguese in the 15th century. Since then, the city -renamed Ceuta- has remained in Christian hands (Portuguese and Spanish), and now has a majority of the population speaking Spanish. The Berber Christians of Mauretania's Septem seem to have adopted Christianity with nearby Spain, and are considered the only survivors of the early Christian faith once native to Roman Africa, according to historian Robin Daniel (read http://www.tarifit.info/pdfbooks/thisholyseed.pdf ). This "miraculous" survival is due to the fact that Septem (actual Spanish Ceuta) was never conquered by the Turks, who fanatically exterminated the autochthonous Berber Christians when occupied the Maghreb in the late 1400s - early 1500s.

Reintroduction of Christianity

Christianity was finally made a mainstream religion when the Roman Catholic Church was reintroduced by the French following their conquest. The Diocese of Algiers was established in 1838. In 1685 some Protestants were already in Tunis, while the Vicariate apostolic of Tunis was reestablished in 1843.

Around 1930 there was again a huge community of Christian Berbers, but after decolonization they suffered persecutions and now the Maghreb has only around 1% of its population as Christians in the 2010s (also because of the return to France of the French "Pied-Noirs" after the 1962 Algeria independence).

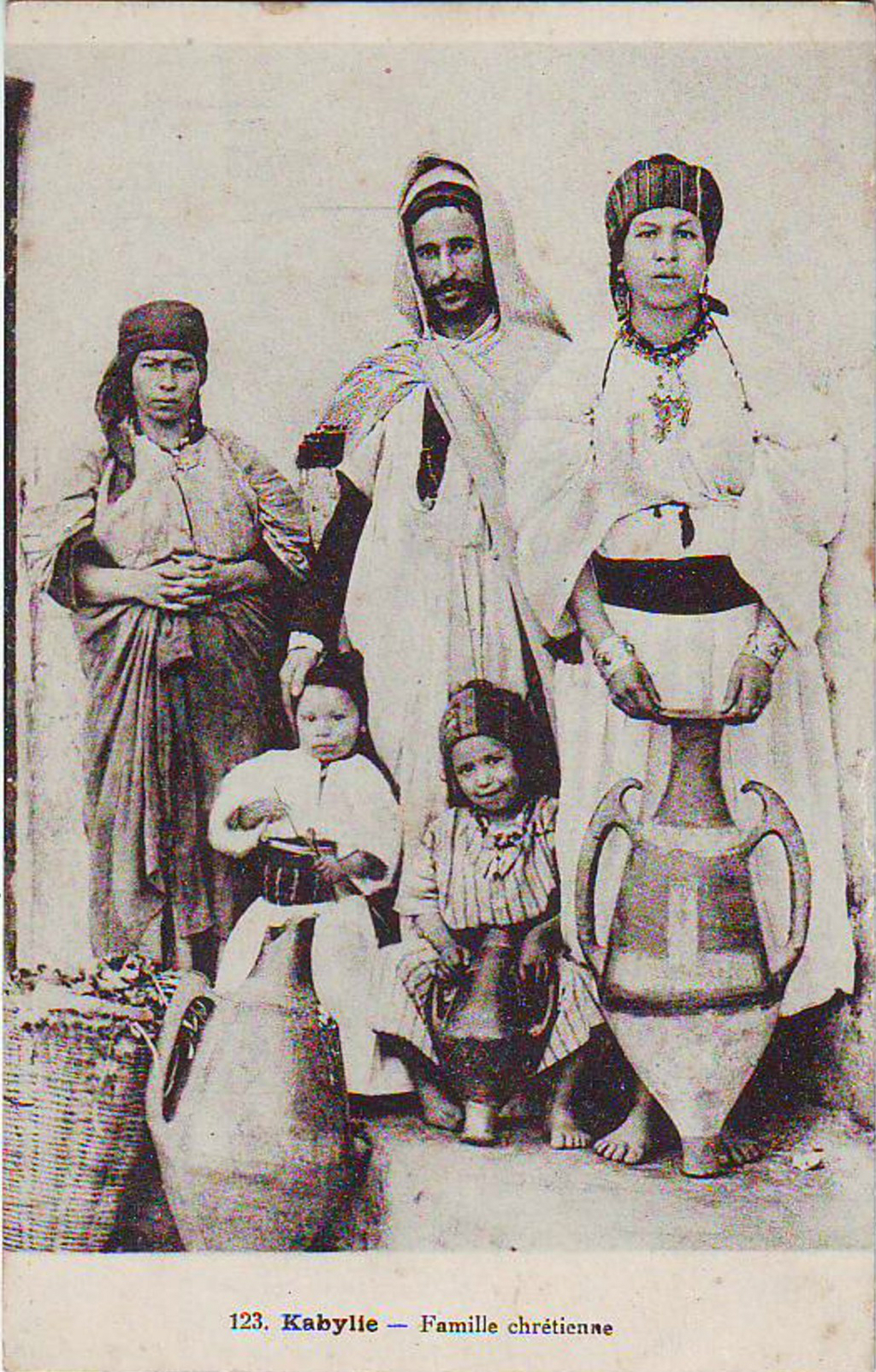

However Christian Berber minorities are actually making up to 5% of the population at most areas of 'Kabylie' in Algeria, where they are successfully growing: according to Duane Miller in 2025 there could be half a million Christians in Algeria (and nearly another 100,000 in the other countries of the "Berber Maghreb", from Mauretania to Libya).

Well known Christian Berbers in our times include Malika Oufkir, a Moroccan writer, daughter of General Mohamed Oufkir and "Brother Rachid" Hammami, a famous television personality in Morocco.

Actual situation

Actually, even after the Arab domination of the Maghreb since the eight century (interrupted only by the century of French colonialism), estimates show that there are more than half a million Christian Berbers, many living in a situation of diaspora in Western Europe and the Americas while nearly 350,000 living in the "Berber Maghreb" region of North Africa (from Mauretania & Morocco to Libya & western Egypt).

In 2009, the ONU counted in Algeria 45,000 Roman Catholics and 50,000 to 100,000 Protestants, mostly Berbers. Conversions to Christianity have been most common in Berber-populated Kabylie, especially in the wilaya of Tizi-Ouzou. In that wilaya, the proportion of Christians has been estimated to be more than 5%. Furthermore, some researchers estimate that in 2015 there were 380,000 Christians who are converted Muslims in Algeria (most of them Berbers: read https://www.academia.edu/16338087/Believers_in_Christ_from_a_Muslim_Background_A_Global_Census )

In Morocco the expatriate Christian community (Roman Catholic and Protestant) consists of 5,000 practicing members, although estimates of Christians residing in the country at any particular time range up to 25,000. Most Christians reside in the Casablanca, Tangier and Rabat urban areas. The majority of Christians in Morocco are foreigners, although 'Voice of the Martyrs' reports there is a growing number of native Moroccans (45,000) converting to Christianity, especially in the rural areas. Many of the converts are baptized secretly in Morocco’s churches inside the Berber communities.

The Christian community in Tunisia, composed of indigenous residents (mostly Tunisians of Italian and French colonial descent) and a large group of native-born citizens of Berber (and also Arab) descent, numbers more than 30,000 and is dispersed throughout the country. However one third of them lives in the capital metropolitan area.

In Libya there it is a small community of catholic Berbers in Tripolitania: it is numbering around two thousand persons, converted since Italian colonial times. It is concentrated in the Nafusah mountains (where autochthonous Berber Christianity survived until the 1300s; read https://books.google.com/books?id=pIkmvKB8OlsC&pg=PP1&dq=christians+of+Gef%C3%A0ra&source=gbs_selected_pages&cad=3#v=onepage&q=christians%20of%20Gef%C3%A0ra&f=false) and in the capital Tripoli's metropolitan area.

POST SCRIPTUM: After a few years, in the following December 2020 I wrote an article that is related to the above "Christian Berbers". If interested go to: https://researchomnia.blogspot.com/2020/12/christian-berbers-and-rome.html.