I have written in May & June of this year about the end of the "Africa Orientale Italia" (A.O.I.) in the last months of 1941. But the end of this Italian East Africa empire was followed by a guerrilla war done by thousands of Italian soldiers with hundreds of Eritrean colonial troops (faithful to Italy). Indeed after the surrender of the last AOI Vicerroy (general Nasi) in Gondar and all the massacres and lootings that were done by the Ethiopian troops (mainly by the fanatical "Arbegnochs) that started to massacre also the local Italian civilians, looting everything (please read and "google translate" from italian: https://arcadia.sba.uniroma3.it/bitstream/2307/4213/1/Tesi%20di%20dottorato%20di%20Antonio%20Cataldi%202013.pdf I missionari cattolici in Etiopia; pag. 337-343), many Italian soldiers decided to continue to fight by themselves.

1941 photo of Amedeo Guillet -nicknamed "Devil commander"- giving orders to his cavalry Ascari. He attacked in that year a British unit of armored vehicles & tanks with his cavalry (that was armed only with guns, hand-grenades and knifes) and a British lieutenant wrote: "... When our battery took up position, a group of native cavalries, led by an officer on a white horse, charged from the north, rushing down from the hills. With exceptional courage these soldiers galloped to within thirty meters of our guns, firing from their saddles and throwing hand grenades, while our guns, turned 180 degrees, fired point-blank. The grenades slid along the ground without exploding, while some even tore open the chests of the horses. But before this charge of madmen could be stopped, our men had to resort to machine guns...."

.Most estimates (like the one of Rosselli, Alberto: "Storie Segrete. Operazioni sconosciute o dimenticate della seconda guerra mondiale") pinpoint that more than seven thousand Italians participated in this guerrilla, until the surrender of the Kingdom of Italy to the Allies on September 8, 1943. They fought in the desperate hope that the Italian & German Army of Rommel could win the war in Libya & Egypt and reach later the region of former AOI.

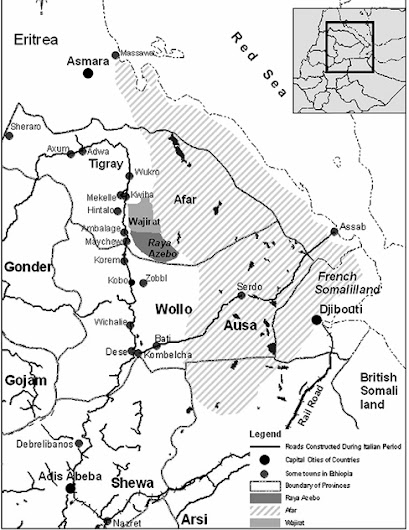

According to the italian historian LoPiccolo, some Italian officers continued to fight the English when the Fascist empire was already lost. Major Lucchetti, creator of the "Resistance Front" ("Fronte di Resistenza") in Addis Abeba, was one of them. Several “bands” joined his military organization. Members of this Front were the Carabinieri Captain Leopoldo Rizzo, the Grenadier Major Enrico Arisi, the Majors Giuseppe De Maria and Mario Bajon. Many bands organized rebellions against the authority of the Negus, as happened in Cobbò (Eritrea) with the Azebò Galla tribe. A rebellion that lasted for more than a year until 1943.

In other areas of south-western Ethiopia, such as Caffa and Gimma, acts of sabotage were organized. In Eritrea, in the Amba Auda region, a Royal Navy headquarters communicated with the "Maristat" (Navy General Staff) in Rome. Also in Eritrea, a clandestine cell was organized that took care of Italian soldiers who had escaped from prison and carried out acts of sabotage. It was led by the naval captain Paolo Aloisi and by a fascist militia officer, Luigi Cristiani. The latter had been captured and sentenced to death by the English. He avoided the sentence thanks to the intervention of the bishop of Asmara.

All these officers, non-commissioned officers and soldiers, contrary to what British intelligence had declared, were not “desperate” fighters without plans, but men experienced in sabotage actions. The guerrilla actions conducted between April 1941 and May 1943 involved all the regions included between Ethiopia, Sudan, Kenya, Dancalia and the Red Sea. The best equipped Italian units had model 91 rifles, Beretta pistols and Breda submachine guns. The effectiveness of their actions forced the English to ask for reinforcements supported by air and mechanized vehicles from Kenya and Sudan.

In February 1942, a revolt of the Galla Azebò broke out in the Galla Sidama region (Ethiopia) with the support of Italian units stationed in the desert areas and led by the militia general Muratori. The revolt lasted until 1943, when it was suppressed by British and Ethiopian troops. Other guerrilla actions were carried out in the area of the Omo-Bottego river (Ethiopia), at the beginning of 1942, where the group commanded by the Carabinieri lieutenant colonel Calderari attacked South African units. Similarly in Ogaden and Dancalia, where groups of Italian soldiers, including men from the fascist "MVSN" (Voluntary Militia for National Security), gave the English a hard time with various ambushes.

It seems that even in May 1942 Negus Haile Selassie intended (probably worried about the initial successes of the Italian-German forces in Egypt and Libya, of the German armies in the USSR and of the Japanese successes in the Far East) to start negotiations with the Italian “resistance” groups.

When the Axis troops were defeated at El Alamein in the autumn of 1942, causing a rapid occupation of Egypt and from there a hypothetical advance in the Middle East to vanish, the Italian “armed” groups began to face reality. Isolated in a territory difficult to tackle and without any more connections with the mother country, they began to abandon the idea of a now unequal fight. Only the “Resistance Front”, commanded by Major Lucchetti, continued to fight in an organised way, in the hope of a change in the situation. But his would be an illusion, because he was arrested by the British military authorities some days after the Italian-German lost of Libia in December 1942.

This desperate guerrilla war received no help from Italy: only the Italian air force dropped some needed military materials & did some attacks. For example: on May 1943 an Italian long range SM.75 bomber intended to attack an American airfield at Gura in Eritrea, but having encountered fuel difficulties was forced instead to bomb Port Sudan, causing huge damage.... however another Italian airplane was able to drop bombs on Gura.

"......In 1943, two SM.75 GA aircraft undertook a bombing mission, the only one made by an SM.75, intended to destroy American bombers stored at an airbase in Gura. To reach the objective, which was over 3,000 kilometers (1,900 mi) away, the two SM.75 were laden heavily with 11,000 kilograms (24,000 pounds) of fuel, and modified by fitting a "Jozza" bomb-aiming system and a bomb bay capable of carrying 1,200 kilograms (2,600 pounds) of bombs. The most experienced crews were selected for the mission, led by officers named Villa and Peroli. The mission started at 06:30 hours on 23 May 1943 from Rhodes, the easternmost Regia Aeronautica base at the time. The SM.75 GA's engines were optimized for endurance and economy rather than for power, which made the takeoff difficult with the heavy load of fuel and bombs. Initially flying at low altitude, at 10:00 hours the modified SM.75 GAs climbed to 3,000 meters (9,800 feet). Having used an excessive amount of fuel, Peroli diverted to bomb Port Sudan instead; he returned safely to Rhodes at 05:30 hours on 24 May 1943 after 23 hours in the air. Villa, meanwhile, pressed on alone and arrived over the Gura airbase—which was heavily defended despite being well behind the front line—at 18:45 hours and released his bombs....." BD.

It is interesting to note that last Italian guerrilla fighter to surrender was Corrado Turchetti, who wrote in his memoirs that some soldiers continued to ambush Allied troops until the end of October 1943.

Indeed, the last Italian troops to surrender were Eritrean colonial Ascari under the command of the "Muntaz" Ali Gabrè, an Eritrean "Zaptié" (Eritrean Carabinieri). In 1941, when the Italian Army surrendered to the English, he continued to fight and his resistance lasted until the beginning of 1946.

This means that, for five years, Ali Gabrè, known as "Ali Muntaz", with initially 8 other Eritrean & Italian soldiers, in the fort of Agordat area bravely opposed the English in the name of the King of Italy and he later continued on his own, with a hundred other "Eritrean Ascari diehards", to fight in the Abyssinian/Eritrean bush during all 1944 & 1945. He fought until the imbalance of forces and the lack of armaments forced them to lower the Italian tricolor flag, but only nearly one year after the end of WW2.

Thanks to these Italian & Eritrean fighters the Italian flag was present in Ethiopia from 1935 until 1946 (11 years) and not only less than five years (from 1936 to 1941), as it is written mistakenly by the actual Ethiopian propaganda! Some Ethiopians want to minimize the Italian colonial control on their country, but real History cannot be erased.....

1950 photo of the doctor Rosa Dainelli, secret agent of the Italian "Military Information Sevice" (Servizio Informazioni Militare) who participated in the Italian guerrilla war in Ethiopia (https://www.storiaverita.org/2023/10/06/rosa-dainelli-la-spia-sabotatrice-di-cuveglio-che-durante-la-seconda-guerra-mondiale-fece-impazzire-gli-inglesi-in-africa-orientale/)- Lieutenant Amedeo Guillet in Eritrea and northern Ethiopia

- Captain Francesco De Martini in Eritrea, northern Somalia & Ethiopia

- Naval Captain Paolo Aloisi in Eritrea

- Captain Leopoldo Rizzo in Ethiopia

- Colonel Di Marco in Ogaden of Somalia

- Colonel Ruglio in Eritrea

- General (black shirt) Muratori in Ethiopia & Eritrea

- Officer (black shirt) De Varda in Ethiopia

- Officer (black shirt) Luigi Cristiani in Eritrea

- Major Lucchetti in Ethiopia

- Major Gobbi in Ethiopia

- Colonel Nino Tramonti in Eritrea

- Colonel Calderari in Somalia

| |||

| |||

."...Already two months before the surrender of Gondar (November 27, 1941), the last Italian stronghold in East Africa defended by the brave and skilled General Nasi, that is, at the beginning of September 1941, several members of the fascist militia and the army decided to give life to a clandestine movement of revolt to oppose the British occupation forces and the new government of the Negus and to create the conditions for a reconquest, by the Italian-German Army of Africa of General Erwin Rommel, of Ethiopia, Eritrea and Somalia. The rapid and brilliant successes achieved in Cyrenaica by the German general in the months of February, March and April of 1941, induced many Italians in East Africa, both military and civilian, to hope for a possible "liberation" of the former Empire, even though the latter was now almost entirely under the control of the English and Ethiopian forces loyal to the Negus. As mentioned, already on 6 September, some elements from the ranks of the fascist party gave life to the secret Association Sons of Italy which, in addition to the fight against the occupiers of Albion, also proposed a "harsh repression against traitors, collaborators, profiteers, anti-fascists and anti-monarchists who had dishonoured the Fatherland". The association even managed to send a letter to Rome (to Mussolini himself) informing him of the existence and operation of "a resistance movement faithful to the fascist creed".

Almost at the same time as the establishment of the Sons of Italy Association, the Resistance Front was born in Addis Ababa, a military organization constituted and directed by Major Lucchetti and whose objective was to coordinate the guerrilla actions that several hundred Italian soldiers and civilians had been conducting since April 1941, shortly after the fall of the last great bastion of Cheren. Quantifying the exact numerical consistency and evaluating the equipment and armament of the numerous bands that went to flow into the organization (some report a total of at least 7,000 men, including officers, non-commissioned officers, soldiers and rearmed civilians) is not an easy thing, even if the testimonies, although contradictory as in all these cases, are not lacking. We know exactly the names of the 40 members of the first secret committee of the Resistance Front (among others, the captain of the Carabinieri Leopoldo Rizzo, the major of the grenadiers Enrico Arisi, the majors Giuseppe De Maria and Mario Bajon, the journalist F.G. Piccinni, the former vice-mayor of Addis Ababa Tavazza and other officers) and we know for sure the areas in which the gangs, even those not affiliated with the "Resistance Front" (such as the legendary one made up of the Amhara horsemen of the cavalry lieutenant Amedeo Guillet, who for several months in Eritrea gave the English a hard time).

In the region of Dessiè, the gang of Major Gobbi operated; while in Cobbò some officers organized the revolt of the Azebò Galla tribe hostile to the Negus. There were also armed gangs of saboteurs in Caffa and Gimma, and others active in the areas of Dembidollo, Moggio and Cercèr. And again, in the region of Amba Auda, near Saganeiti, a group of naval officers had managed to install a radio transmitter with which to send messages to the Maristat in Rome, while in Eritrea the captain of the vessel Paolo Aloisi and the senior of the fascist militia Luigi Cristiani had organized an assistance network for the soldiers who had escaped from the English concentration camps and a group of saboteurs. Captured by the English, the senior Cristiani was sentenced to death but escaped the capital punishment thanks to the intercession of the bishop of Asmara, Marinoni. In short, the Italian Resistance in East Africa was not the work of a few "desperate" people without plans (as was propagandized by those responsible for the British Secret Services), but was a phenomenon that involved a significant number of qualified individuals, command experts and accustomed to weapons and espionage and sabotage operations. For two years, from April 1941 to May 1943, the Italian units incorporated into the "partisan" bands fought a hard, obscure but often effective war against the English and Ethiopian units in a vast region between Sudan and Kenya, between the Red Sea and the Lakes region. The most organized Italian gangs had individual armament consisting of Beretta pistols, Model '91 muskets, Breda machine guns, Fiat and Schwarzlose machine guns, English war booty rifles, hand grenades, dynamite charges and even some 65 mm mountain pack animals, even though they were short of ammunition.

Some resistance units could also count on a certain number of camels, mules and horses for the transport of food, ammunition and equipment. After an initial phase of interlocution and organization (from spring to winter 1941, the bands operated mainly in the English rear, attacking isolated motorized columns and attacking small garrisons poorly defended by irregular Ethiopian troops), in 1942 the Italian units began to strike the enemy with greater precision, both in urban areas and in the countryside. So much so that the English Command was forced to recall from Kenya and Sudan some colored battalions supported by air and mechanized vehicles. The fear of a more widespread "Italian" revolt in East Africa had become more real following the successes obtained by the German Afrika Korps in Libya and Egypt and the entry into the war of Japan (7 December 1941) alongside Germany and Italy. In May 1942, following frequent sightings of large Japanese ocean-going submarines, equipped with small catapulted reconnaissance seaplanes, along the coasts of Yemen, Somalia, Tanzania and the northern part of Madagascar, the British Supreme Command strengthened surveillance of the African coasts of the Indian Ocean. And at the same time imprisoned or removed from cities such as Mogadishu, Kismayo and Dante almost all of the Italian settlers, fearing that some of them might provide useful information on the size (in truth rather small) of the British forces to the crews of the Japanese submarines.

From January 1942, a good percentage of the Italian units operating in the Ambe, in the desert areas or in the depths of the forests of south-west Ethiopia began to receive instructions from the secret command of the Militia General Muratori who, thanks to his strong influence on the Galla Azebò, had managed to start a revolt in the Galla Sidama region: a revolt that was suppressed by the British forces and only ended in 1943. Also at the beginning of '42, in the remote basin of the Omo Bottego-Baccano river, the band of Lieutenant Colonel Calderari of the Carabinieri put the small South African garrisons in serious difficulty, while those of Colonels Di Marco and Ruglio (operating, respectively, in the arid regions of Ogaden and Dancalia) and that of the Centurion of the Volunteer Militia for National Security De Varda (formed mainly by "black shirts") carried out several ambushes against enemy motorized columns, creating confusion and forcing the the British to strengthen surveillance along the truck roads and the most popular trails. In May 1942, Emperor Haile Selassie himself began to consider a "separate peace" with the Italians and even a form of underground collaboration in an anti-British function. After his new installation on 6 April 1941, by London, the Negus had had the opportunity to note the distrust and condescension with which he was treated by the plenipotentiaries of London: an attitude that he deplored to the point of considering a sensational about-face.

And it was precisely between May and July 1942 that the Negus, certainly impressed by Rommel's successes in North Africa, thought of this solution, intensifying, albeit with the utmost caution, contacts with the Italian "rebels" in Ethiopia. However, as the months passed and, despite brilliant coups carried out (but always kept quiet by the British media), the Italian bands began to lose that motivation in the fight that had supported them for so many months. Isolated from the mother country and forced to survive in very difficult territories from an environmental and climatic point of view, several units began to complain of dangerous weaknesses. In the late summer of 1942, after the definitive arrest of Rommel's Afrika Korps at El Alamein and the first serious setback suffered by the Japanese fleet in the Pacific at Midway, the hopes of being reached by the Axis armies faded. Throughout the winter and spring of 1942, word had spread among the resistance forces of East Africa of the imminent arrival, along the Nile, of a powerful and mythical "Italian-German relief column coming from Libya, with tanks, artillery and no less than 6,000 camels". A dream destined, however, to be shattered by the harsh and adverse reality.

n any case, on the eve of the "miracle", Major Lucchetti, still at the head of the Resistance Front, tried to reassure his units and even intensified his work "organizing special units of saboteurs, setting aside food and vehicles, and collecting money, in this last undertaking ably assisted by Monsignor Ossola, Catholic bishop of Harar".

Arrested by the English in October 1942, Lucchetti disappeared from the scene when, with Rommel's defeat in Egypt and with the almost total evacuation or imprisonment of soldiers and civilians from East Africa, any further resistance lost its meaning". "Our dreams of that time - recalls the "guerrilla" Corrado Turchetti in his memoirs - were not yet without hope. The Italian motorized forces, if they had succeeded in breaking the British defenses of El Alamein, could have returned down the Nile" and overwhelmed the English and Ethiopian armed forces that occupied the former Empire. The last effective guerrilla actions conducted by the Italians against the British occupation troops took place in that "historic" summer of '42 and were led by two truly exceptional characters: Dr. Rosa Dainelli and the captain of the SIM (Military Information Service) Francesco De Martini. After the death of Captain Bellia and Lieutenant Paoletti, who fell into an enemy ambush at the end of a series of sabotage actions, De Martini, who had already made himself known in '41 for some daring and brilliant actions in Dancalia, was taken prisoner (in July '41) but managed to escape and subsequently set fire to the ammunition depots of Daga (Massawa) with makeshift means.

De Martini, despite being hunted by the English police, created a network of informants in a few weeks (partly composed of Eritreans loyal to Italy) managing to send, via a makeshift radio, very useful information to the Command in Rome. It even seems that De Martini had managed to arm some Arab dhows with machine guns with which he carried out night missions to locate and report British naval convoys in transit along the Eritrean coast. De Martini survived (like the aforementioned Lieutenant Guillet, who narrowly escaped captivity and took refuge on a small boat in Yemen) the war and was decorated with the Gold Medal for Valor. And speaking of medals, a very special one would have rightfully gone to the courageous and fascinating doctor Rosa Dainelli who in August 1942, demonstrating patriotism, athleticism and uncommon courage, penetrated at night into the most guarded English ammunition depot in Addis Ababa, blowing it up with a dangerous charge of dynamite with a fuse. Rosa Dainelli miraculously managed to get away with it and, above all, to save her skin by causing the enemy much greater damage than she had foreseen. In the depot, in fact, there were 2 million special Fiocchi cartridges, booty of war that the English Command had already earmarked as ammunition for the new Sten machine guns that had just entered service but were still without an adequate supply of cartridges.

The failure to use Italian bullets forced the English to do without modern machine guns until November 1942 when the new purpose-built cartridges finally came out of the English factories. Towards the end of 1942, almost all the Italian armed bands began, as has been said, to disband and even the secret organizations that had followers and supporters among the inhabitants of the main Eritrean cities entered a phase of organizational collapse. And in the first months of 1943, the last national groups, hidden in the wildest regions of the Empire, laid down their weapons, but not before having made them unusable by the enemy. Thus ended, without any fanfare, one of the most interesting and least known pages of the Second World War......"

Finally,I want to add a translation from an Italian blog about the last guerrilla fighters of Ali Gabre, who fought for the Kingdom of Italy until spring 1946:

"Italy also had its "last Japanese", or rather over a hundred.

Yes, a unit of those glorious fighters who were the Eritrean Ascari surrendered only in 1946, when it actually had certainty that Italy had surrendered and the war was over. One hundred forgotten heroes (like many others) commanded by a courageous Sciumbasci, Alì Gabre.

As it is known, a tenacious Italian guerrilla continued to fight against the English even after the fall of Gondar (November 1941). The most famous Italian official of this guerrilla was Commander Guillet.

But very few know that apart from Guillet and other Italian officers in command of colonial units organized into "Bands", other units of loyal Ascari, left without Italian officers, continued to fight for the Motherland as long as they could.

The most tenacious unit was precisely the one commanded by Ali Gebre and composed of about 100 Eritrean mounted guerrillas. Among the other resistance groups, it is worth mentioning the one in which Amid Awate fought, considered the moral Father of modern independent Eritrea.

Gebre's band continued the guerrilla warfare as long as it could, ignoring the events that had occurred in the meantime in Italy, such as September 8 and April 25. Moreover, operating by necessity in a hostile territory characterized by large spaces, the band had to necessarily find shelter in the most remote and inaccessible areas of the AOI, therefore far from the areas inhabited by nationals and large cities such as Asmara, Massua or Addis Ababa. Therefore far from reliable sources of information, that is, Italian. Needless to say, having no intention of surrendering, the messages sent by the English regarding the armistice and then the surrender of Italy were totally ignored and considered deceptive (just like what happened to the last Japanese in the jungles).

But in the end, after yet another sabotage of the telegraph wires by the gang, in the late spring of 1946 the English command decided to charge former Italian officers of the Eritrean battalions, just liberated by virtue, rather than the peace conference underway in Paris, with the very task of going to the areas still "infested" by their former subordinates. Wearing their colonial uniform for the last time, the now former Italian officers had to communicate to them (documents in hand, just in case) that it was now time to surrender. Not without some difficulty did the Italian envoys manage to reach Ali Gebre's men, who, anxious to have news from Italy and convinced that these officers brought who knows what positive news, discovered instead that the war was lost, but also that they should be proud of having done much more than their duty."

Historian Luigi M. Rubino wrote in 2022 that no other European colonial power has had some of the own colonial soldiers fight for the Homeland like did the Ascari of Ali Gabre for Italy. And this unbelievable fight shows that Italy behaved in a very civilized way in Eritrea with the native population, without any superiority behavior or despicable real racism.

1941 photo of MVSN Italian militia in AOI