A brief account of Fascism & fascist movements in Latin America in the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s:

The question of Fascism in Latin America (including French Canada) dates back to the 1920s and 1930s. Certain fascist-type movements emerged in Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, Peru, Venezuela and Mexico, among others, while in Europe, Fascism was on the rise amidst an atmosphere of intellectual and political radicalism.

There was even a relatively small number of Italians in Latin America who were members of the "Italian Fascist Party", but this will be researched in another future monthly issue. And we must pinpoint that the Casa d'Italia (Italian House) Bulletin in Caracas wrote in 1939 that there were "Fascio all'Estero" in Caracas, Valencia, Puerto Cabello, Duaca, Santa Cruz de Mora (in the state of Mérida), San Cristóbal, Valera, and Villa de Cura (and that these organizations had more than 1000 members).

However it is noteworthy to pinpoint that the important fascist Giuseppe Bastianini in 1922 was appointed in Roma as head of the "Fasci Italiani all'Estero", a movement aimed at co-ordinating the activities of Italian fascists not currently living in Italy. He called on members to seek to diffuse proper Italian fascist ideals wherever they were living. This group gained a considerable following amongst Italian expatriates in the mid-1920s, mainly in South America. Indeed, in 1925 he submitted a report to the Fascist Grand Council claiming to have groups in 40 countries worldwide, most of them in Latin America.

However the Italian fascists had a partially negative opinion of the fascist movements that were arising in Latinoamerica (please read and google-translate from spanish: https://www.academia.edu/64653626/Fascismo_en_Am%C3%A9rica_Latina_La_Perspectiva_Italiana_1922_1943_?email_work_card=view-paper ). The only major movement recognized by the Italian fascists as "fascist" was the Brazilian Integralist Action (AIB). Diplomats, publications, the press, and Ciano all expressed this view. Everything else that appears fascist, however, was viewed with skepticism or rejected. The documentation of the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MAE) was particularly forceful in this regard. Similar fascist movements, or those reputed to be such, that emerged in many countries during the 1930s, such as the Argentine Fascist Party (1932), the National Socialist Movement of Chile (1932), and the Mexicanist Revolutionary Action (1934), aroused more pessimism than hope among Italian observers.

Another factor behind the development of forms of Italian Fascism in Latin America was the huge emigration of Italians in the region. Countries like Argentina had half of its population made of Italians and their descendants in the first half of the XX century.

We will now briefly review these movements in Latin America:

Argentina fascists in 1939: the "Fascio" of Buenos Aires had more than 4000 members. After the WW2 disappearance of Fascism, nearly all of them become fanatical supporters of Peronism

In 1922, the year Mussolini became prime minister of Italy, a reactionary and anti-communist group called "The Leopards" was founded in Colombia, inspired by the ideas of the Duce (nickname of Mussolini). In 1933, as Hitler consolidated his totalitarian regime, the "Golden Shirts" (called "Camisas Doradas" in Spanish) were founded in Mexico, an anti-Semitic and anti-Chinese movement inspired by the Führer's National Socialism. In Brazil, in 1932, the largest fascist group in Latin America, the Brazilian Integralist Action, was born, led by Plínio Salgado claimed as many as 200,000 member. In 1937 many thousands of Brasilian fascists militants used the Greek letter sigma (∑) as the equivalent of the Italian "Fascio" and united under the motto "God, Homeland, and Family."

Imitating the Nazis, Brazilian fascists raised their right arms in greeting. Unlike the Germans, they added something extra to the greeting: "Anauê!", an indigenous Tupi word meaning something similar to "you are my comrade". A short word to indicate that the Latin-American fascists were similar to their European friends, but not entirely the same.

Of course, the country in Latin-America where Fascism was more followed and powerful -because it was the most populated by Italians- was Argentina. Even Uruguay experienced a similar situation.

Argentina

In 1919, the "Argentine Patriotic League" emerged in Argentina during the presidency of Hipólito Irigoyen. This event coincided with the rise of Fascism in Italy. The Patriotic League had a nationalist program that combined right-wing politics and liberalism in economics. It enjoyed broad support from the government, the military, the Catholic Church, and the upper class, and formed civilian paramilitary squads called "White Guards" (similar to Mussolini's "Black Shirts") to suppress strikers, anarchists, Jews, and Catalans.

Vittorio Valdani, vice president of the Argentine Industrial Association, was charged by the Italian Fascist Party with organizing and directing Italian fascist groups in Argentina, creating in 1930 the main fascist press organ in South America, the newspaper "Il Mattino d'Italia", which was published in Italian language until October 1944.

"In order to disseminate the Fascist ideology abroad, different organizations were built up by Mussolini, most importantly the "Fasci italiani all’estero", which operated in many countries and had 8 million members worldwide. The local Fascio in Buenos Aires was the first to be founded on Latin American soil, even before the March on Rome in October 1922 and in the continental comparison also remained the most important. Further Fasci in other Argentine cities followed. Claiming the interpretative monopoly of italianità, which under fascism coincided with the Fascist ideology, the Fasci in Argentina tried to instigate patriotic sentiments and resuscitate emotional connections towards the former homeland among the otherwise ideologically heterogeneous Italian community in Argentina. Therefore, the Fasci engaged in the social, cultural and educational sphere, rivaling among others with the various traditional associations of Italian immigrants in Argentina, mostly of charitable, social or cultural nature. Katharina Schembs"

There were other fascist-type movements in the 1920s, such as the "Argentine Social League", whose objective was to fight modernism and tendencies they considered subversive. From 1930 to 1943 (the "infamous decade"), several dictatorships followed one another: Uriburo, Justo, Ortíz, and Castillo. In 1930, the coup-monger General Uriburo attempted to create a fascist regime, but failed due to opposition from broad sectors, including conservatives linked to the USA.

In 1923 was created the "National Fascist Party" (Partrido Nacional Fascista) of Argentina, a fascist political party that was directly linked to Mussolini. It had five thousand members in 1927 and was centered in Buenos Aires and Cordoba.

In 1932 the "Argentine Fascist Party" (Partido Fascista Argentino) was founded\ by Italo-argentines, as a split from one of the factions of the National Fascist Party. The PFA was founded on the ideological and doctrinal basis of Italian Fascism, and in fact in 1935 it was recognized by the Italian National Fascist Party. In the 1930s the party became a mass organization, especially in the city of Córdoba. Nicholas Vitelli led the Córdoba faction of the Argentine Fascist Party until his death in 1934, when Nimio de Anquín took the reins of the party leading it towards a new orientation close to Catholic nationalism,

The "National Fascist Union" (Union Nacional Fascista) was a fascist political party formed in Argentina in 1936, as the successor to the Argentine Fascist Party. It was dismantled during WW2.

Flag of the "Partido Fascista Argentino", created by the Italian-Argentine Nicola Vitelli

Between 1943 and 1946, the so-called United Officers Group ("GOU") took power and imposed a dictatorship. Its main leaders included high-ranking officers Farrell, Ávalos, Vernengo, and Colonel Juan Domingo Perón. Before Perón prevailed over this group of officers, who at one point conspired, imprisoned him, and forced his retirement, masses of mostly workers demanded his release on October 17, 1945, and later prevailed in the 1946 elections.

It's important to note that Peron publicly admired Mussolini. His support for Mussolini is well documented, and during a trip to Europe in 1938 he said:

"Italian Fascism made people's organizations participate more on the country's political stage. Before Mussolini's rise to power, the state was separated from the workers, and the former had no involvement in the latter."

Payne emphasizes the fascist characteristics of Peronism, especially the years Perón spent in power between 1946 and 1955, but not the subsequent history of the "Peronist Party" as a mass labor union movement. Several scholars of the early stages of the Peronist movement argue that it shared many characteristics of Italian Fascism.

Although Perón's goal was to found a single party, it was never achieved in practice. Peronism enjoyed strong support from the Union sector and was based on a limited authoritarianism that tolerated pluralism. Germani defined Peronism as a "national populism," adding a populist approach to the discussion. Lipset, on the other hand, classified it as "left-wing Fascism," highlighting that its largely union-based social base could shift from right to left.

Brazil

In Brazil, between 1932 and 1938, a movement with fascist influences emerged, the "Ação Integralista Brasileira" (Brazilian Integralist Action, AIB), founded by the writer Plinio Salgado. The AIB was inspired by an anti-parliamentary, traditionalist, and monarchist Portuguese movement, known as "Lusitanian Integralism". It was an important mass political movement that at one point had more than 500,000 members and met virtually all the conditions of a fascist organization. However, the ruler Getulio Vargas, after flirting with the movement, finally demobilized and banned it under US influence during WW2.

In Integralism, the attitude and production of its ideologues, its publications and propaganda, and its rigorously hierarchical structure tend to demonstrate its eminently fascist character, obviously in a different historical context. Integralism possesses characteristics of European fascist movements with certain indigenous elements, without being a simple replica of those movements.

In the Italian fascist organizations, both immigrants and their descendants were accepted, such as in the case of the "Fascio di Sao Paolo", one of the main organizations of Italian fascism in Brazil.

The Fascio di Sao Paolo was formed in March 1923 approximately 6 months after the fascists took power in Italy; it achieved huge success among the Italians of the city and rapidly spread to other cities and Italian communities. In November 1931, a branch of the Opera Nazionale Dopolavoro, which had existed in Italy since 1925, was founded in São Paulo and subsequently placed under the control of the Fascio di Sao Paulo. The Fascio was responsible for spreading the fascist doctrine among the popular classes.

Another institution at the time was the Circolo Italiano di Sao Paolo which was established in 1910 and still active today. Its aim has been to preserve and disseminate Italian culture to Italian-Brazilians and Brazilians in general. In the mid-1920s, the fascist doctrine began to infiltrate the community and institution through the influence of Serafino Mazzolini, the Italian consul to Brazil

In 1927, it was reported that many in Brazil "felt strongly Italian" and supported Mussolini. According to that 1927 report, Brazil had 52 fascist groups, and by 1934, this number had increased to 82. Of these, 35 were concentrated in São Paulo alone. By 1938, there were nearly 100 Fasci groups in the country

Brasilian integralist in a 1935 Sao Paulo manifestation doing the fascist salute

Regarding Vargas's government from 1930 to 1937, it fluctuated between the anti-oligarchic "dictatorship" (1930 to 1934) and the constitutional-liberal government from 1934 to 1937; in the next stage, before the election of his successor, he carried out a coup d'état with the support of the Armed Forces and imposed an authoritarian and repressive system ("Estado Novo", 1937 to 1945); finally, Vargas was elected President of the Republic by universal suffrage in 1950 through the Brazilian Labor Party.

Under his successor, he carried out a coup d'état with the support of the armed forces and imposed an authoritarian and repressive system (Estado Novo, 1937 to 1945). Finally, Vargas was elected President of the Republic in 1950 by universal suffrage through the Brazilian Labor Party.

Uruguay

In Uruguay, a group of far-right intellectuals and politicians took advantage of the 1929 depression and began to criticize the executive branch for its poor handling of the economic situation. The Uruguayan economic elite founded the "Vigilance Committee" with the intention of promoting a change in economic policies.

In Uruguay there was a huge Italian community (that was nearly one third of the total population of Uruguay) and the influence of Italian Fascism was very strong and important like in nearby Argentina (please read with google translation:.http://www.chasque.net/frontpage/relacion/9909/uruguay.htm).

Indeed elected President Gabriel Terra (an italo-uruguayan), who had already expressed fascist ideas, led a coup d'état and dissolved Parliament and the National Administrative Council in 1933. The "March on Montevideo" (similar to the March on Rome led by Mussolini) was called in support of him in April 1933.

Gabriel Terra's followers became known as "Marzists" due to their adherence to the "March Revolution," the official name of the coup. Elections were called for the Constituent Assembly that drafted the 1934 Constitution. The constitution, founded on corporatist principles, formally recognized the human rights to education, health care, and work, as well as freedom of assembly and association. Terra broke off diplomatic relations with the USSR and the Second Spanish Republic, recognizing Franco's Spain.

The "March regime" developed anti-immigration policies, such as controlling Jewish immigration and establishing a minimum of 80% Uruguayan labor in public works. Despite holding favorable opinions about the system, the 1934 Constituent Assembly rejected the full implementation of corporatism in Uruguay, considering it too radical.

Indeed during the Terra regime (1933-1938), several political leaders expressed their intentions to incorporate certain fascist premises into Uruguay. Gabriel Terra and César Charlone made no secret of their fascist sympathies. The latter emphasized the need to introduce corporatism into Uruguayan legislation, proposing "union pacts" and concepts of "the newest labor rights" taken from Mussolini's "Carta del Lavoro". These ideas were put into practice with the creation of the Higher Council of Labor in 1933, which required it to be composed of Unions that would enjoy legal status.

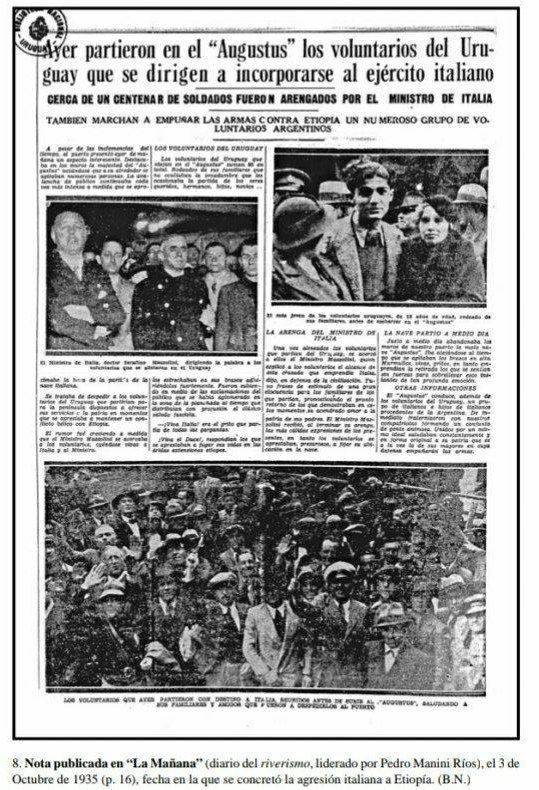

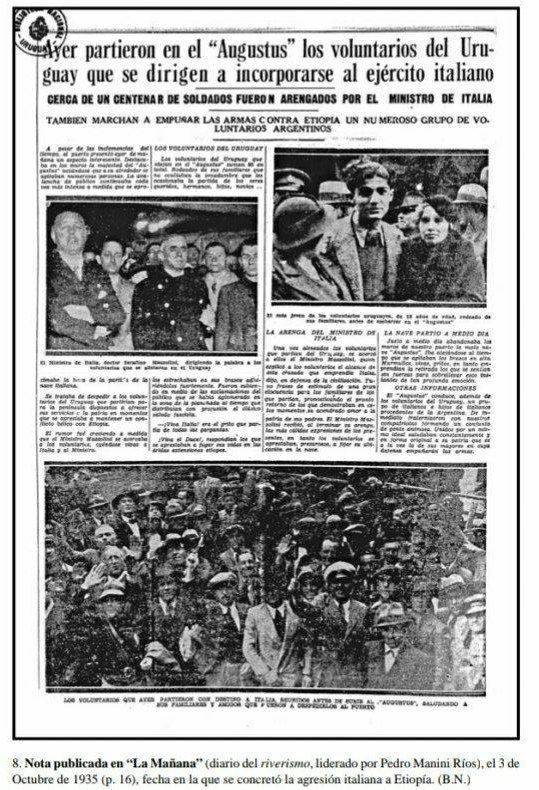

It is noteworthy to remember that president Terra allowed 100 Uruguayans to fight as volunteers in the Italian conquest of Ethiopia in October 1935. Terra was also the first south-american politician to recognize the Franco regime in Spain.

The Italian language acquired considerable importance in Uruguay in those years under Terra and his successors: in 1942, under the presidency of Baldomir Ferrari (who admired Italian Fascism), its study became compulsory in all the high schools of Uruguay.

Uruguayan newspaper showing the 100 Uruguayan volunteers who went to Ethiopia to fight for Mussolini's conquest of this African country in 1935. In the headlines there it is written: "Yesterday sailed in the Augustus (ship) the volunteers of Uruguay who go to unite to the Italian Army (in Ethiopia)...Nearly one hundred soldiers were enrolled by a Minister of Italy...Also, a huge group of volunteers from Argentina goes to fight Ethiopia with armaments "

Chile

The Fascist Party of Chile (PFC) was founded in 1932 by Carlos Keller. The PFC was inspired by Italian fascism and Spanish Falangism and promoted national unity, dictatorship, and corporatism. Unlike the MNS, the PFC had a more limited social base, composed primarily of intellectuals and members of the lower middle class.

Chilean fascism was characterized by its strong nationalism and authoritarianism. Fascist leaders emphasized the importance of Chile as a nation and the need for charismatic and authoritarian leadership to address the country's problems.

Chilean fascism championed corporatism, a system in which workers organized into their respective unions and participated in the management of the economy, and in which the antagonism between capital and labor was suppressed. Furthermore, Chilean fascism was openly anti-communist, which earned it the support of a significant segment of the Chilean population, who viewed communism as a threat to property and individual freedoms.

The Chilean Fascist Party participated in the 1938 presidential elections but was defeated by the Popular Front candidate, Pedro Aguirre Cerda. From that moment on, Chilean fascism lost ground and ceased to be a relevant political option in Chile.

Despite its short life, Chilean fascism left a lasting legacy in Chilean politics. The nationalist and authoritarian discourse it championed influenced the formation of later political groups, such as the National Union and the military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet. Furthermore, some historians argue that elements of Chilean fascism are present in contemporary Chilean politics, especially in the populist and authoritarian currents that have emerged in recent years.

Furthermore , in 1933 Chile, a movement emerged that aspired to adopt the principles of Nazism. The National Socialist Movement of Chile, or Nazi Party (MNS), was created. The MNS was configured with a hierarchical command structure, which was completed in 1933 with the "Nacist Assault Troops."

In 1938, before the elections, it organized a demonstration called "The Victory March." The following day, a group from the MNS took over the Workers' Insurance Fund and the University of Chile's main campus to launch a coup against President Arturo Alessandri and impose General Ibáñez on power. The coup failed, and the government ordered the execution of the insurgents.

In 1939, the MNS was renamed the Popular Socialist Vanguard (VPS), adopting a leftist stance, which caused most of its members to abandon the party, which dissolved in 1942.

Mexico

In Mexico, especially after the economic crisis of 1929, groups of ultranationalists, xenophobes, or racists emerged, among whom one was anti-Semitic and another anti-Chinese.

The "Revolutionary Mexicanist Action" (Spanish: Acción Revolucionaria Mexicanista), better known as the Gold Shirts (Camisas Doradas), was a Mexican fascist, anti-Semitic, anti-Chinese, anti-communist, ultra-nationalist paramilitary organization; it originated on March 10, 1934 in Mexico City and disbanded in 1936. It was led by Nicolas Carrasco, an admirer of Mussolini and Hitler.

The National Synarchist Union defended the values of Catholicism and anti-communism. It was inspired by the National Catholicism of the Spanish Falangist movement.

The Traditionalist Spanish Phalanx also emerged, gaining the support of Mexican President Lázaro Cárdenas, who facilitated the integration of Spanish Republican exiles into Mexico.

Peru

In Peru, the "Revolutionary Union" (RU) was created in 1931 by Sanchez Cerro, who admired Mussolini. In 1933, it was led by the Prime Minister of Peru -Luis A. Flores Medina- and became an openly fascist party that opposed liberalism and communism, and in particular the APRA party. They promoted xenophobia against Japanese and Chinese immigrants. They proposed a corporatist and totalitarian society similar to the model of European fascist movements of the interwar period.

Beginning in 1933 and after the murder of President of Peru Sanchez Cerro, the Revolutionary Union propagated a resoundingly fascist discourse similar to that used in Mussolini's Italy. At the end of 1933, the "Blackshirt Legion" was created, comprised of youth, following the authoritarian line. Furthermore, the RU promoted the rights of equality for women under the leadership of the Italo Peruvian Yolanda Coco Ferrero. She is considered one of the first feminist leaders in world History.

Indeed under the leadership of Luis A. Flores, who sought to mobilize mass support and even set up a Blackshirt movement in imitation of the Italian model (called "Camicie Nere" in Italy), the Revolutionary Union successively planned a coup d'état which was discovered in 1937, leading to Flores exile in Chile.

Flores was allowed to return to Peru in the early 1940s and reorganized his political fascist party, which never achieved the same results it reached in 1936 and disappeared with the final defeat of Fascism in 1945 WW2.

Photo of funeral for murdered President of Peru Sanchez Cerro in 1933, showing behind the priest the leader of the "Revolutionary Union" (RU) Luis Flores (dressed with fascist black shirt) and the Italo Peruvian feminist RU leader Yolanda Ferrero (who was the first to equalize woman rights in Peru).

Bolivia

The governments of David Toro and Germán Busch were vaguely committed to corporatism, ultra-nationalism, and national syndicalism, but they lacked coherence in their ideas. Such concepts were later adopted by the "Revolutionary Nationalist Movement" (MNR), which openly acknowledged its ideological debt to Fascism and joined the military under Gualberto Villarroel's pro-Axis government in 1943. But after WW2 the MNR moved away from the defeated Fascism.

Because historically the Bolivian army contained some German advisors and German-trained soldiers, the President Busch (of part-German ancestry himself) was suspected to have sympathy for Fascism and have Nazi tendencies; this was reinforced by the fact that only a week after taking power in 1937, he had requested economic and oil advisors from the German legation. On 9 April 1939, shortly before his declaration of dictatorial rule on the 24th, Busch had spoken with Ernst Wendler, the German minister in Bolivia, to request "moral and material support" for the establishment of "order and authority in the state through [...] the transition to a totalitarian state form". To do this, Busch asked for German advisors in almost every field of government administration.

While Wendler expressed interest, the final reply by the German government on 22 April cordially denied Busch's request, stating that it wished to avoid "conspicuous measures, such as the sending of a staff of advisors". The possible reason was the refusal of Bush to accept the racism of Hitler and accept the immigration of Jews into Bolivia while escaping from Europe in 1939.

Furthermore from an initially oppositional stance, Óscar Únzaga's "Bolivian Socialist Falange" was an important group in the 1930s that sought to incorporate the ideas of the leader of fascism in Spain, the falangist José Antonio Primo de Rivera, in Bolivia. However, like the MNR, it gradually de-emphasized its faith in Fascism over time after 1945.

Paraguay

Paraguay has been often declared as "The paradise of the extreme-right fanatics in South America", because the first Nazi party in the Americas was created there in 1929, 4 years before Hitler took power in Germany. The ideals of Fascism were promoted in the capital La Asuncion by the relatively huge Italian and German communities of the country during the 1920s and 1930s.

Indeed the "Febrerista movement", active during the second half of the1930s, demonstrated some support for Fascism by seeking revolutionary change, endorsing strong nationalism, and seeking to partly introduce corporatism of Italian Fascism. Their revolutionary Rafael Franco-led government, however, proved decidedly non-radical during its brief presidential tenure in 1936.

The Febreristas have since regrouped as the "Revolutionary Febrerista Party", that supported after WW2 the 35 years of the dictatorship of the Paraguay President Stroessner (a declared admirer of Mussolini's Fascism).

Ecuador

In Ecuador there was a small Italian community concentrated in Guayaquil (with nearly two thousand members), where was created an italian "Fascio" in 1933 with 82 members. However politically Fascism in Ecuador was without importance in the 1930s.

Only in 1942 Jorge Luna Yépes formed the "Accion Revolucionaria Nacionalista Ecuatoriana" (ARNE) party, inspired by the European fascist political parties of the first half of the 20th century, particularly the Spanish Falangism of Francisco Franco. His party described itself as "nationalist, anti-communist and anti-capitalist". During its existence it had an important political participation, both in the legislative and executive branches, being part of the government of Ecuador president José María Velasco Ibarra in 1944.

Panama

The Central American leader who came closest to being an important domestic fascist was Arturo Arias who in Panama during the 1940s, became a strong admirer and advocate of Italian Fascism, following his ascension to presidency in 1940.

Arias in the 1930s was Panama ambassador in Mussolini's Italy and this fact led some historians to claim he was pro-Axis. During his presidency he created the "Doctrina Panamista" promoting independence from the USA and some forms of fascist corporativism. As a consequence he was forced to resign by a coup (probably ruled by Roosevelt) and go in exile in October 1941.

Costa Rica

In Costa Rica there was a big community of Italians (nearly half a million descendants actually) and also a relatively huge of Germans, mainly in the San Jose capital's region.

The existence of figures who were sympathetic to Fascism and Nazism in high

political positions has been pointed out in the administrations of León Cortés Castro and Rafael Ángel Calderón Guardia.

Cortés, having spent some time in Italy and Nazi Germany, was publicly viewed as an important sympathizer of Mussolini's Fascism. He was President fro 1936 to 1940 and during his presidency, he appointed as "immigration advisor" the German-Costarican Max Effinger, who restricted

immigration for "Non-Aryans". In particular, he prevented many Polish

Jewish refugees from entering Costa Rica

In the late 1930s, a movement which was sympathetic to Nazism developed among a large community of Germans. Supporters of Nazism (numbering 66 in 1939) met in a local German Club of San Jose, but during WW2 all Germans and Italians were sent to concentration camps for security reasons promoted by the USA .

Quebec (French Canada)

Among the right-wing nationalists in French Canada

in the 1930s, the "National Social Christian Party" (NSCP) was founded.

Its founder, Adrien Arcand, would be known as the “Canadian Duce/Fuhrer.”

European influence,

anti-Semitism, Christianism, and the Great Depression all played an

important role in the expansion of extremist right-wing nationalism in

Quebec. There were two main groups among the nationalists of the extreme

right in the 1930s: the separatist group of Abbé Lionel Groulx, and the

federalist group of Adrien Arcand.

Groulx was an historian and a

teacher at the University of Montreal. Pro-separatist, Catholic, racist,

and anti-democracy, he was very influential among his fellow

ultranationalists. Groulx was the mentor of the radical nationalist

group Les Jeune Canada (“The Young Canadians”). Also linked to his circle was the magazine L’Action Nationale and intellectual newspaper Le Devoir, which published anti-Semitic articles.

Adrien Arcand was a professional journalist. In 1929, he and his friend Joseph Ménard started Le Goglu, a satirical review. Later on, they added Le Miroir and Le Chameau.

The three weekly newspapers served as a platform for fascist propaganda.

When the economic crisis started to strongly affect Quebec, they

announced the creation of a “proto-fascist” movement called the "Ordre Patriotique des Goglus". The Order held mass meetings promoting racism and proudly wore blue shirts with swastika logos.

Pierre Trudeau -when young- was sympathetic with Fascism and promoted the French language as official in Quebec (French Canada) when was Prime Minister of Canada after WW2.

Recently the academic Esther Delisle wrote that Pierre Trudeau (Prime Minister of Canada and creator of bilingualism in French Canada) was sympathetic with Fascism, when was a young university student. She wrote that "In his memoirs, Trudeau remains mute on the anti-liberal and anti-democratic ideology of many of his Jesuit teachers at the college Jean-de-Brébeuf. He also fails to mention the support for Fascism and Nazism in Le Quartier latin, his membership of Les Frères Chasseurs/LX and the Bloc Universitaire and his deep attachment to La Laurentie that lasted into adulthood"). Please read:https://journals.uclpress.co.uk/ljcs/article/id/3154/ "Hidden in Plain sight: Fascism in Quebec during the Second World War", by Esther Delisle.

With WW2 all the fascist organizations in Quebec were outlawed and closed.

Colombia

The fascist-style politics of the conservatism of the "Leopardos" would be closely linked to the actions of the different elements of Colombian conservatism at the beginning of the 20th century.

These different ideological orientations would begin their career as fascist-style cultural and economic movements, eventually revealing their true purpose and minimally achieving their political goals and projects. They imitated practices of the fascist models that would triumph in Europe, such as those of Italy, but also of Germany and Spain.

The year 1936 saw the proliferation of Fascist and Falangist groups. In January, El Tiempo of Bogotá announced the creation of a fascist group called "Haz de Fuego" (Fire Beam) and the appointment of the Falangists from the "Primo de Rivera" center as its leader. Fascist groups were formed in Bogotá's universities. In Medellín, a military organization called "La Cruz de Malta" (The Cross of Malta) and another group with a clearly fascist character called "Haz de Juventudes Godas" (God Youth Beam) appeared. Under the auspices of the Antioquia's "Haz Godo" (God Youth Beam) were created, several phalanxes of university students, workers, "rearguard of children," and also a phalanx of women.

Some right-wingers promoted the formation of a right-wing organization separate from the Conservative Party, structured around a program directly inspired by Hitler, Mussolini, and Oliveira Salazar.

This led to the emergence of various support organizations for these fascist models, influenced by the results and support obtained as a political movement before WW2.

Venezuela

Dictator Gomez from 1908 until 1935 ruled Venezuela with a "colonial" dictatorship that had only a few fascist characteristics, mostly related to Germany's racism. He favored the "Blanqueamiento" (whitening) of the Venezuelan population, blocking the immigration of Chinese, Asian & African people into oil-rich Venezuela and promoting the creation of the Nazi party of Venezuela.

The Italo venezuelan Alberto Adriani, who was the creator of the famous "Sembrar el petroleo" phrase when was minister of Economy & Finance in 1936 Venezuela, in 1923 wrote:

"Fascism is not a passing episode. It has its roots in the purest Latin and Italian tradition. The fascist state is the Roman state that the Church maintained in its ironclad organization; the same state as Machiavelli's "The Prince." Despite the diversity of starting points, the same results are reached as with liberalism. For Fascism, the nation is paramount; it accepts freedom from a national perspective; it desires equality, but focuses on possibilities; it wants, if possible, to turn the entire country into a vast aristocracy, but it refuses to destroy the elite to place everyone at the level of the least" A.Adriani (please read for complete info: https://albertoadriani.substack.com/p/liga-de-naciones-y-fascismo).

In 1939 there was an Italian "Fascio" in Venezuela with more than one thousand Italian members, of which 200 were in the capital Caracas: this fascist organization was ordered to be closed in 1941, following political pressures from USA's president Roosevelt (please read https://lombardinelmondo.org/italiani-venezuela-fascismo/ with google translator from Italian language).

The renowned writer and key figure of the literary "Magical Realism" movement of Venezuela, Arturo Uslar Pietri (whose mother was Italian), held pro-Axis and anti-US sentiments, attempting to sway President Medina Angarita towards aligning with Germany and Italy during the beginning of WW2. Subsequently, Pietri went on to serve as a senator and establish the Nationalist party known as the National Democratic Front (Frente Nacional Democrático).

A noteworthy detail of fascist Venezuelans is that Ettore Chimeri, recognized as the first Venezuelan to compete in Formula 1, was a member of Squadron 73 in the Royal Italian Aeronautics during World War II, serving in the African campaign.

Enrique Parra Bozo, who was noted for his admiration of Franco & Mussolini as well as his Catholicism and anti-communism, led the Partido Auténtico Nacionalista along Fascist lines. The group lent its support in the 1950s to the military regime of Perez Jimenez and even attempted, though unsuccessfully, to nominate him as their candidate for the 1963 presidential election.

Conclusions:

In short, there is no doubt that during the 1920s and 1930s, fascist models emerged in Latin America that mimicked Italian, German, or Spanish Fascism, in some cases a minority, such as "Nacism" in Chile, or broad and well-rooted movements such as "Integralism" in Brazil or "Marzism" in Uruguay, clearly founded on European interwar Fascism.

However, in no case were these truly consolidated fascist regimes. The Italian fascist government always "separated" himself from these movements and created a fascist organization only for Italians residents in Latin America & the World: the "Fascio degli Italiani all'Estero" (the "Fascism of Italians in the World"). It promoted mainly the italianita' (italianity) in Latin America, while obtained only the official use of the Italian language in Uruguay's schools and the participation of hundreds of Argentine & Uruguayan volunteers in the Italian army (during the Italian conquest of Ethiopia).

The case of Peronism is special, because presents native complexities as it is a populist movement with fascist features, based on Trade Unions, which has a broad mass base, and which brings it closer to a left-wing Fascism, but accepting pluralism at first to a greater extent and then to a lesser extent, as it shifted toward repression in its final stage.

The Second World War sealed, in a certain sense, the fate of the Fascism overseas in Latin America. Patriotic pride of Italy was followed by the humiliation of defeat. But the fascists did not disappear, nor did they lose prestige. Nor did the corporatist ideology, anti-Americanism, distrust of democracy, and the cult of the leader that these Italians and their descendants had professed disappear, and which merged with other ideologies in the rhetoric and practice of subsequent populisms (like Peronism in Argentina).

Juan Domingo Perón (in the photo center), President of Argentina from 1946 to 1955 and from 1973 to 1974, admired Italian Fascism and, according to some authors, modeled his economic policies on those followed by fascist Italy.

Latin America dictatorships and Fascism until the 1970s.

Some academics identify a group of dictatorships in Latin America with Fascism:

According to them, the first dictatorships in Latin America classified as fascist were those imposed in the Dominican Republic by Rafael Trujillo, giving rise to "Trujillismo" (1930–1961), in El Salvador by Maximiliano Hernández Martínez, giving rise to the "Martinato" (1931–1944), and in Nicaragua by General Anastasio Somoza, giving rise to what is known as "Somocismo" (1937–1979).

All three imposed types of state without the possibility of political opposition, which extended over several decades, with the support of the United States and the economic elites, characterized by an ideology with a marked anti-communist accent, profoundly liberal in economics, and repressive of union, student, indigenous movements, and politicians with social justice programs.

The first dictatorship in Argentina also dates from that early period, explicitly -according to them- inspired by Italian Fascism, led by General José Félix Uriburu (1930-1932), whose aim was to prevent the Yrigoyenist Radicalism, with its broad popular base, from governing the country, an objective which it achieved although it did not manage to consolidate its hold on power.

Furthermore, certain dictatorships sparked a widespread debate about whether or not they constituted fascist regimes after WW2

In this group, we include the coups d'état in Brazil (1964), Uruguay (1973), Chile (1973), and Argentina (1976). Many scholars questioned how similar or different they were to the dictatorships of historical interwar fascism.

In Venezuela the dictatorship of Perez Jimenez (that had some characteristics of a moderate Fascism) lasted from 1952 until 1958 and promoted the "Europeization" of the country allowing nearly one million emigrants from Europe to reside in Venezuela (that had only 5 million inhabitants in the early1950s).

In 1959 took control of Cuba the communist leader Fidel Castro, who in his youth was an admirer of Mussolini, according to one of his teachers at the Colegio Belén, the Jesuit priest Armando Llorente.

According to Tzeiman, the 1960s, following the impetus of the Cuban Revolution, witnessed a growing intensification of class struggle in various parts of Latin America, whether through national-popular or socialist political movements. This climate of radicalization spread throughout the early 1970s. The military coup that took place in Chile in 1973 initiated a wave of dictatorships that would spread to other Latin American nations.

Thus, by the end of the 1970s, the southern cone of Latin America was invaded by military dictatorships whose establishment acted as a brake on the aforementioned popular advance. Cueva paints a bleak picture of the 1970s. Brazil's military dictatorship seemed fully consolidated after twelve years. In Bolivia, the Banzer dictatorship seemed to have imposed a stable pro-imperialist order. Uruguay and Chile were suffering the effects of the fascist regimes established since 1973; while in Argentina, the government of Mrs.Estela Martínez de Perón was dying, giving way to the dictatorship of General Videla. And in Uruguay, the Stroessner tyranny had remained unshaken in power since 1954.

In 1971, Nicos Poulantzas, who studied the processes of fascistization, examined these processes, concluding that, amidst the imperialist phase and class struggle, Fascism arose from a political and ideological crisis of the ruling group that generated a new hegemony of monopoly and financial capital. It is a political reaction to reinvent itself as a hegemonic power.

In other words, this bourgeoisie, in the midst of a crisis, "changes its clothes" and presents itself to the masses as the "solution," which includes elements such as order, corporatism, nationalism, and stability. Its displacement culminates in the obliteration of the opposition and the emergence of a fascist police state.

According to O'Donell, some of the inherited characteristics of historical Fascisms in Latin America are: hierarchical social organization, political exclusion, repression of the popular Marxist sector, suppression of foreign citizenship and participation, reconsideration and defense of the nation, violent elimination of dissent, patriotic and militarized discourse, promotion of Catholicism with Latin History & Culture links and -of course- sympathy for European Fascisms (mainly the Italian).

1936 photo showing in Roma the "Legion of Italians emigrants" (Legione Italiani all'Estero) parading in front of Mussolini (who was saluting them), after their return from conquering Ethiopia. Nearly all these "Legionaries" were volunteers Italians and Italian descendants from Argentina, Brasil, USA, Paraguay, Chile and Uruguay.

SM95BBomber.jpg)